When we think of the Indian Independence movement, the first figures that jump to our minds are those of Gandhi, Nehru, and Bose. Larger national movements led by the Congress dominate our imaginations. The resolutions passed and the speeches given on the national stage against colonial rule is what we study in our textbooks. What gets lost in this conventional telling of the Indian Independence movement is the contribution by everyday Indians to the National movement. It’s their resistance against colonial rule that allowed the larger national movements succeed.

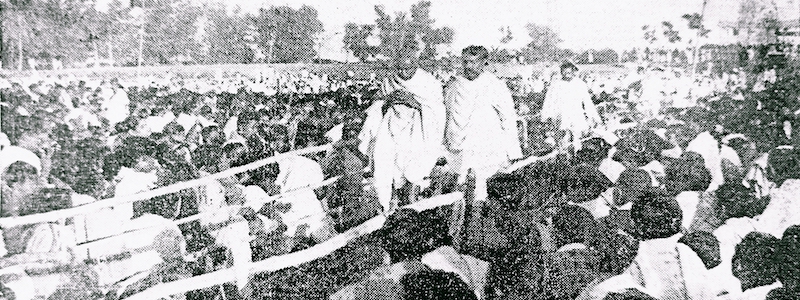

The Indian History Collective today brings you a remarkable story through archival documents of the time. A tale of common people in two sub-districts of Midnapore who fought against inhumane treatment by the British in the wake of the Bengal Famine. They threw out the British administration and set up a parallel government in 1942. This government called itself the Tamralipta Jatiya Sarkar or the Community government of Tamralipta.

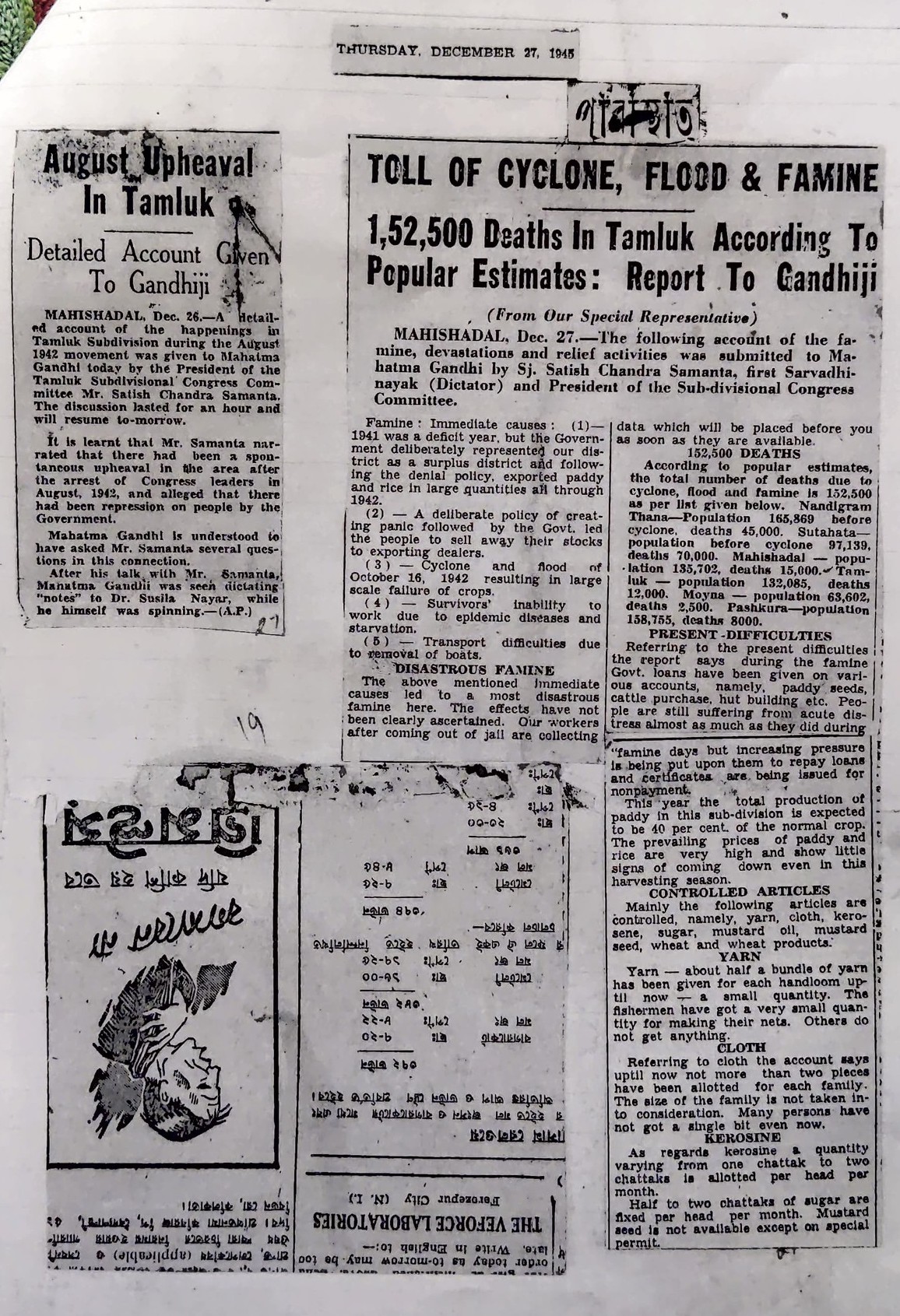

The Sarkar had its own army, intellgence services, courts, ran schools, amongst other functions. It was run by a Sarbadhinayak or dictator aided by Sachivas or ministers. It formed under the ideological backdrop of the Quit India Movement movement, however, as discussed above, the more urgent catalyst that spurred it’s formation was the inhumane treatment by the British Indian authorities. The sufferings of the people were added onto by a freak cyclone and a tidal wave that hit the district. The death toll was truly shocking. According to popular estimates of time, 1,52,500 out of a total district population of 7,52,283 died. Within the district, in Nandigram thana itself, 45,000 died out of a total population of 165,869.

The British Indian government treated the people of Midnapore with deliberate apathy as well as repression due to their involvement in the Quit India movement. Pradyot Kumar Maity in his book ‘Quit India Movement in Bengal and the Tamralipta Jatiya Sarkar’ writes: “The apathetic British Government took no steps to relieve the woes of the famine-stricken people fighting for freedom. Even the government did not allow private organisations to do the relief work for a pretty long time at Tamluk and Contai sub-divisions. Further the government deliberately delayed to air the news of the havoc caused on 16th October. The reason was to crush the anti-British movement which took a serious character in comparison with other places of India”

