“They would say ‘means are after all means’. I would say means are after all everything… There is no wall of separation between means and end.”

—Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi

Let us begin with the introduction of Tripurdaman Singh’s book Sixteen Stormy Days: The Story of the First Amendment to the Constitution of India, which takes us back to 1951, when India had a provisional parliament elected on a limited franchise. (Members of the former constituent assembly were members of this provisional parliament. The franchise was ‘limited’ because they had been elected indirectly by members of the provincial assemblies. Also, the provisional parliament consisted of one house instead of two. This state of affairs carried on till 1952, when the country’s first general elections were concluded and a parliament was elected directly by the people of India.)

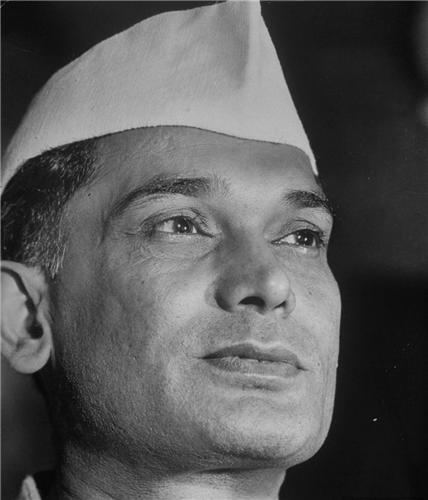

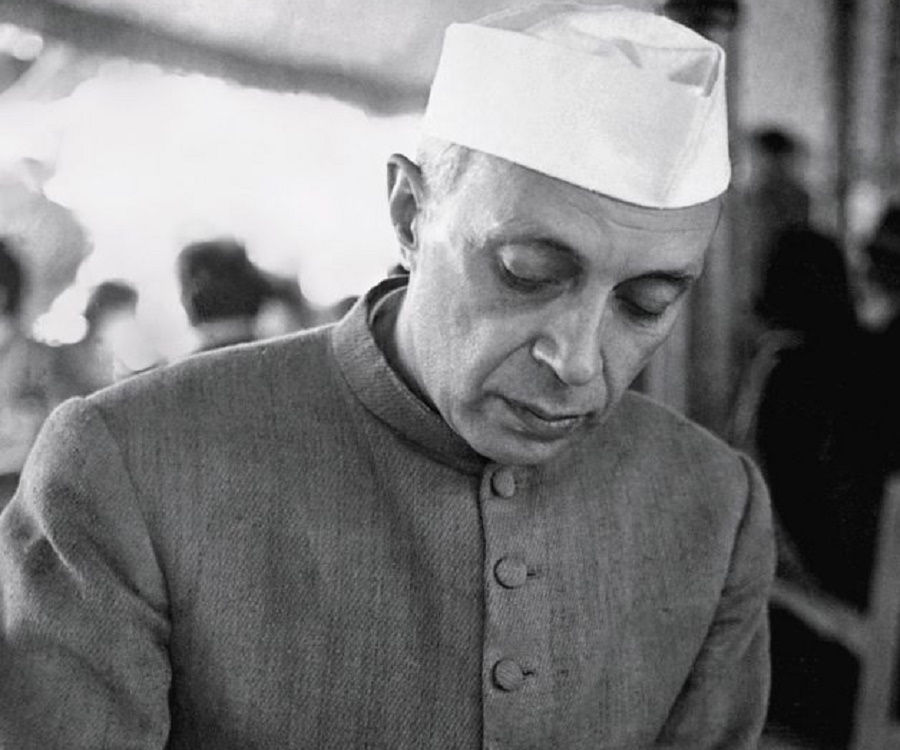

Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru declared that while fundamental rights, individual liberty and freedom were ideas that had dominated the nineteenth century, they were now overtaken by the bigger and better ideas of the twentieth: dynamic social reform and social engineering, enshrined in the Directive Principles of State Policy as well as the programmes of the Congress party (Jawaharlal Nehru, 16 May 1951, Parliamentary Debates, Part II, Vol. XII, p. 8822).

But for ideas like “Land reform, zamindari abolition, nationalization of industry, reservations for ‘backward classes’ in employment and education” to see the light of day, many a hurdle remained to be crossed. Add to this the fact that a “pliant press”, as Nehru had probably hoped for, was not forthcoming and nothing could be done about this. “Armed with Part III of the new constitution—guaranteeing the fundamental rights of citizens—zamindars, businessmen, editors and concerned individuals had repeatedly taken the Central and state governments to court over their attempts to curtail civil liberties, regulate the press, limit upper-caste students in universities and acquire zamindari property,” writes Singh. “Over the fourteen months the constitution had been in force, the courts had come down heavily on the side of the citizens and struck mighty blows against the government.”