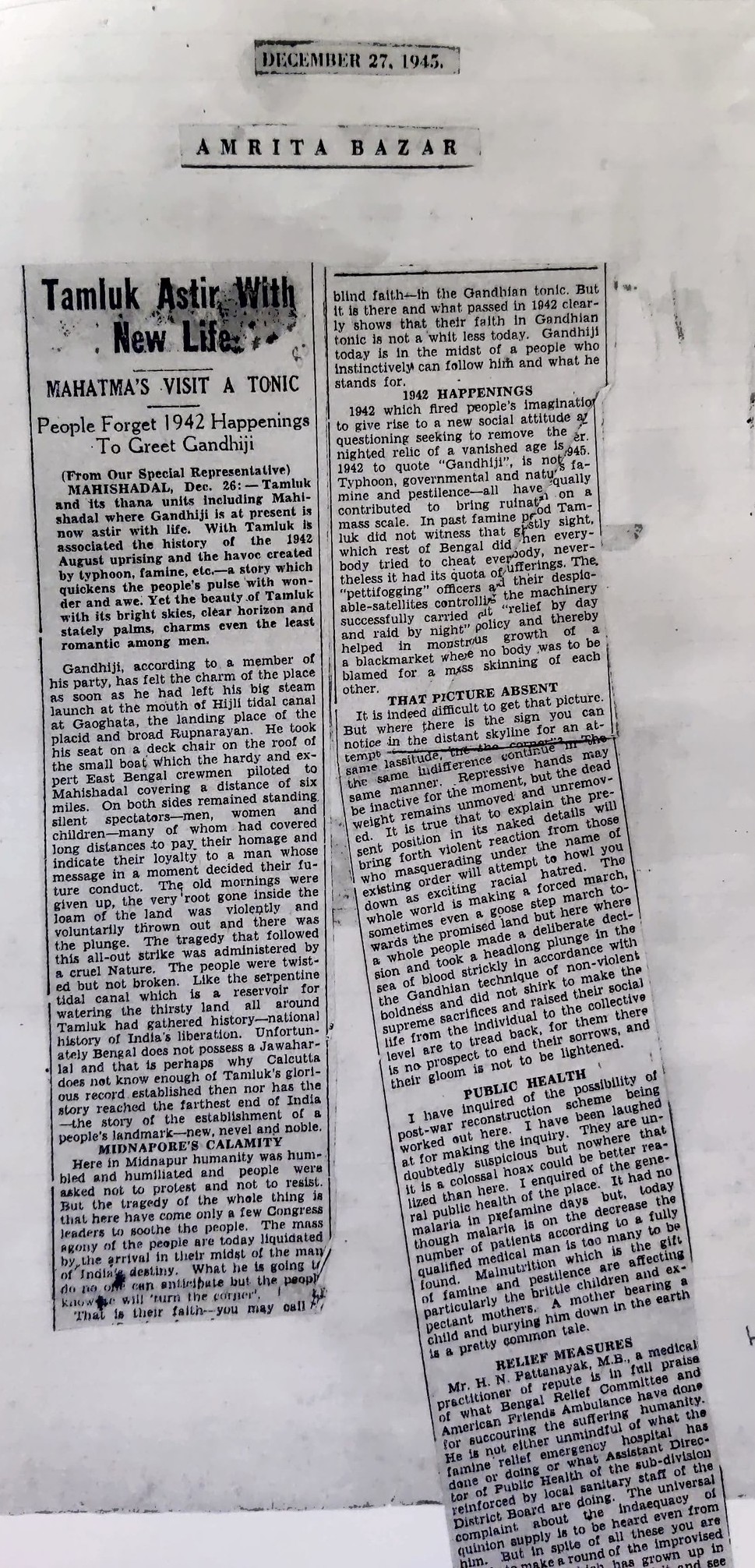

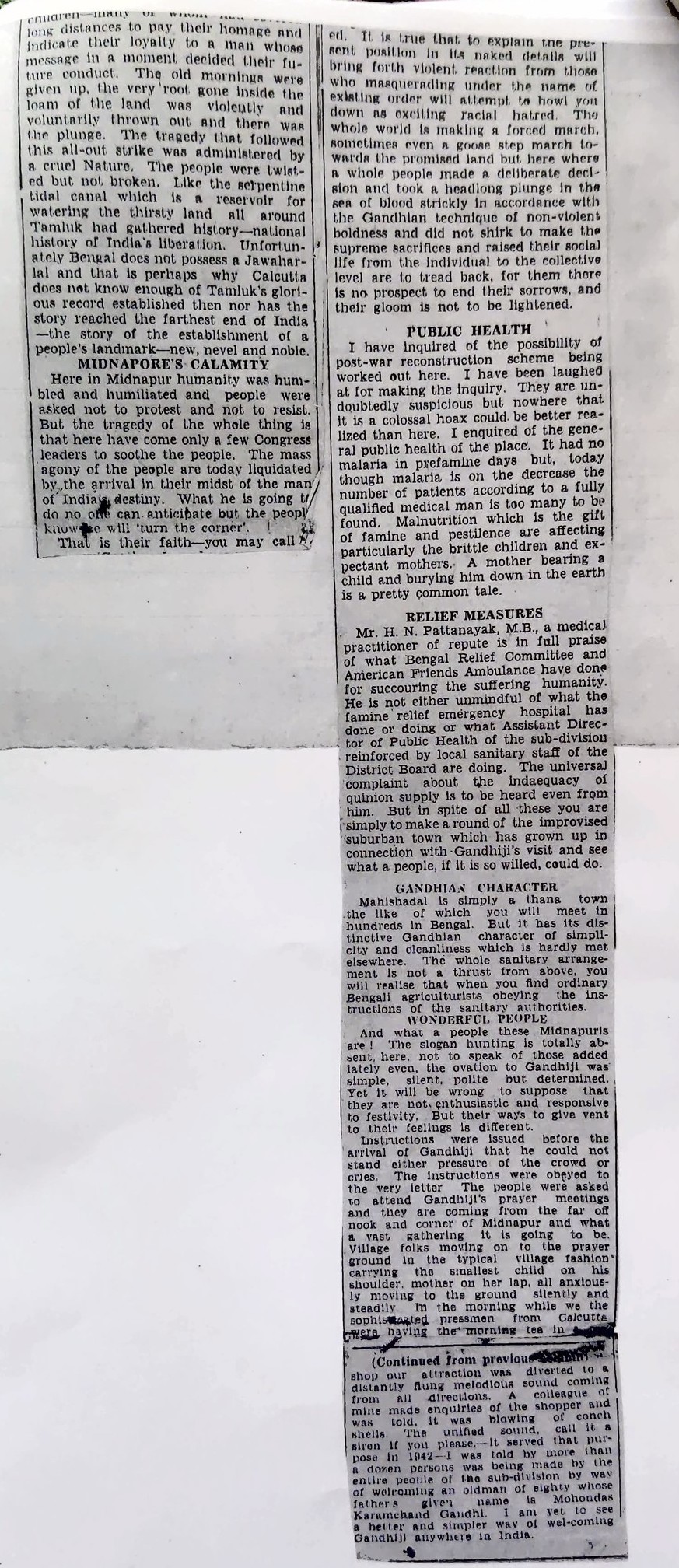

The Tamralipta Jatiya Sarkar ended its operations as a parallel government on 31st August, 1944, under Gandhi’s directive. This remarkable revolutionary movement left without making much of a mark on the national consciousness. Even as it ended its operations in 1945, the movement had not been highlighted by the National media. In one reporter’s words “Unfortunately, Bengal does not possess a Jawaharlal and that is perhaps why Calcutta does not know enough of Tamluk’s glorious record established then nor has the story reached the farthest end of India – the story of the establishment of a people’s landmark – new, novel and noble” The story was covered prominently only after Gandhi visited the affected regions post WW2 in December, 1945.

So why was this story not known more widely and why do we only know of it now? To answer the latter first, the archival documents that we highlight today were only collected by concerted local efforts of the Tamralipta Swadhinta Sangram Itihas Committee and deposited at the Prime Minister’s Library (formerly Nehru Memorial Library) only in the 1980s.

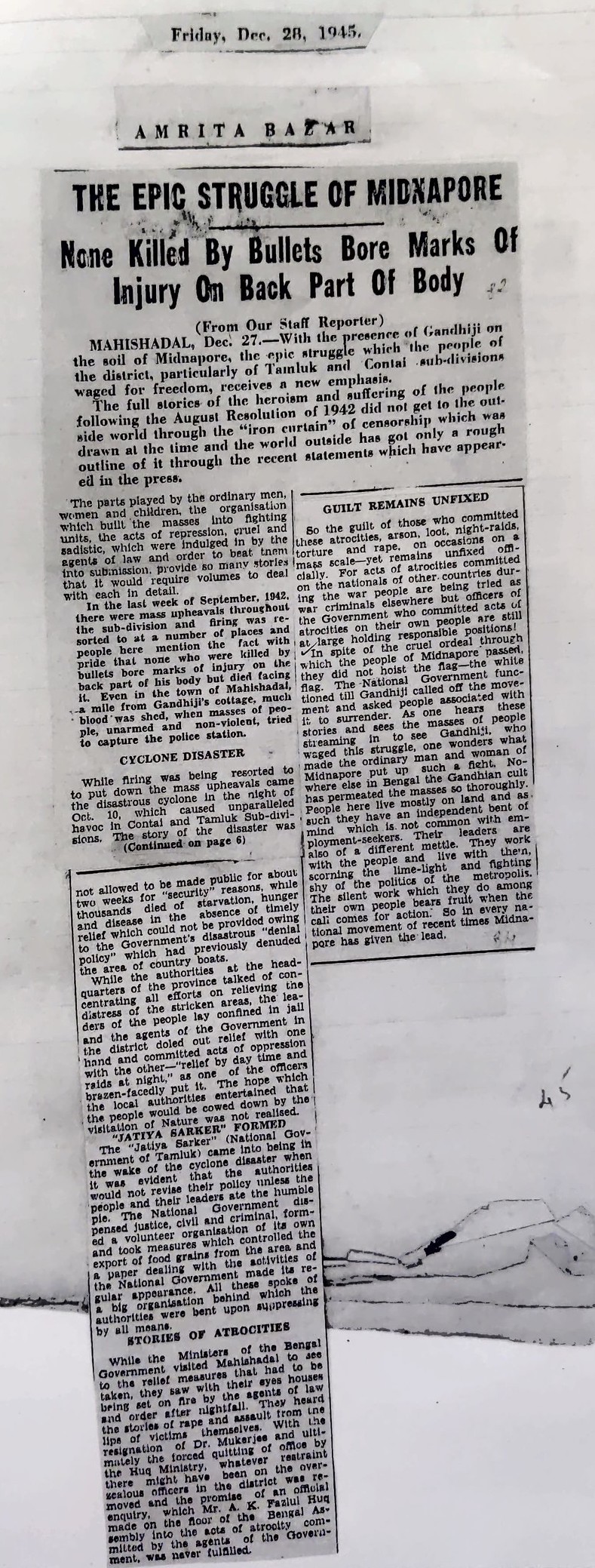

Another significant reason might be that wartime censorship laws prevented this movement from being highlighted at the time. As quoted in Dr. Devika Sethi’s – War over Words; one of the chief objectives of Wartime censorship in British India was to ‘prevent public opinion from being stirred to enthusiasm for the [anti-colonial] movement or to indignation against the Government’. One of the newspaper reports attached below references this reason; “The full stories of the heroism and suffering of the people following the August Revolution of 1942 did not get to the outside world through the “iron curtain” of censorship which was drawn at the time and the world outside has got only a rough outline of it through recent statement which have appeared in the press”

We are bringing this story to you in two parts through archival documents from the Prime Ministers Library (formerly Nehru Memorial Library). Part 1 of our story highlighted, the condition of the district in the aftermath of the flood, cyclone and tidal wave; the formation of the Sarkar’s War Council or ‘Bidyut Bahini’; Syama Prasad Mukherjee’s letters of protest and resignation against British mistreatment of the district to the chief minister of Bengal provincial government; the structure and functioning of the ‘Mahabharata Juktarashtra – Tamralipta Jatiya Sarkar’ and lastly the Role of Women in the revolution and in the functioning of the Sarkar.

This second part features newspaper reports covering Gandhi’s visit to the region, judicial documents highlighting the justice system under the Sarkar, and a series of letters written by now-unknown members of the revolutionary movement during the period of the Sarkar.

The newspapers are organised chronologically by date of publication. The judicial papers relate to one case and the personal letters are arranged in the order that the translator translated each one.

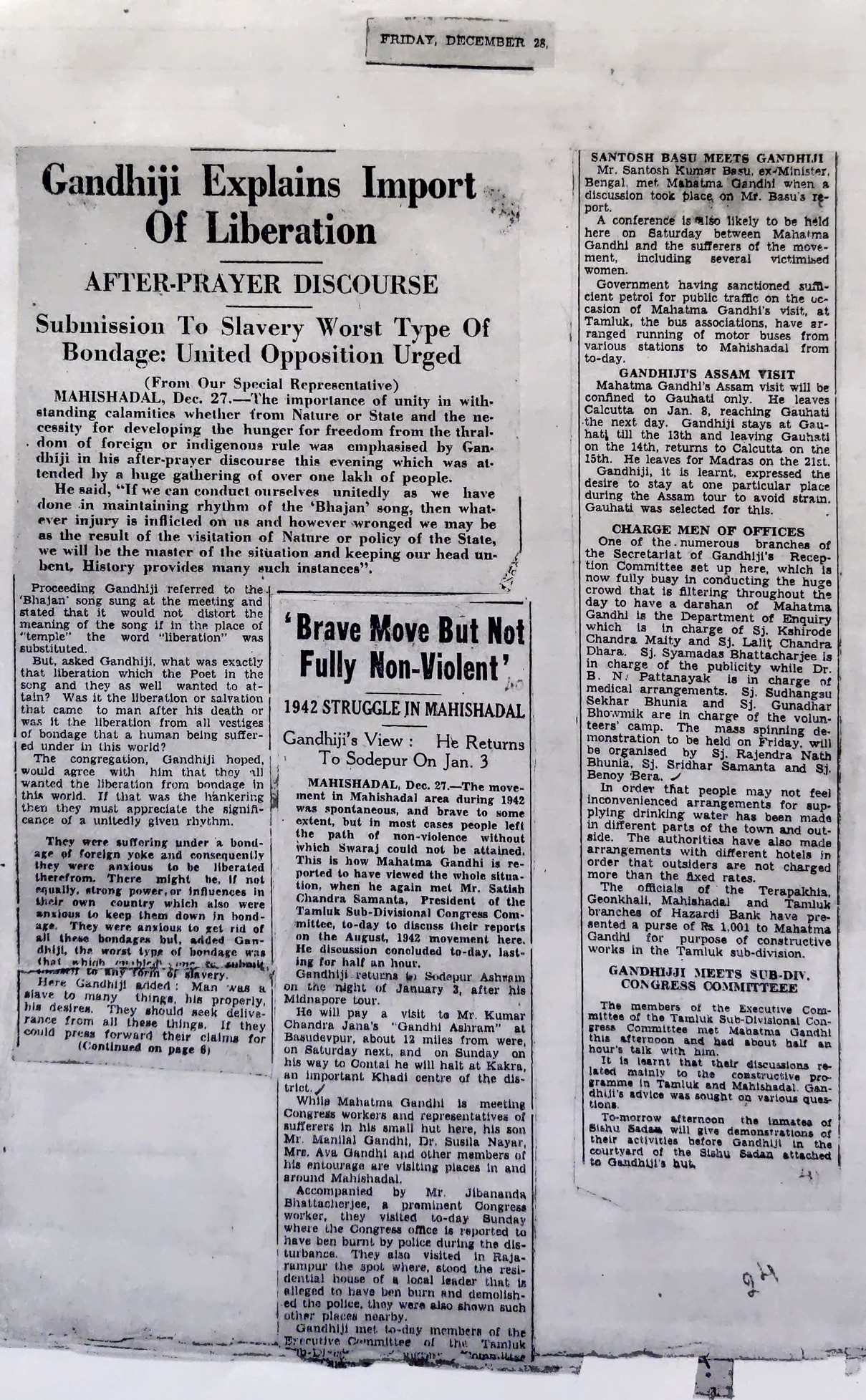

Despite our best efforts, we will not be able to convey the full story here, as the reporter of Amrita Bazar described on Dec 28, 1945 “The parts played by the ordinary men, women, and children, the organisation which built the masses into fighting units, the acts of repression, cruel and sadistic, which were indulged in by the agents of law and order to beat them into submission, provide so many stories that it would require volumes to deal with each in detail.”

Image 1

Image 2

Image 3

Image 4

Image 5

Image 6

An excerpt from the news column above:

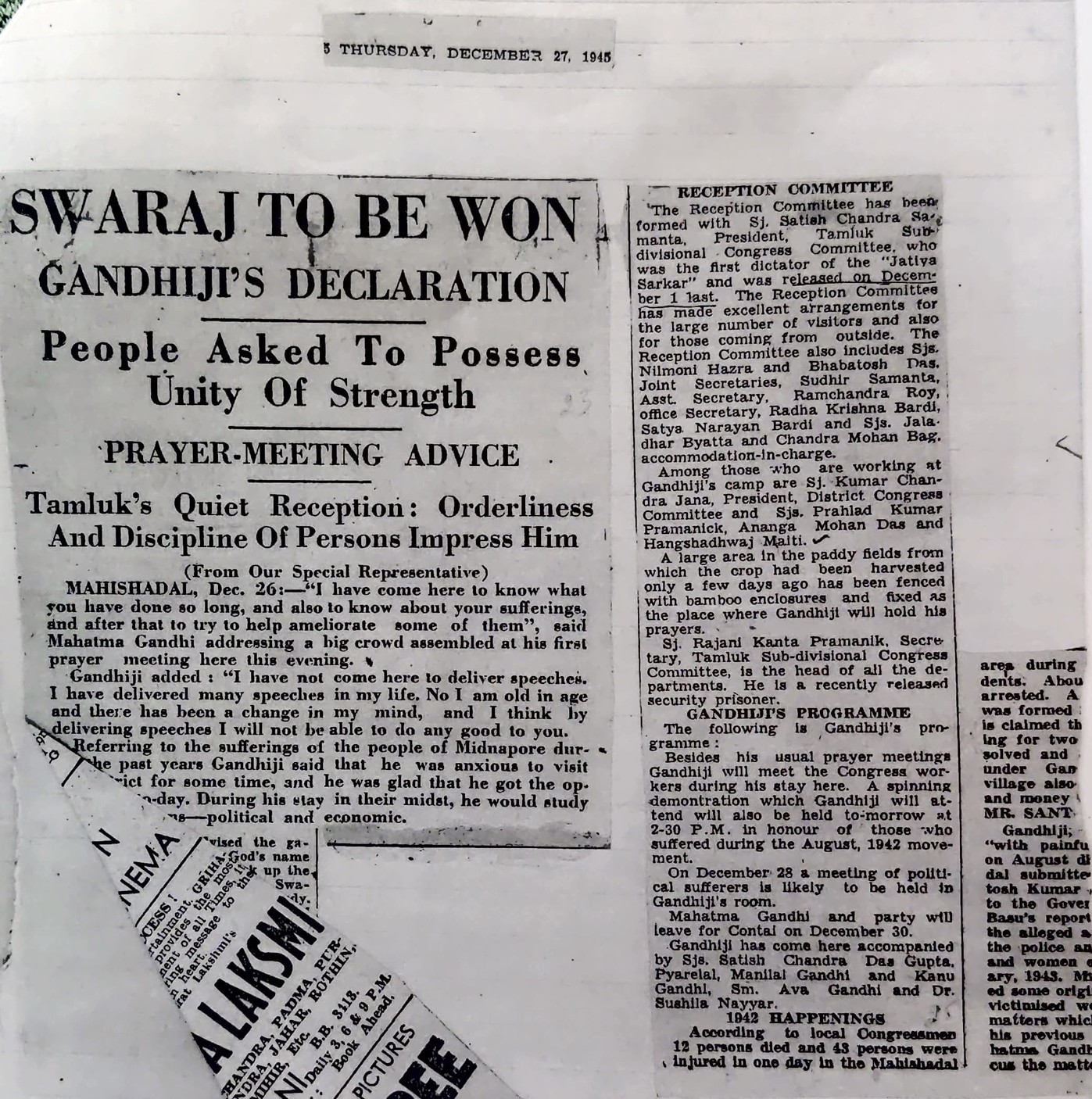

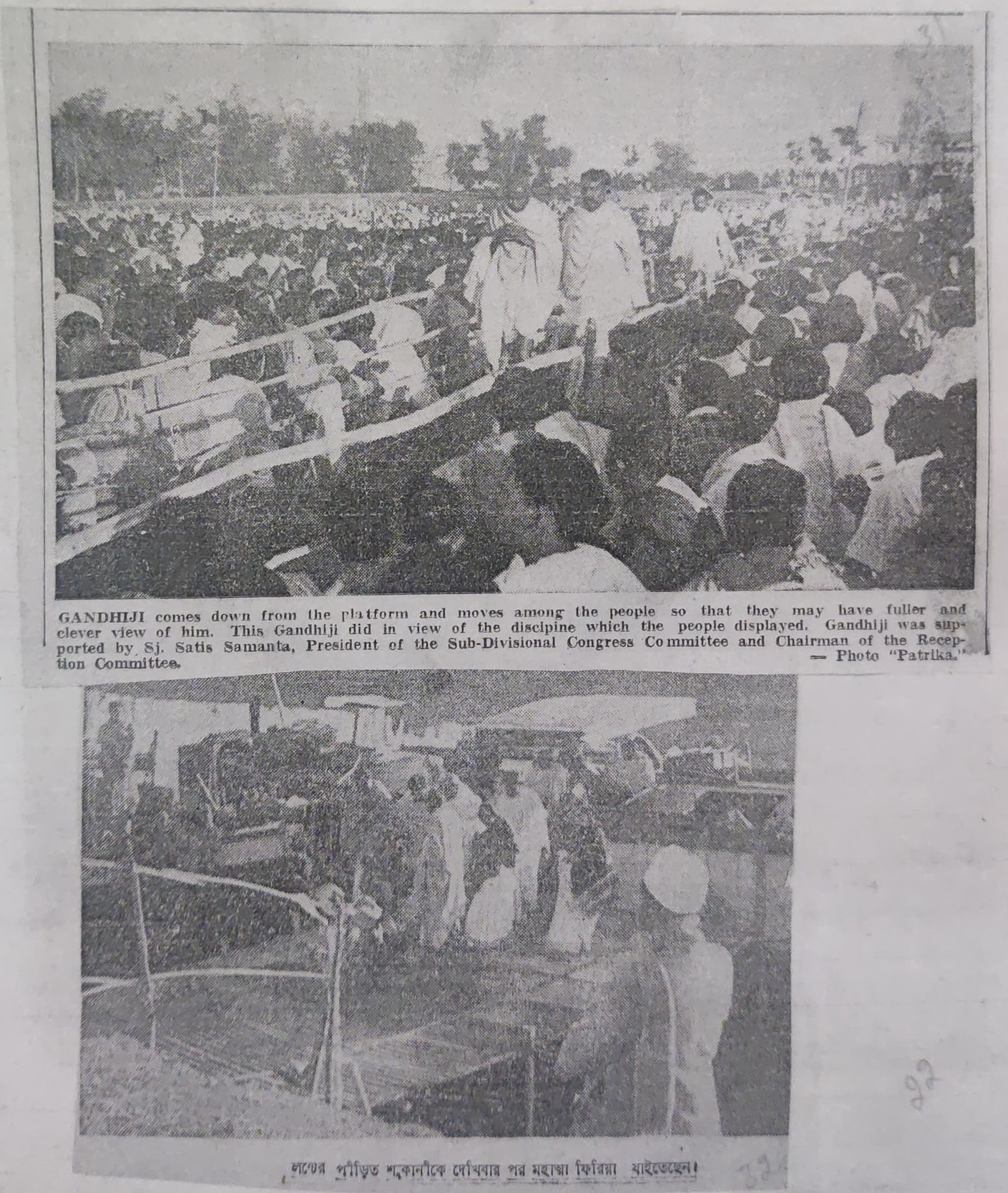

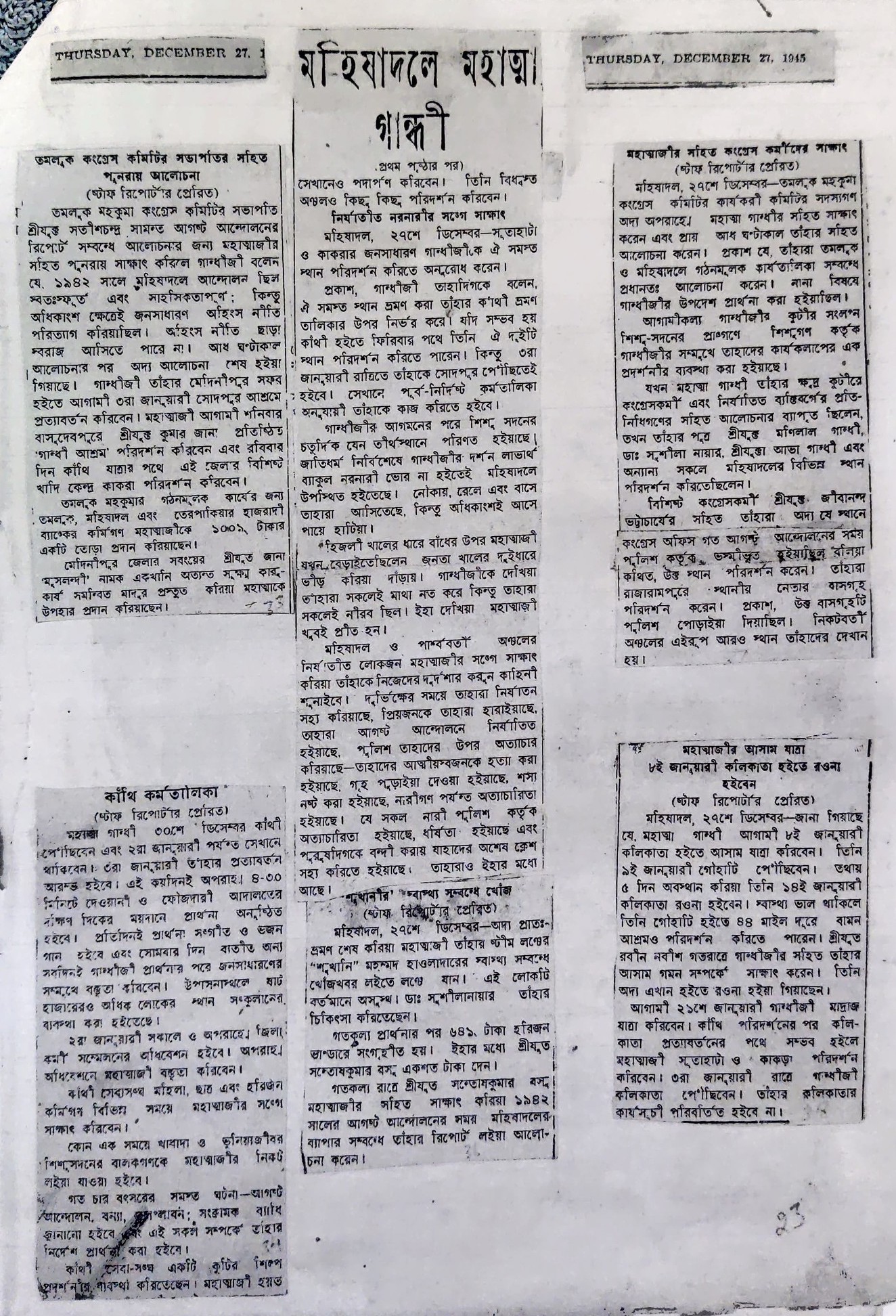

Gandhi in Mahishadal [Thursday, Dec 27, 1945]

Gandhiji met with Tamluk Mahakuma Congress Committee Chairperson, Satis Samanta again, regarding the report concerning the August revolution in Mahisadal. Gandhiji reportedly said that the said revolution was brave and spontaneous, but it shifted from the ethos of non-violence; without non-violence swaraj is impossible to attain. The discussion concluded after an hour of its start. Gandhiji would return to his Sodepore ashram after the completion of his visit to Medinipur, on 3rd January. Gandhiji will visit the ‘Gandhi Ashram’ situated in Basudevpur, established by Kumar Jana. On Sunday, on his way to Kanthi he is scheduled to visit the special khadi unit of the area.

Gandhiji was presented with a bouquet of Rs. 1001, by the Hazradi bank workers of Tamluk, Mahisadal and Terpakia, as a token of appreciation for all the developmental work done by Gandhiji in the Tamluk Mahakuma. Gandhiji was also presented with a ‘Muslandi’, a mat made out of fine and delicate artwork, by Jana.

Image 7

Image 8

Image 9

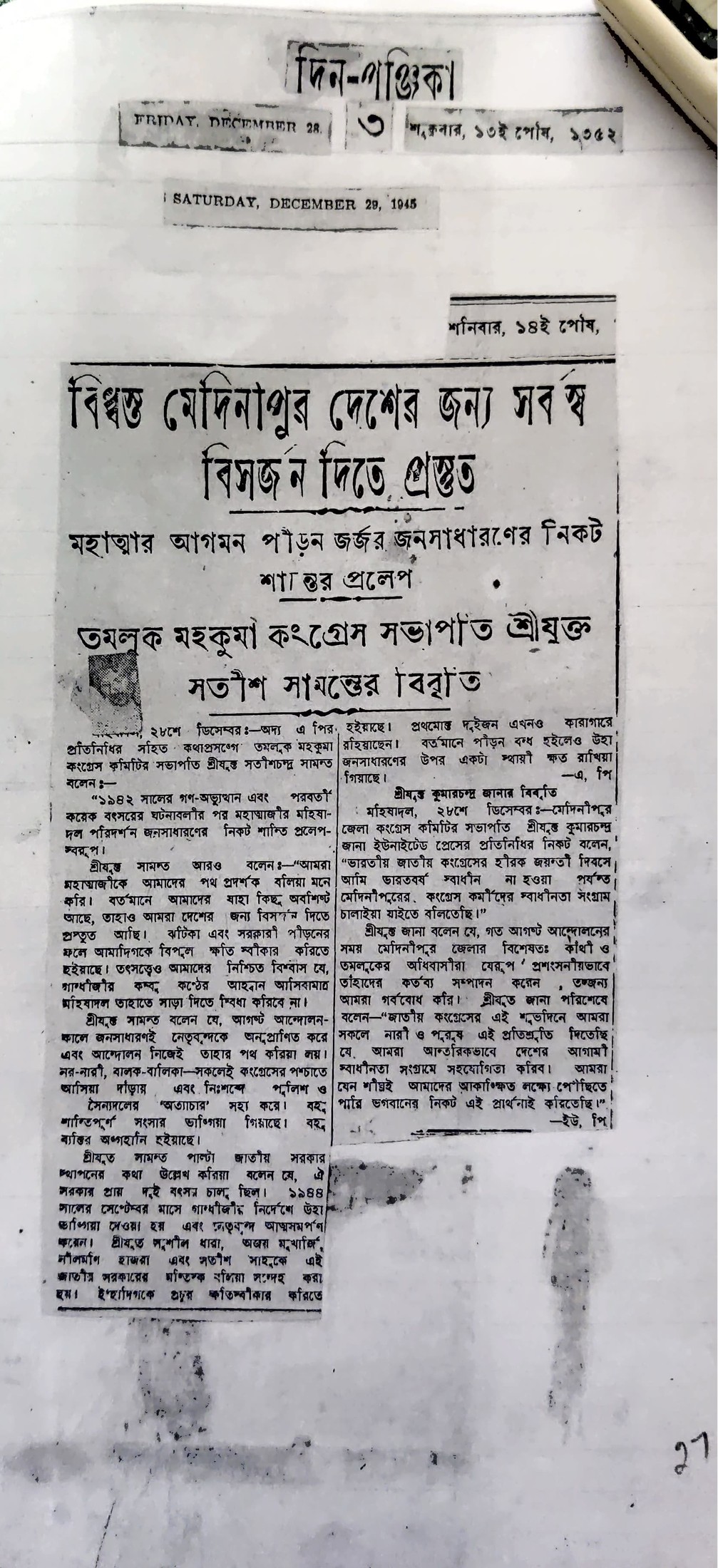

An excerpt from the news column above:

Devastated Medinipur Is Ready to Give It All For The Country

[A statement by Satis Samanta]

Dec 29th, 1945: Satis Samanta says, “We consider Mahatmaji to be our visionary. Whatever we have in us currently (the people of Tamluk), we are ready to risk it all for the betterment of our country. The British government has harassed us inexplicably, but I firmly believe, that with a single indication from Mahatmaji, the people of Mahisadal will come together as a force to reckon with.”