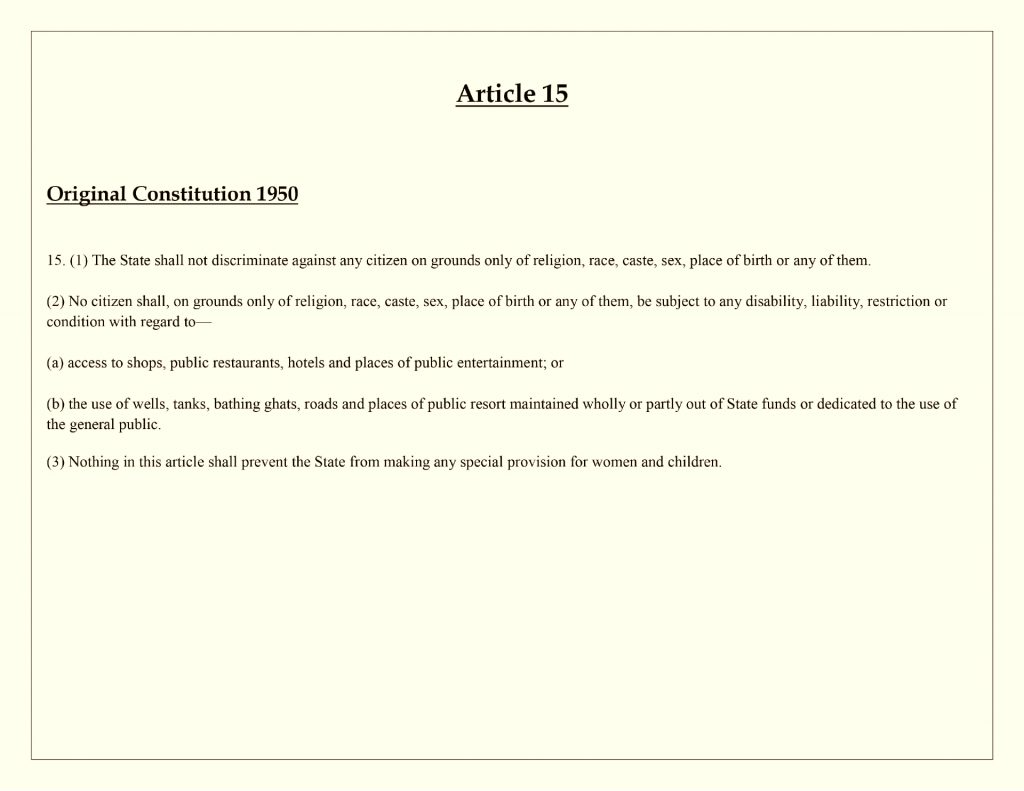

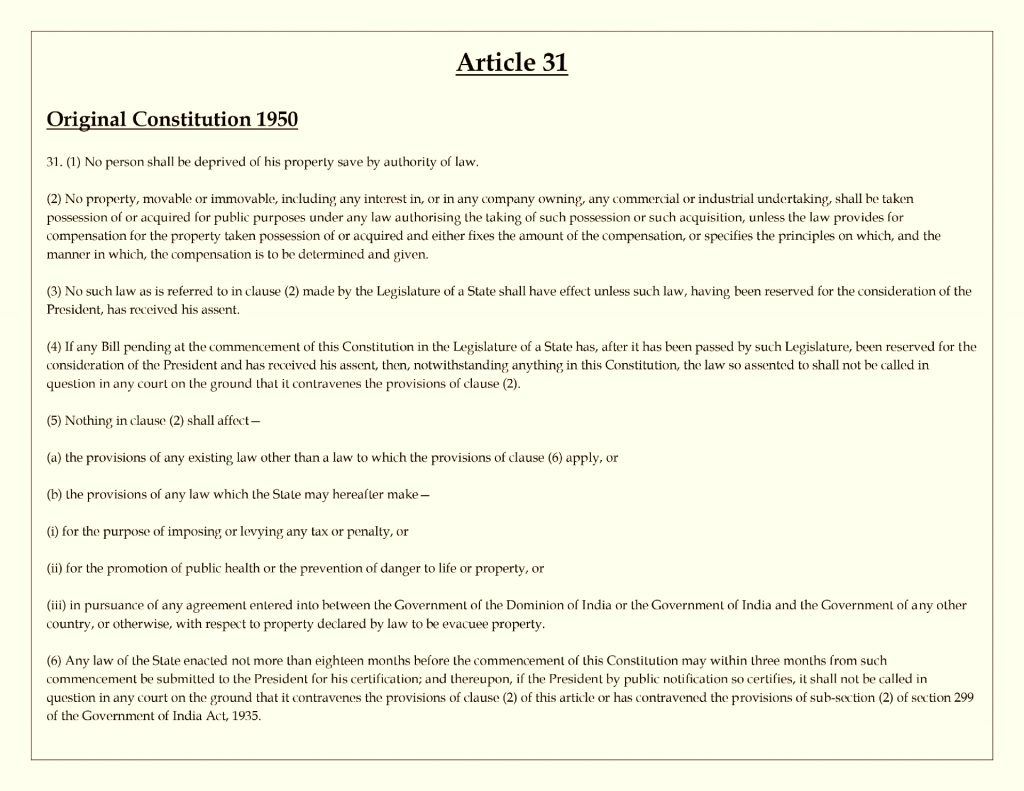

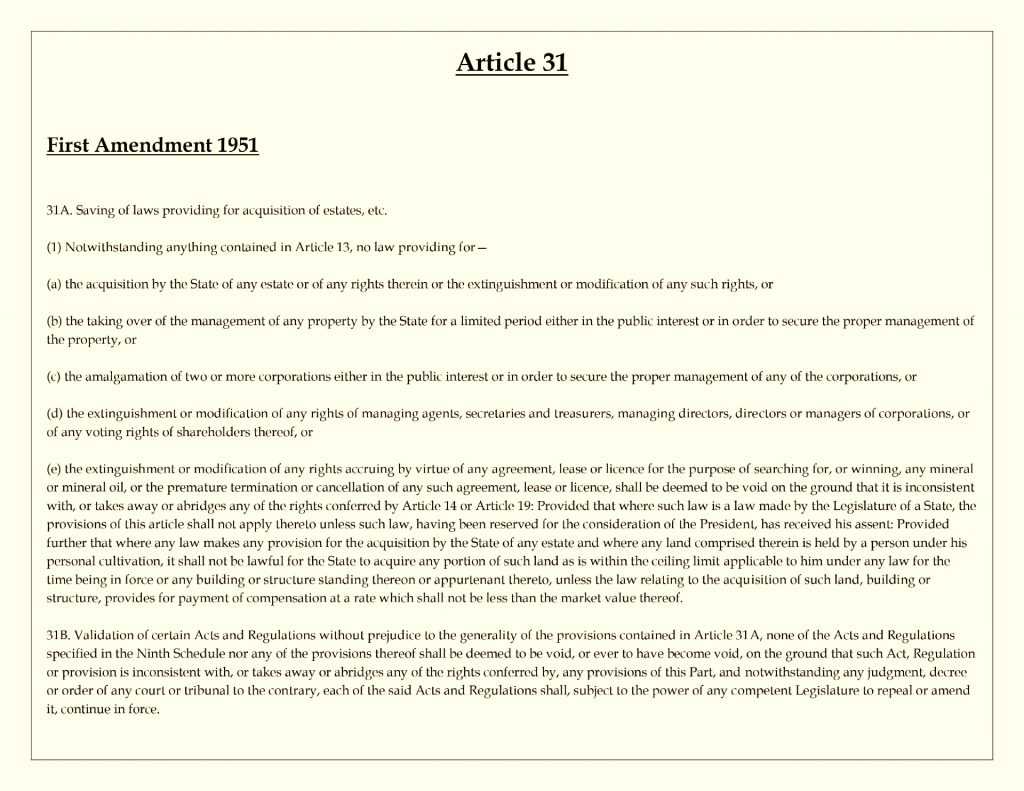

To cite a few examples, the government’s attempt to censor The Organiser (an RSS newspaper) and Cross Roads (a left-leaning weekly) had been countermanded. Laws used to censor and punish the press had been declared void by the Supreme Court because of the violation of the freedom of speech. The Allahabad High Court had passed injunctions restraining the government from implementing the newly passed Zamindari Abolition Act. The Patna High Court had declared the State Management of Estates and Tenures Act to be ultra vires of the constitution for violating Articles 14 (the right to equality) and 31 (the right to property). The Central Provinces and Berar Regulation of Manufacture of Bidis Act, which controlled and regulated bidi production, was held void by the Supreme Court because it violated the right to carry on any trade or profession. The Madras High Court struck down the ‘Communal Government Order’ granting caste-based reservations in educational institutions for contravening Article 15(1) preventing discrimination on caste, communal, racial and linguistic grounds. The Supreme Court upheld this decision and also struck down communal reservations in government jobs.