Samanta said that during the August Revolution, the general public inspired the leaders, and carved inroads towards the fruition of the movement. People of all ages have stood firm with the Congress. They have endured harshest blows from the (British) army—many families have been shattered, many lives lost.

About the Tamluk National Government, Mr. Samanta said that the government almost ran for two years. It was discontinued upon Mahatmaji’s advice in 1944. All leaders also surrendered their positions then. Sushil Dhara, Ajay Mukherjee, Nilmoni Hazra and Satish Sahoo were suspected to be masterminds behind the formation of the government. They were charged on many counts. The first two of the aforementioned are still in prison. The wounds have healed but scars remain to haunt the people.

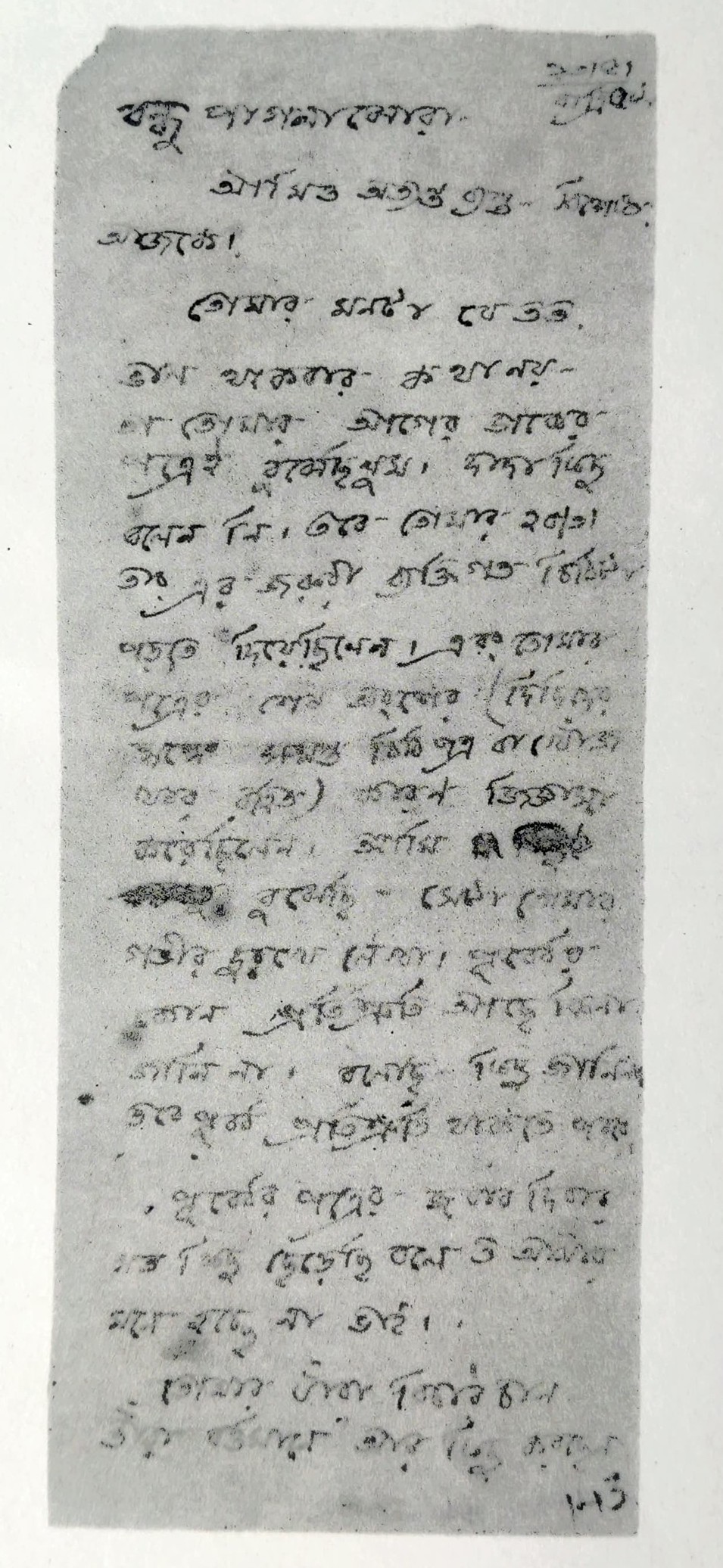

Image 10

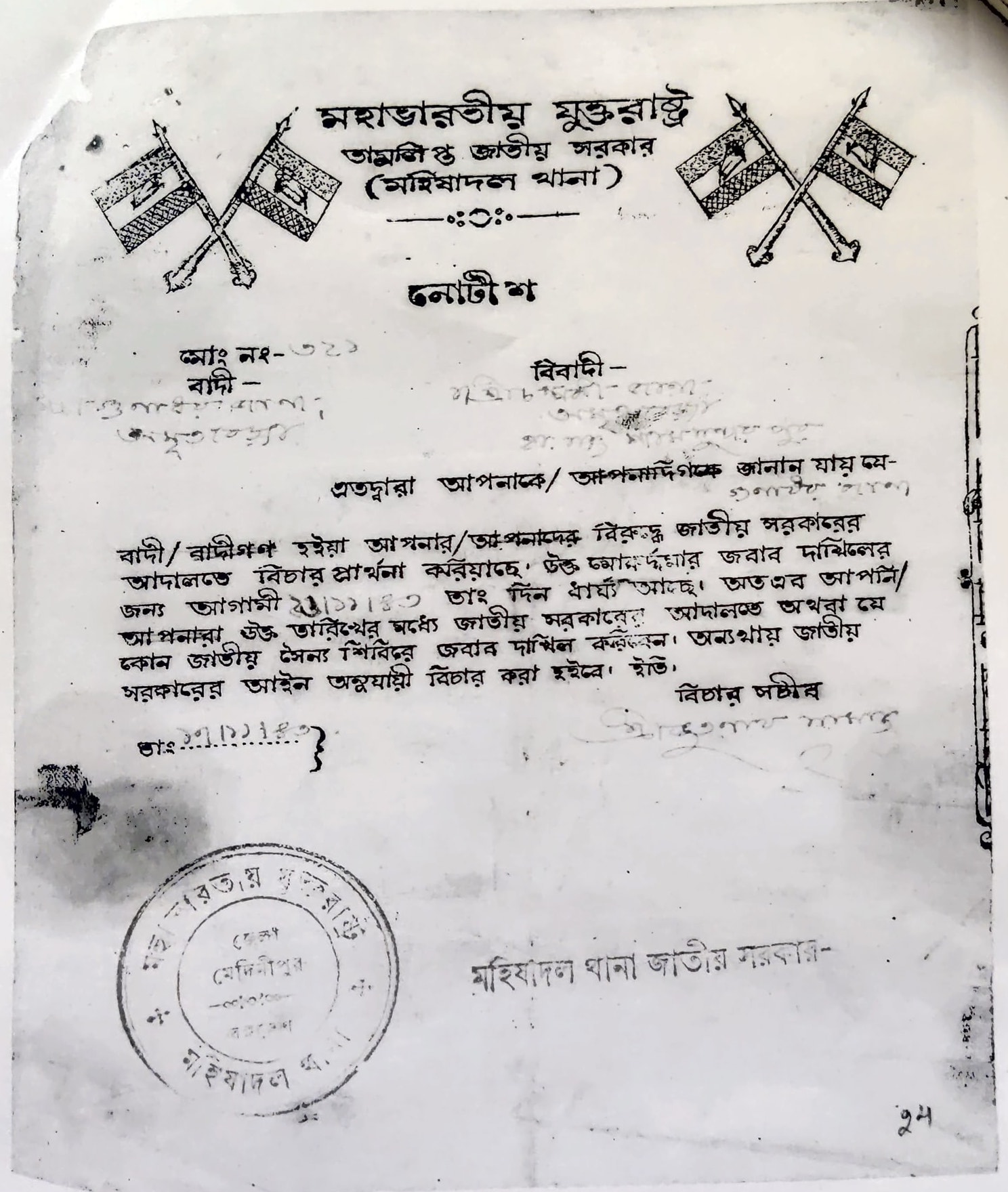

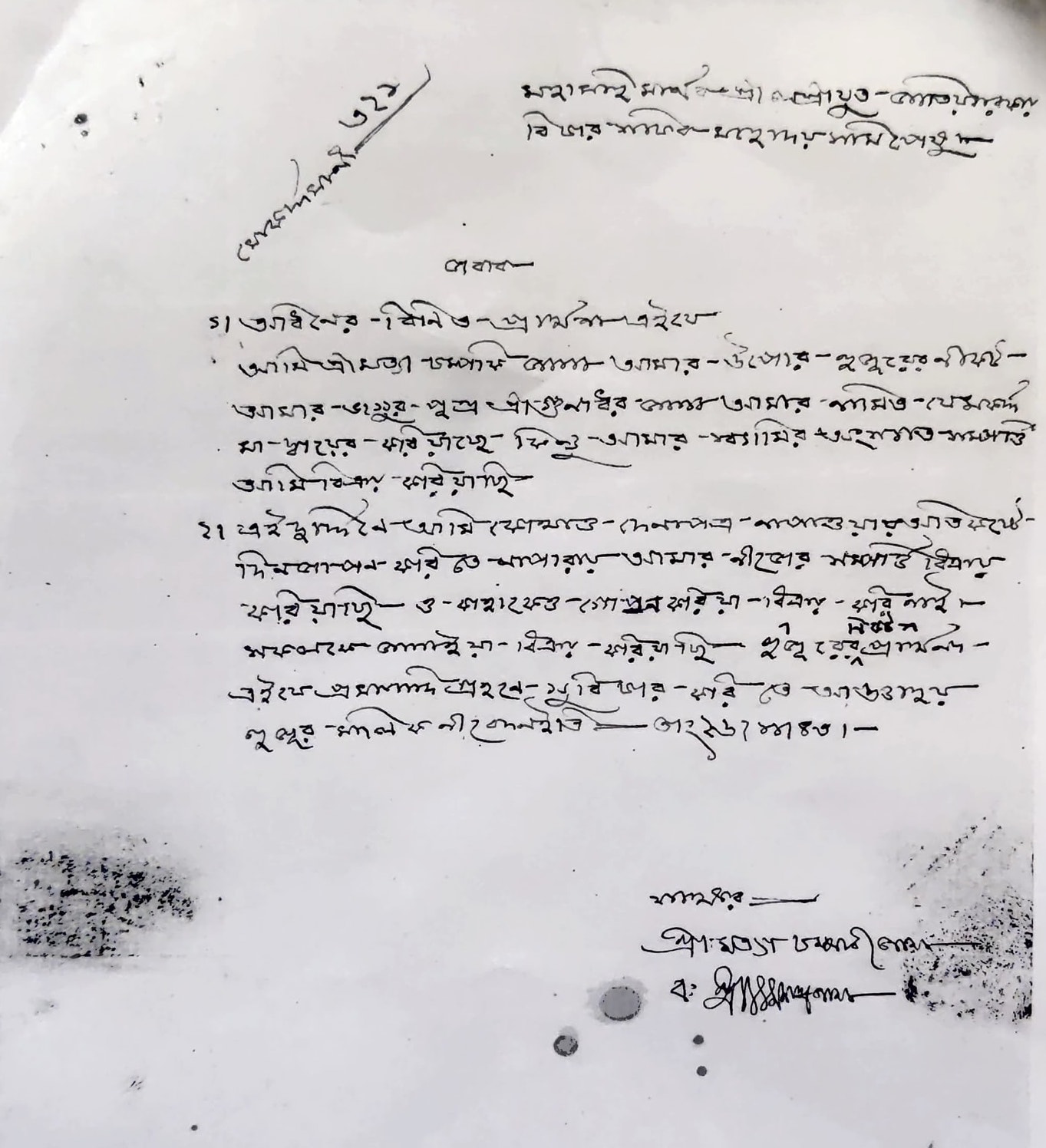

An excerpt from the judicial document above –

The United States of India

Tamralipta National Government

(Mahisadal Thana)

Notice

You are being informed that— (name) plaintiff has complained against you and sought justice at the court of the National Government. (date) is the date for the aforementioned case to be heard. You are hereby ordered to lodge your response at the court of the National Government or at any camp of the National Army. Failing that, action will be taken as per the law of the National Government.