And yet, even as “the Congress programme to remake India” encountered such “formidable roadblocks”—“fundamental rights guaranteed by the Constitution, tenacious citizens, a belligerent press and a resolute judiciary determined to vigorously uphold fundamental freedoms”—the country’s first general elections were looming close (eventually held at the end of 1951, and carrying on into 1952).

A major problem for the Congress, as Nehru stated in a note to the Home Ministry (25 July, 1950, Selected Works of Jawaharlal Nehru, edited by Sarvepalli Gopal, Vol. 14/2, p. 223) was explaining the situation to the people. “Having raised their expectations and asked them to believe in the promises of Congress leaders, how were they to now go back to them and explain legal and constitutional niceties?” Singh writes. “Who was going to tell the people that the word of the government and the prime minister was not the law, that there was now a greater power, the Constitution of India? And what might happen if they did?”

Nehru wrote to his chief ministers: “It is impossible to hang up urgent social changes because the Constitution comes in the way… We shall have to find a remedy, even though this might involve a change in the Constitution.”

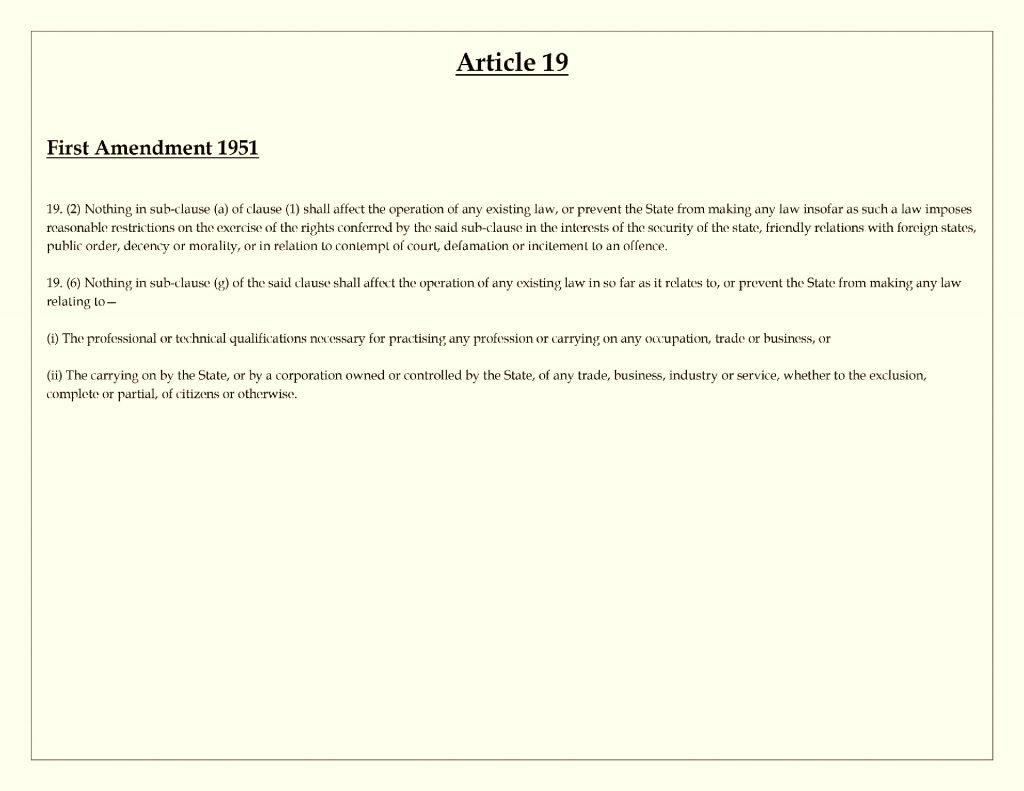

And so, eventually, the prime minister introduced the Constitution (First Amendment) Bill in Parliament on 12 May, 1951. Singh sums up the bill in a nutshell. If passed, it would:

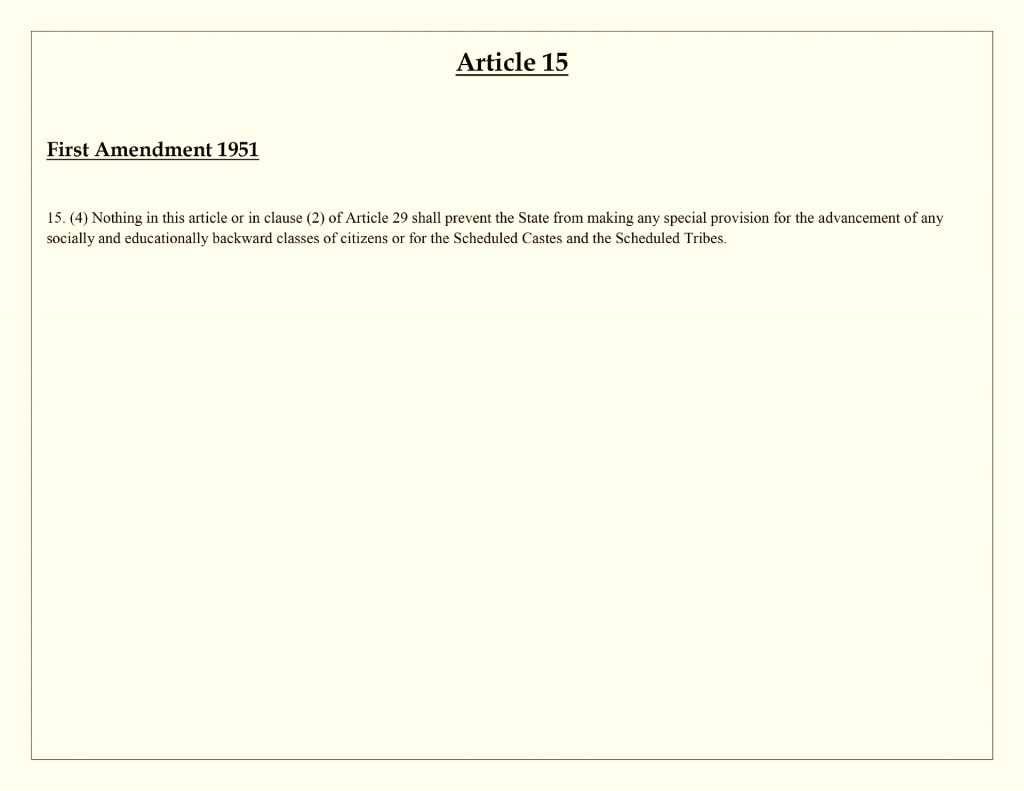

– “introduce new grounds on which freedom of speech could be curbed— public order, the interests of the security of the state” (originally the grounds “had been limited to libel, slander and defamation, contempt of court and anything that undermined the security of the state or tended to overthrow it.”);

– it would “enable caste-based reservations by restricting the right to freedom against discrimination from applying to government provisions for the advancement of backward classes”;

– it would “circumscribe the right to property and validate zamindari abolition by adding two new articles empowering the state to acquire estates without paying equitable compensation and ensuring that any law providing for such acquisition could not be deemed void even if it abridged this right”;

– and, finally, it would “introduce a special schedule where laws could be placed to make them immune to judicial challenge even if they violated fundamental rights”.

Singh also outlines how the vision of a constitution of India that defended the “personal liberties of individual Indians” had been a crucial demand of the nationalist struggle for independence: “From the time the demand was first articulated in 1895 through the Constitution of India Bill (popularly called the Swaraj Bill and rumoured to have been authored by Bal Gangadhar Tilak), through the Commonwealth of India Bill in 1925, the Motilal Nehru Report in 1928 and the Purna Swaraj resolution of 1930, the journey had been long and arduous.” Further, he elaborates on how, when the new Constituent Assembly first convened at 11 am on 9 December 1946, “no one had been in doubt as to the momentous nature of the task at hand”. Dr. Bhim Rao Ambedkar described individual rights and their safeguards as the “very soul of the Constitution and the very heart of it”. “Indeed if I may say so,” he had asserted in the Constituent Assembly. “If things were to go wrong under the new Constitution, the reason will not be that we had a bad Constitution. What we will have to say is that man was vile.”

And yet, the Constitution (First Amendment) Bill was passed, and the changes ran so deep that the consequent constitution was called “the second constitution” or “the Nehruvian constitution” by legal historians like Prof. Upendra Baxi.

Singh’s book is the story of how the Constitution went from “being a charter for freedom for India’s people and the fulfilment of their dreams in 1950 to an impediment in the way of the will of the same by 1951”. The chapter we have chosen to carry here below, on Republic Day, called ‘The Battle Rages’, is the story of how things played out, in the provisional parliament and outside it, in the final days of the old constitution. The chapter begins with the Speaker G.V. Mavalankar, like the President Rajendra Prasad, expressing his objections over the Constitution (First Amendment) Bill to Prime Minister Nehru and ends with the bill being passed. It’s gripping account of events gives the reader a sense of being in the middle of history as it is being made (or unmade, as the case may be) as well as the occasional vantage point from which to analyse this history.

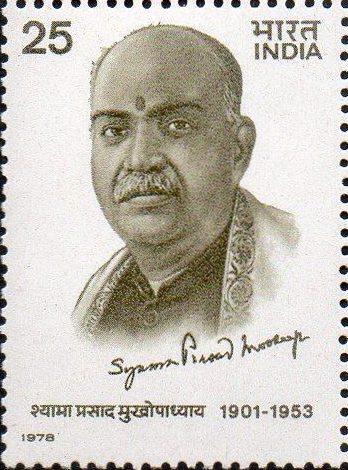

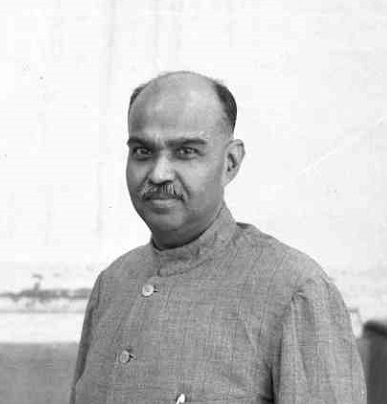

The chapter, like the book, also questions “easy dichotomies that have traditionally been drawn… between liberal and authoritarian visions of India” which are “more than blurred when taken up for closer examination”. Singh, calling the battle over the first amendment “the first battle of Indian liberalism” writes about the “unlikeliest of characters” making up the list of the first defenders of our individual rights and freedoms: “Hindu nationalists like S.P. Mookerjee and M.R. Jayakar, Gandhian stalwarts like Acharya Kripalani, committed socialists like Shibban Lal Saksena and Jayaprakash Narayan, conscientious Congress rebels like H.V. Kamath, Syamnandan Sahay and K.K. Bhattacharya, jurists like Pran Nath Mehta and M.C. Chagla, press associations, editors, lawyers and businessmen; men whose ideological and editorial successors today might scarcely believe (but would do well to remember) that their predecessors held the views they did.” And on the other side, pushing for this amendment, we have champions of freedom like Prime Minister Nehru and Law Minister Ambedkar who were holding strong on the magnificence of the Constitution and sanctity of fundamental rights less than a year or two before the amendment was presented in parliament. “It (the book) is the story of how the Government of India discovered that mouthing platitudes to civil liberties was one thing, and upholding them as principles quite another. It is the story of how the primacy of a government’s social agenda over the Constitution and individual freedom was affirmed.”

So let us come back to where we began – the question of ends and means – and examine quickly the legacy of the first amendment and its passing and where it has left us today:

– The moral precedent set by the passing of such an amendment by a provisional parliament, elected on a limited franchise, even as the country’s first general elections are just around the corner, is unconscionable to say the least.

Further, there was the question of there being only one house in this parliament. President Prasad had written to Alladi Krishnaswamy Aiyar before giving his assent to the Bill. Singh writes:

“The problem as he saw it was twofold. First, the provisional parliament only had one House whereas Article 368, which gave Parliament the power to amend the Constitution, required a two-thirds majority in both Houses. Was a single chamber provisional parliament then competent to amend the Constitution?

“Second, the government had got around this difficulty by adapting Article 368 to temporarily refer to Parliament rather than two separate Houses by using the Constitution (Removal of Difficulties) Order No. 2—issued by the president on 26 January 1950 (under powers granted to him by Article 392) to make minor adaptations to the Constitution in order to remove any procedural difficulties that arose before a full Parliament was elected. Could this adaptation itself be ultra vires since, under the guise of removing difficulties, it effectively (albeit temporarily) amended Article 368 without adhering to the amending procedure as the article itself required?”

Aiyar’s reply is not on record. Historian Granville Austin notes that, “Earlier, when Prasad had addressed him with such concerns, Aiyar had told him he must give his assent.” Prasad assented to the bill on 18 June, 1951.

– This chapter shows how the Speaker Mavalankar, the opposition leader Mookerjee and the All India Newspaper Editors Conference (AINEC) pushed emphatically for the solicitation of a “wide range of public opinion” before such a drastic move. The passing of such a major amendment without the inviting of this “wide range of public opinion” set a dangerous precedent that has been followed, in varying degrees, by many Indian governments since, including the current one.

– The creation of a (Ninth) schedule where laws could be placed to make them immune to judicial review, was problematic in two respects: it took away the teeth of the judiciary, blatantly infringing upon the principles of ‘separation of powers’ and ‘checks and balances’ and, as members of parliament have been shown to point out in this chapter: “The experience gained under the Constitution was insufficient to justify an amendment, they did not have the texts of the laws to be validated [laws that would be placed in the Ninth Schedule].”

– The worst and most direct legacy of the first amendment is the chilling impact it has had, and continues to have, on free speech in India. Singh writes: “Activists, human rights figures, intellectuals, writers, historians, politicians, journalists and even comedians have often faced the brunt of a repressive state and onerous laws, for which the enabling constitutional infrastructure was built by this amendment in 1951.” Let us take the example of Section 124A of the Indian Penal Code, which deals with sedition. “Not even its most prominent critics ever note that the founding fathers of the Constitution of India did not intend for it to remain on the statute books. It had found no constitutional support in the original Constitution,” writes Singh. “It was revalidated in 1951, despite intense opposition, by the introduction of new grounds under which free speech could be curtailed— ‘the interests of the security of the state’ rather than undermining the security of the state or overthrowing it. Far from being a simple remnant of colonialism, sedition is the outcome of the first amendment of the Constitution.”

Readers would do well to view the argument against the first amendment – as laid out in this chapter and this book – through an intrinsic lens, instead of an ideological one. It speaks not to the question of what you think of the social agenda of the government of the time (eg. the abolition of the zamindari, land reform, nationalization, reservations for social and educationally Vs. economic backward classes) but to the question of whether you believe that due process and free speech should be the irrevocable cornerstones of a democracy.

For, if you don’t, and believe instead in a revolution that can build a new order on a foundation that excludes these cornerstones, do keep in mind that any order built without these two cornerstones – due process and free speech – can just as soon crumble or be reversed.

The reversal might well employ similar authoritarian weapons, premeditated around a disregard for due process and free speech.

“India has often been said to be flirting with authoritarianism,” Singh writes at the conclusion of his book. “Yet, this was not always so. There was once a time, before authoritarianism became enshrined in its Constitution, when India also flirted with liberalism. At that moment, Mookerjee had warned Nehru to stick with the original Constitution, that he was creating legal tools that would one day be wielded by his opponents, that his rule or that of his ideological co-travellers would not be eternal. It is a warning that every government and every citizen would do well to remember.”

On the evening of 15 May 1951, the evening before fireworks began in Parliament, Speaker G.V. Mavalankar wrote to Prime Minister Nehru to express his objections to the proposed amendments. Echoing the critics outside the Congress, Mavalankar thought the amendment ill-timed and unnecessary in the present circumstances. Like the president, he didn’t believe there was any pressing need to curb free speech, and even if there was, the amendment must not be pushed through without soliciting a wide range of public opinion. He also found the changes to Article 31 a grave infringement which would effectively deprive the individual of all fundamental rights in relation to property, on which, he argued, most peaceful progress and social reorganization depended.

‘We have felt the urgency of having some such amendment because the situation in the zamindari areas is becoming increasingly difficult,’ replied Nehru. ‘We are on the eve of what might be called a revolutionary situation . . . It is in our opinion, very important that rapid effect should be given to the Zamindari Abolition Acts.’ ‘Any attempt to postpone this measure rather indefinitely may well lead to very serious consequences,’ he admitted to the Speaker. ‘For the Congress it would be fatal, because they would have failed in their primary objectives. I feel therefore that any circulation of the Bill involving long delays would be unjustified and possibly dangerous.’ Coming straight from the metaphoric horse’s mouth, it was a remarkably candid admission about the cause of the prime minister’s frenzied rush towards an amendment, and confirmation of the Opposition’s charge that the Constitution was being changed to suit the Congress party. Much like the president, the Speaker ultimately also found his objections curtly brushed aside.