Justice Secretary

Bhootnath Samanta

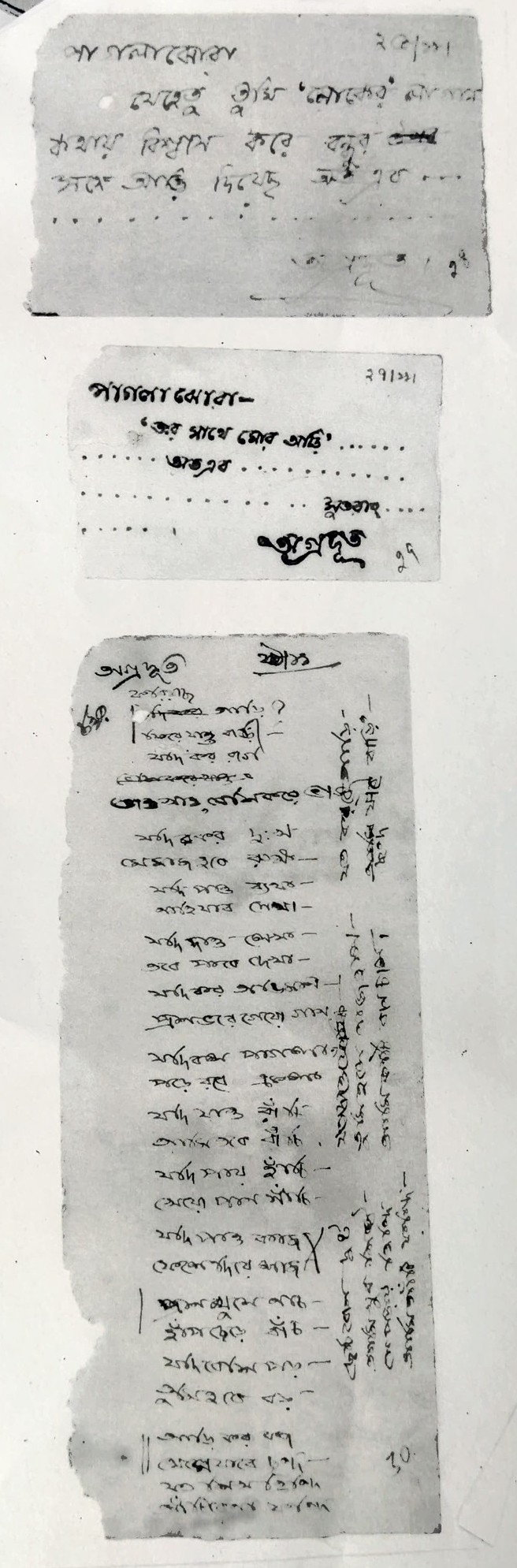

Image 11

Image 12

Image 13

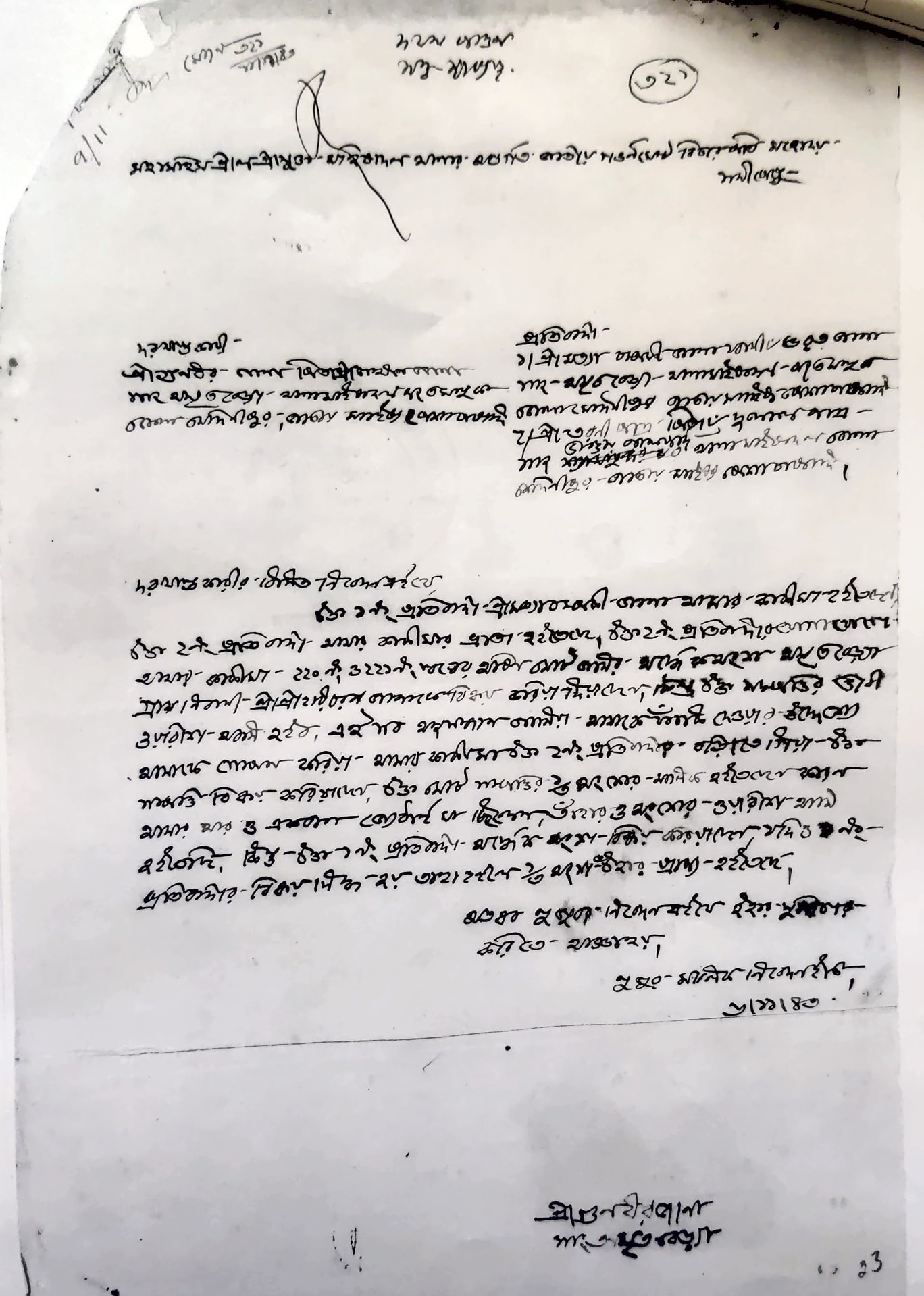

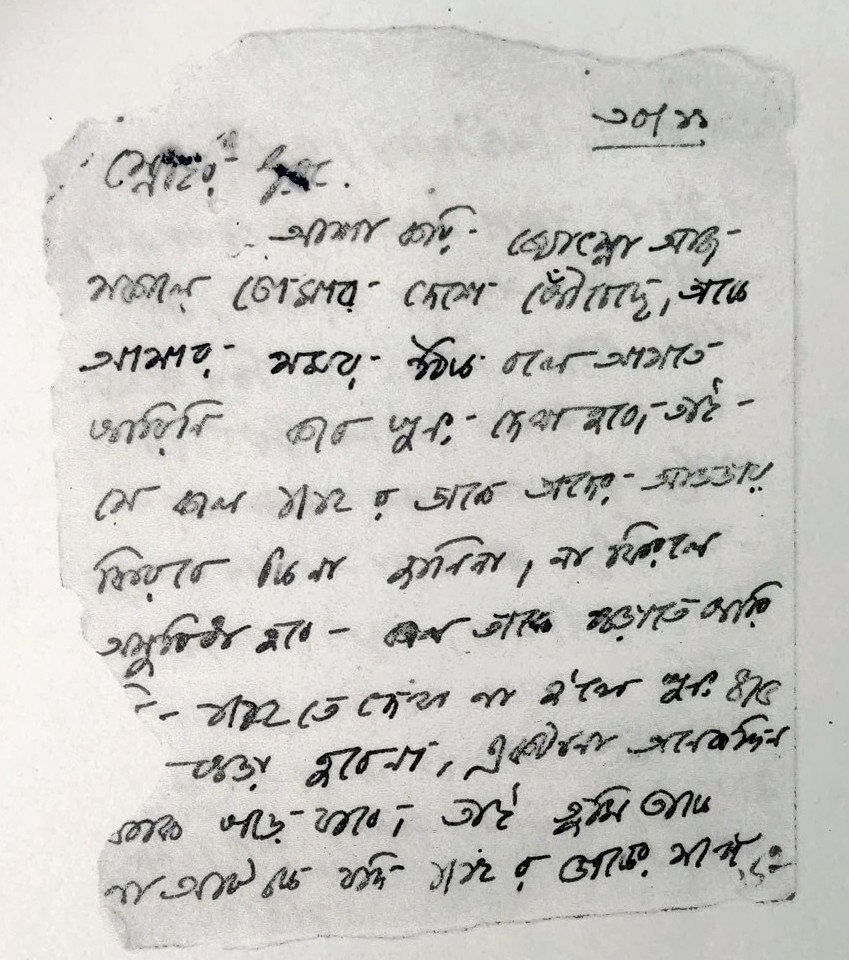

Serial no. 152

Dear G.O.C.,

I hope Jyotsna has reached you safely. I couldn’t tell her when will I be able to see her again. So, I don’t know if she can return by 1st December’s mail. If not, then it will be a problem. I wasn’t able to teach her yesterday—if I don’t meet her on 1st December, then there will again be a gap of 4-5 days. So, please don’t stop her, come with her on 1st December’s mail.

Image 14

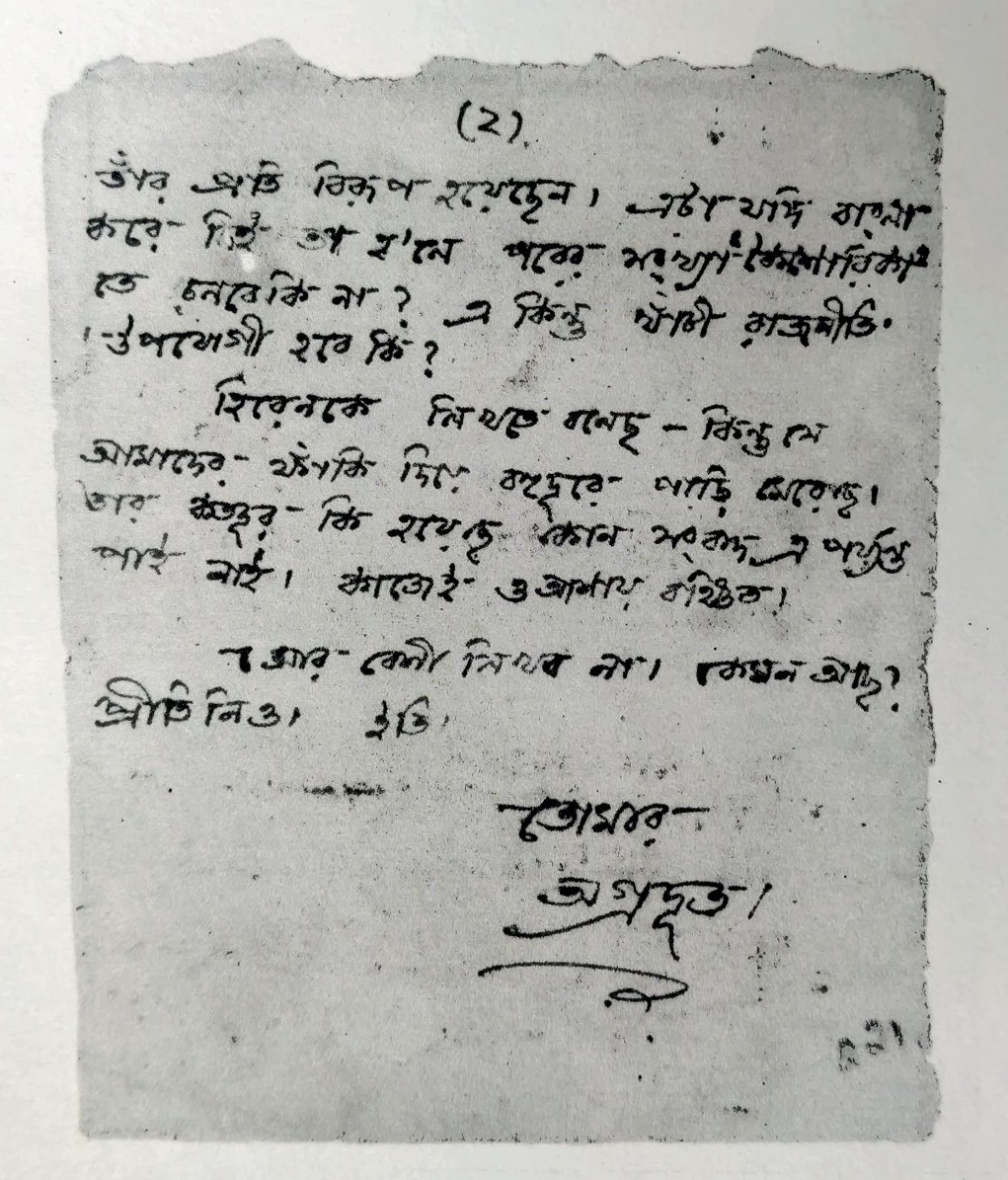

Serial no.- 221

..is offended by him. Can we not translate it in Bengali and publish it in the next issue of ‘Koishorika’? Will it be appropriately political?