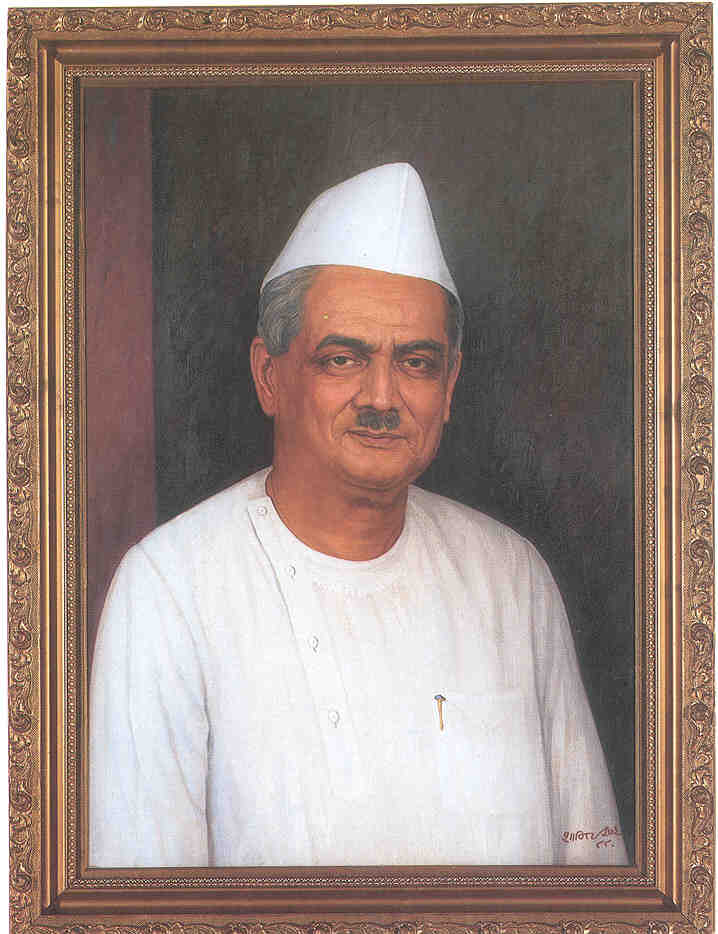

Speaker G.V. Mavalankar

Of the continuing parliamentary debate over 17 and 18 May, the Times of India reported:

Whatever of the Prime Minister’s imperative to Parliament to amend the Constitution survived the incisive logic of criticism yesterday was today well and nigh totally demolished by the formidable tide of argument that flowed from Congressmen and Independents alike, which not one supporter of the Bill was able to adequately answer.’

Despite supportive speeches from Congress leaders like Renuka Ray, Krishna Chandra Sharma and M.P. Mishra—who even contended that there was no need to elicit any public opinion because ‘no public opinion can be more weighty than the will of the Members of this Parliament’—Nehru was eviscerated by his opponents, who, according to press reports, ‘decimated the force’ of his arguments. Such opponents included not only independent members like H.N. Kunzru and Ramnarain Singh and Opposition figures like Hussain Imam, but also—to Nehru’s surprise and discomfiture—renegade Congressmen like Deshbandhu Gupta, H.V. Kamath and Syamnandan Sahay.

Kunzru declared that Articles 19 and 31 were not being amended, they were effectively being repealed, and if passed, the new article would extinguish freedom of speech and expression almost entirely. There was only one reason for this extraordinary course of events: the upcoming general election. H.V. Kamath suggested ‘that what needed amending was not the Constitution, but the policies of the Government’. The blanket validation of land reform legislation and the creation of the Ninth Schedule constituted, in his opinion, ‘nothing short of midsummer madness’. Hussain Imam described the amendment as ‘laying the foundations of an authoritarian state’ and Syamnandan Sahay thought it tragic that the Constitution was being reduced to the level of ordinary legislation. Deshbandhu Gupta charged the prime minister with showing little faith in the people of the country, who, according to the Preamble to the Constitution of India, more than any Parliament, had given themselves the Constitution as a charter of freedom.

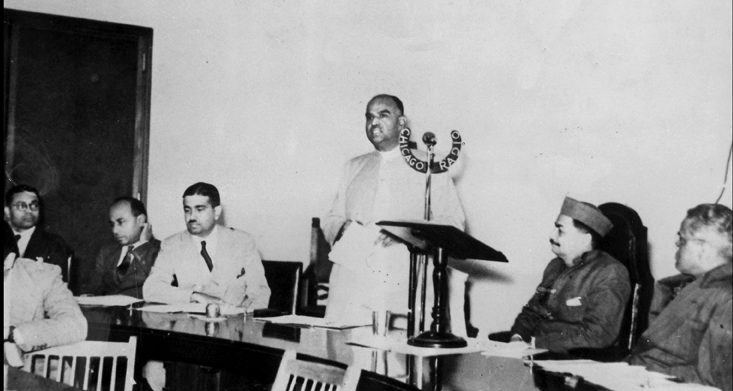

The government found itself struggling to answer the simplest questions: If they did not desire to use any of the enabling provisions of the amendment, then what was the hurry? If the Supreme Court hadn’t pronounced any verdict on zamindari abolition, where was the need to change the Constitution? Why was the government so keen to circumscribe freedom of expression? What was the imminent threat that Nehru kept referring to? Why were they so disinclined to set a positive example and create exemplary democratic traditions? Unable to face the heat, the government wheeled out Law Minister B.R. Ambedkar to mount a vigorous defence.

In a nearly two-hour-long speech, Ambedkar assured the House that the government did not intend to misuse any of the powers it was acquiring, and the amendment was only meant to arm Parliament with the power to pass certain legislation when necessary rather than enact any specific laws in the immediate future. He reiterated Nehru’s spiel that judicial pronouncements were ‘utterly unsatisfactory’ and not in consonance with the Constitution—especially the invalidation of the Communal GO and the policy of quotas—and that the government was committed to fulfilling its obligations as enumerated in the directive principles. New restrictions on free speech were necessitated by the refusal of the Supreme Court to interpret into the Constitution the doctrine of ‘inherent police powers’ like the United States, he argued. In order to secure itself from threats and fulfil its obligations, he maintained, it was vital that the Constitution be amended.

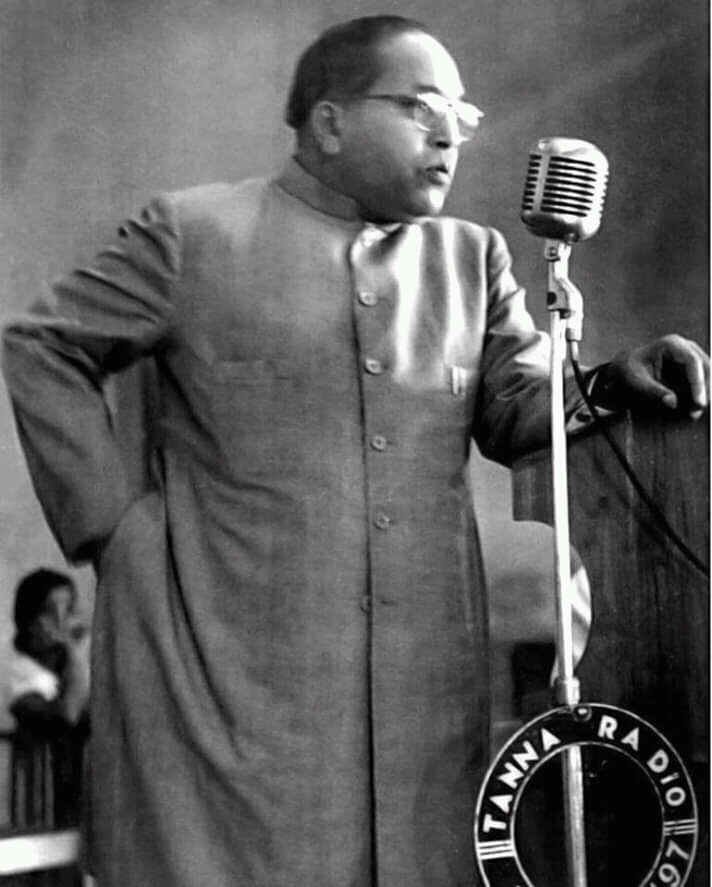

Law Minister Dr. Bhim Rao Ambedkar

Keen critics of the proposed Article 31B, which created the Ninth Schedule as a constitutional vault for land reform legislation, Naziruddin Ahmed, Syamnandan Sahay and H.V. Kamath questioned Ambedkar on the need for such an outrageous constitutional device to provide blanket protection to bad and possibly unconstitutional laws. ‘Just imagine the amount of burden that would be cast upon myself, on the Law Ministry, the Food and Agriculture Ministry and other Ministries involved if we were to sit here and examine every section of each of these Acts to find out whether they deviate,’ came Ambedkar’s terse reply. A more graphic revelation of the government’s unending search for short cuts and its apathetic and lackadaisical attitude would have been hard to find.

In his closing speech requesting MPs to refer the bill to the Select Committee, Nehru too spoke with fervour in defence of the amendment to Article 15 and continued to dwell on the confusion caused by the contrary judgments of the Allahabad and Patna High Courts—an obviously disingenuous turn of phrase. ‘This business of equality before the law,’ he exclaimed,

. . . [Is] a dangerous thing . . . and it is completely opposed to the whole structure and method of this Constitution and what is laid down in the Directive Principles . . . I am not changing the Constitution by an iota . . . I am merely giving effect to the real intentions of the framers of the Constitution and the wording of the Constitution.

An overwhelming majority of MPs did in the end vote to send the bill to the Select Committee, with instructions to report back on 23 May. Only two votes were cast against Nehru’s motion, demonstrating yet again the prime minister’s firm grip on the Congress Parliamentary Party. The measure clearly had the support of a substantial number of Congress MPs. But the ferocity of the debate, the equivocation from several Congressmen—particularly with regards to freedom of speech—and outright hostility from others, also brought home to Nehru that he was in for stormy days ahead, even if Congress MPs remained subservient for the moment.

The dramatic resignation of Acharya Kripalani from the Congress amid the ongoing parliamentary combat heightened this sense of tension. Declaring war on the government, Kripalani announced his intention to bring all Opposition forces into one fold. Some even speculated that another high-profile resignation from Communications Minister Rafi Ahmed Kidwai, a member of Kripalani’s dissident Democratic Front, could soon follow. Eventually, no such schism surfaced and Kidwai and other supposedly dissident members remained loyal to Nehru.

Acharya Kripalani

When the Congress Parliamentary Party met two days later, however, a formal motion to drop the proposed amendment to Article 19 was moved by Deshbandhu Gupta. It was easily defeated. But the fact that it was suggested and voted on at all was an unambiguous indication to the ‘high command’ that it could not rely blindly on the support of all its MPs; that many of them were getting restive about the assault on the freedom of speech and on the constitutional ideals that they themselves had helped shape. The unceasing criticism was also getting to Nehru. ‘I think much of the criticism is misconceived,’ he wrote to his chief ministers. ‘There is a strange fear in the minds of some that Parliament might misbehave and therefore should not have too much power given to it.’ None bothered to tell him that such a robust fear of excessive executive power was the bedrock of liberal democracy.

A twelve-member delegation of the All India Newspaper Editors Conference (AINEC) led by its president—the same renegade Congress MP Deshbandhu Gupta—also met the prime minister on 20 May to press its demand that the government drop the proposed amendments in the present circumstances or postpone it to a later date so that ‘public opinion may be fully elicited on the subject’. The doyens of the press were told by the prime minister that while the government was not prepared to meet either demand, it would nevertheless try to modify the amendment to try and mitigate their concern. Many wondered, was the unrelenting pressure forcing him to soften his stand? AINEC remained unconvinced.