You’ve asked me to write to Hiren—but he is beyond our reach now. I have received no news on his whereabouts. Hence, quite naturally, I am very worried.

I will end my letter here. Hope you are fine? Sending you love.

Yours,

Agradoot.

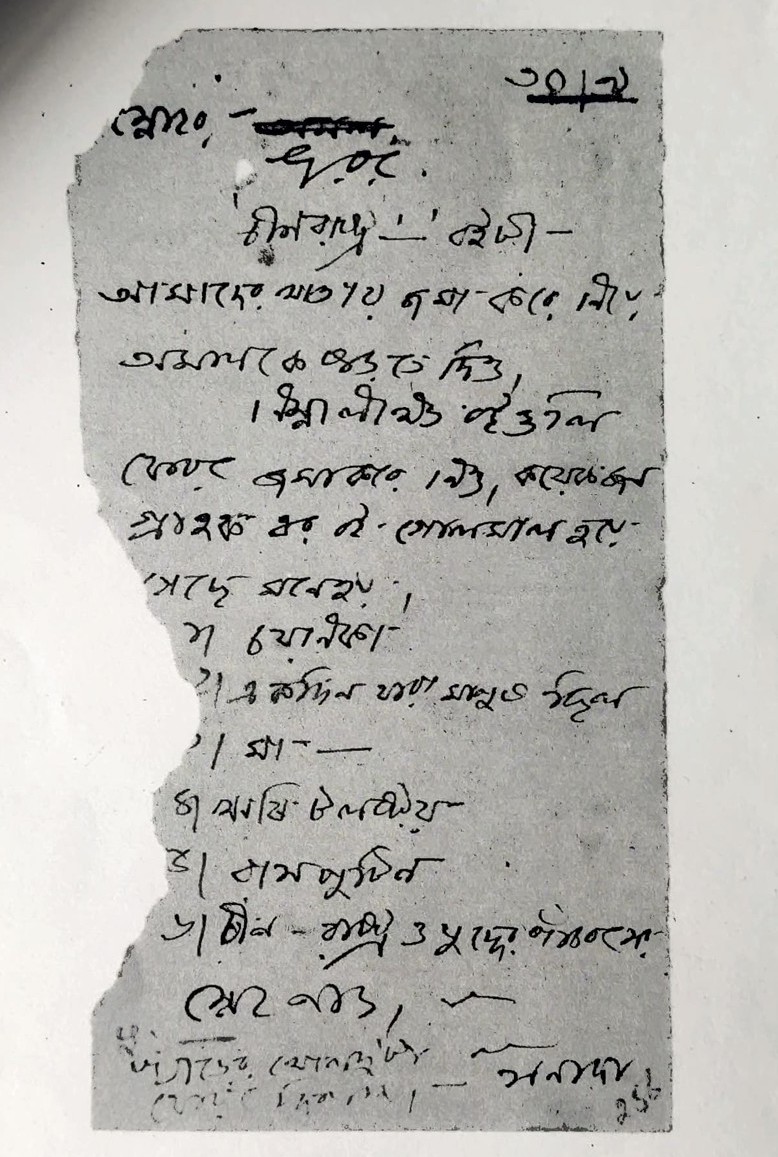

Image 15

Serial no. – 256

Dear G.O.C,

Please get me the book ‘Chin Rashtra’. Make an entry in our copy and lend me to read it. Get the following books returned, there is some confusion with the same.

With love,

Sana Da.

Image 16

Serial no.- 28,29

Paglajhora,

Since you base your opinions on what ‘people’ have to say and have stopped talking to your friend, that’s why………..

–Agradoot

Image 17

Serial no.- 143

My friend Paglajhora,

I am also very busy and exhausted today.

I understand that you do not feel quite well yourself, which I gauged from your previous letter. Dada (elder brother) didn’t say anything. But an important person gave me the letter to read. And I understood from the last part of your letter (any communication with the sisters are reserved), that you have written it with a very heavy heart. I don’t know if there is a prior commitment made—maybe there is. I hope I have not omitted any response to your previous letter.

(The last line is blurry and maybe incomplete)

Aims to make widely available primary sources, work by professional historians and scholars and writers who bring a fresh insight to historical understanding.

| 2500 BC - Present | |

|

2500 BC - Present |

| Tribal History: Looking for the Origins of the Kodavas | |

| 2200 BC to 600 AD | |

|

2200 BC to 600 AD |

| War, Political Violence and Rebellion in Ancient India | |

| 400 BC to 1001 AD | |

|

400 BC to 1001 AD |

| The Dissent of the ‘Nastika’ in Early India | |

| 600CE-1200CE | |

|

600CE-1200CE |

| The Other Side of the Vindhyas: An Alternative History of Power | |

| c. 700 - 1400 AD | |

|

c. 700 - 1400 AD |

| A Historian Recommends: Representing the ‘Other’ in Indian History | |

| c. 800 - 900 CE | |

|

c. 800 - 900 CE |

| ‘Drape me in his scent’: Female Sexuality and Devotion in Andal, the Goddess | |

| 1192 | |

|

1192 |

| Sufi Silsilahs: The Mystic Orders in India | |

| 1200 - 1850 | |

|

1200 - 1850 |

| Temples, deities, and the law. | |

| c. 1500 - 1600 AD | |

|

c. 1500 - 1600 AD |

| A Historian Recommends: Religion in Mughal India | |

| 1200-2020 | |

|

1200-2020 |

| Policing Untouchables and Producing Tamasha in Maharashtra | |

| 1530-1858 | |

|

1530-1858 |

| Rajputs, Mughals and the Handguns of Hindustan | |

| 1575 | |

|

1575 |

| Abdul Qadir Badauni & Abul Fazl: Two Mughal Intellectuals in King Akbar‘s Court | |

| 1579 | |

|

1579 |

| Padshah-i Islam | |

| 1550-1800 | |

|

1550-1800 |

| Who are the Bengal Muslims? : Conversion and Islamisation in Bengal | |

| c. 1600 CE-1900 CE | |

|

c. 1600 CE-1900 CE |

| The Birth of a Community: UP’s Ghazi Miyan and Narratives of ‘Conquest’ | |

| 1553 - 1900 | |

|

1553 - 1900 |

| What Happened to ‘Hindustan’? | |

| 1630-1680 | |

|

1630-1680 |

| Shivaji: Hindutva Icon or Secular Nationalist? | |

| 1630 -1680 | |

|

1630 -1680 |

| Shivaji: His Legacy & His Times | |

| c. 1724 – 1857 A.D. | |

|

c. 1724 – 1857 A.D. |

| Bahu Begum and the Gendered Struggle for Power | |

| 1818 - Present | |

|

1818 - Present |

| The Contesting Memories of Bhima-Koregaon | |

| 1831 | |

|

1831 |

| The Derozians’ India | |

| 1855 | |

|

1855 |

| Ayodhya 1855 | |

| 1856 | |

|

1856 |

| “Worshipping the dead is not an auspicious thing” — Ghalib | |

| 1857 | |

|

1857 |

| A Subaltern speaks: Dalit women’s counter-history of 1857 | |

| 1858 - 1976 | |

|

1858 - 1976 |

| Lifestyle as Resistance: The Curious Case of the Courtesans of Lucknow | |

| 1883 - 1894 | |

|

1883 - 1894 |

| The Sea Voyage Question: A Nineteenth century Debate | |

| 1887 | |

|

1887 |

| The Great Debaters: Tilak Vs. Agarkar | |

| 1893-1946 | |

|

1893-1946 |

| A Historian Recommends: Gandhi Vs. Caste | |

| 1897 | |

|

1897 |

| Queen Empress vs. Bal Gangadhar Tilak: An Autopsy | |

| 1913 - 1916 Modern Review | |

|

1913 - 1916 |

| A Young Ambedkar in New York | |

| 1916 | |

|

1916 |

| A Rare Account of World War I by an Indian Soldier | |

| 1917 | |

|

1917 |

| On Nationalism, by Tagore | |

| 1918 - 1919 | |

|

1918 - 1919 |

| What Happened to the Virus That Caused the World’s Deadliest Pandemic? | |

| 1920 - 1947 | |

|

1920 - 1947 |

| How One Should Celebrate Diwali, According to Gandhi | |

| 1921 | |

|

1921 |

| Great Debates: Tagore Vs. Gandhi (1921) | |

| 1921 - 2015 | |

|

1921 - 2015 |

| A History of Caste Politics and Elections in Bihar | |

| 1915-1921 | |

|

1915-1921 |

| The Satirical Genius of Gaganendranath Tagore | |

| 1924-1937 | |

|

1924-1937 |

| What were Gandhi’s Views on Religious Conversion? | |

| 1900-1950 | |

|

1900-1950 |

| Gazing at the Woman’s Body: Historicising Lust and Lechery in a Patriarchal Society | |

| 1925, 1926 | |

|

1925, 1926 |

| Great Debates: Tagore vs Gandhi (1925-1926) | |

| 1928 | |

|

1928 |

| Bhagat Singh’s dilemma: Nehru or Bose? | |

| 1930 Modern Review | |

|

1930 |

| The Modern Review Special: On the Nature of Reality | |

| 1932 | |

|

1932 |

| Caste, Gandhi and the Man Beside Gandhi | |

| 1933 - 1991 | |

|

1933 - 1991 |

| Raghubir Sinh: The Prince Who Would Be Historian | |

| 1935 | |

|

1935 |

| A Historian Recommends: SA Khan’s Timeless Presidential Address | |

| 1865-1928 | |

|

1865-1928 |

| Understanding Lajpat Rai’s Hindu Politics and Secularism | |

| 1935 Modern Review | |

|

1935 |

| The Modern Review Special: The Mind of a Judge | |

| 1936 Modern Review | |

|

1936 |

| The Modern Review Special: When Netaji Subhas Bose Was Wrongfully Detained for ‘Terrorism’ | |

| 1936 | |

|

1936 |

| Annihilation of Caste: Part 1 | |

| 1936 Modern Review | |

|

1936 |

| The Modern Review Special: An Indian MP in the British Parliament | |

| 1936 | |

|

1936 |

| Annihilation of Caste: Part 2 | |

| 1936 | |

|

1936 |

| A Reflection of His Age: Munshi Premchand on the True Purpose of Literature | |

| 1936 Modern Review | |

|

1936 |

| The Modern Review Special: The Defeat of a Dalit Candidate in a 1936 Municipal Election | |

| 1937 Modern Review | |

|

1937 |

| The Modern Review Special: Rashtrapati | |

| 1938 | |

|

1938 |

| Great Debates: Nehru Vs. Jinnah (1938) | |

| 1942 Modern Review | |

|

1942 |

| IHC Uncovers: A Parallel Government In British India (Part 1) | |

| 1942-1945 | |

|

1942-1945 |

| IHC Uncovers: A Parallel Government in British India (Part 2) | |

| 1946 | |

|

1946 |

| Our Last War of Independence: The Royal Indian Navy Mutiny of 1946 | |

| 1946 | |

|

1946 |

| An Artist’s Account of the Tebhaga Movement in Pictures And Prose | |

| 1946 – 1947 | |

|

1946 – 1947 |

| “The Most Democratic People on Earth” : An Adivasi Voice in the Constituent Assembly | |

| 1946-1947 | |

|

1946-1947 |

| VP Menon and the Birth of Independent India | |

| 1916 - 1947 | |

|

1916 - 1947 |

| 8 @ 75: 8 Speeches Independent Indians Must Read | |

| 1947-1951 | |

|

1947-1951 |

| Ambedkar Cartoons: The Joke’s On Us | |

| 1948 | |

|

1948 |

| “My Father, Do Not Rest” | |

| 1940-1960 | |

|

1940-1960 |

| Integration Myth: A Silenced History of Hyderabad | |

| 1948 | |

|

1948 |

| The Assassination of a Mahatma, the Princely States and the ‘Hindu’ Nation | |

| 1949 | |

|

1949 |

| Ambedkar warns against India becoming a ‘Democracy in Form, Dictatorship in Fact’ | |

| 1950 | |

|

1950 |

| Illustrations from the constitution | |

| 1951 | |

|

1951 |

| How the First Amendment to the Indian Constitution Circumscribed Our Freedoms & How it was Passed | |

| 1967 | |

|

1967 |

| Once Upon A Time In Naxalbari | |

| 1970 | |

|

1970 |

| R.C. Majumdar on Shortcomings in Indian Historiography | |

| 1973 - 1993 | |

|

1973 - 1993 |

| Balasaheb Deoras: Kingmaker of the Sangh | |

| 1975 | |

|

1975 |

| The Emergency Package: Shadow Power | |

| 1975 | |

|

1975 |

| The Emergency Package: The Prehistory of Turkman Gate – Population Control | |

| 1977 – 2011 | |

|

1977 – 2011 |

| Power is an Unforgiving Mistress: Lessons from the Decline of the Left in Bengal | |

| 1984 | |

|

1984 |

| Mrs Gandhi’s Final Folly: Operation Blue Star | |

| 1916-2004 | |

|

1916-2004 |

| Amjad Ali Khan on M.S. Subbulakshmi: “A Glorious Chapter for Indian Classical Music” | |

| 2008 | |

|

2008 |

| Whose History Textbook Is It Anyway? | |

| 2006 - 2009 | |

|

2006 - 2009 |

| Singur-Nandigram-Lalgarh: Movements that Remade Mamata Banerjee | |

| 2020 | |

|

2020 |

| The Indo-China Conflict: 10 Books We Need To Read | |

| 2021 | |

|

2021 |

| Singing/Writing Liberation: Dalit Women’s Narratives | |

Leave a Reply