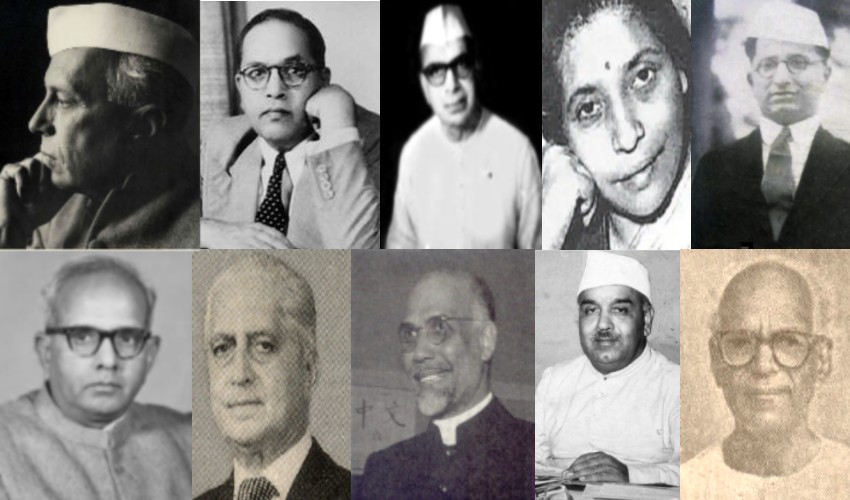

Supporting the First Amendment in Parliament: Top Row, Left to Right – Jawaharlal Nehru, B.R. Ambedkar, Seth Govind Das, Renuka Ray, Joachim Alva; Bottom Row, Left to Right – Tribhuvan Narayan Singh, Frank Anthony, Jerome D’Souza, Rafi Ahmed Kidwai, Krishna Chandra Sharma

From Parliament, the Constitution (First Amendment) Bill now made its way to the Select Committee. Much like Parliament itself, the Select Committee was dominated by the Congress party. Having weathered the torrid debate in the House, Congress members were confident of passing this hurdle with relative ease. Opposition leaders Syama Prasad Mookerjee, H.N. Kunzru, Sardar Hukam Singh, K.T. Shah and Naziruddin Ahmed, who made up a small but vocal and vociferous minority, were equally determined to mount a strenuous defence of fundamental rights and civil liberties. Both supporters and detractors of the bill now waited with breathless anticipation for the Select Committee’s report to appear and settled down to a brief interlude.

Meanwhile, outside the corridors of power, the emotionally charged debates in Parliament provoked an ever-growing torrent of adverse opinion. As the committee deliberated on the clauses of the amendment, vehement criticism from pressmen, businesses, lawyers, civil society groups and political figures alike continued to flood the pages of newspapers and the government’s undue haste and lack of respect for democratic propriety became a common topic of public discussion.

The Supreme Court Bar Association took the lead by denouncing the amendment and demanding that the executive function within the limits prescribed by the Constitution. Assembled lawyers appealed to all ‘public bodies who believe in civil liberties and particularly freedom of speech and expression’ to ‘mobilize public opinion and express themselves in unequivocal terms’. Following in its footsteps, the Nagpur High Court Bar Association ‘passed a resolution expressing its emphatic view that the proposed amendments were improper, unjustified, highly undemocratic and opposed to the fundamental rights of the citizens of India’. Former judges like N.C. Chatterjee of the Calcutta High Court and S.P. Sinha of the Allahabad High Court also inveighed against the measure and gave public statements castigating the government.

The Progressive Group, Bombay—a liberal organization consisting mostly of Muslims and Parsees—challenged the competence of a provisional parliament elected on a limited franchise and opposed any amendment of the Constitution before a general election. The All India Newspaper Editors Conference, unconvinced by Nehru’s assurances to its delegation, restated its demand for the complete withdrawal of the proposed amendment to Article 19 and the freedom of speech and expression. The Standing Committee of AINEC ‘placed on record its considered opinion that the proposed amendment (was) unwarranted and uncalled for, and hoped that the representations made by the President would persuade the Government to reconsider their attitude’.

Deshbandhu Gupta

Nehru, concerned at the reactions in the press, invited major editors and correspondents—Devadas Gandhi of Hindustan Times, Ramnath Goenka of the Indian Express and Shiva Rao of The Hindu—for a briefing with him. It did little to stem the tide of disapproval. In private correspondence, Deshbandhu Gupta informed the prime minister that his verbal assurances lacked any constitutional validity, and to give concrete form to them, suggested the inclusion of a new clause in the Constitution guaranteeing the freedom of the press—something akin to Article 1 of the American Constitution. ‘These wide powers [which the government was appropriating via the amendment],’ Gupta maintained, ‘were an open invitation to parliamentary majorities to abridge the freedom of the press.’ Nehru promptly rejected Gupta’s suggestions out of hand.

Left to Right: Ramnath Goenka of the Indian Express, Shiva Rao of The Hindu, Devadas Gandhi of Hindustan Times

In Kanpur, the tremendously well-respected elder statesman Sir Jwala Prasad Srivastava, former cabinet minister, former member of the Viceroy’s Executive Council and former member of the original Constituent Assembly, stated that the proposed amendments ‘were ill-timed, inept and ill-advised’ and warned that they ‘sought to take away the guarantees in the Constitution’. An interesting aside: Srivastava’s son-in-law Minocher ‘Minoo’ Masani would one day found the Swatantra Party and become one of Nehru’s fiercest critics, leading the liberal fightback against Congress dominance.

Sir Jwala Prasad Srivastava

Within the fourth estate, reactions to an amendment that placed ‘the press literally at the mercy of bureaucratic whims’ were universally condemnatory and vituperative, with open declarations that the ‘press will and must organize its resources to fight this encroachment on fundamental freedoms.’

One writer railed:

Public order is the foundation of a stable state. But to empower governments with the expansive right to abridge freedom of expression in matters pertaining to public order is surely to strike at the roots of democratic rule and life . . . Tomorrow a communist government under cover of the proposed amendment to restrict free comment on foreign affairs might dragoon the press into bowing to the behests of the Kremlin . . . In the name of public order a dictatorial administration . . . may scotch all opposition to itself by a blanket ban on criticism against the Government on the ground that this is likely to undermine public order. These are the dangers to democracy and democratic rule inherent in the new amendments.

‘The whirling of time has indeed brought forth its revenges’ mused another senior commentator.

Those who in former times championed most vociferously freedom of speech and expression, having now settled down in the seats of power, see no incongruity in themselves proposing to impose more rigid restrictions upon them. Clearly they show no understanding of the nature of freedom.

‘If further restrictions are to be imposed’ he asked the government,

[It] must surely be shown that because of the absence of these restrictions our friendly relations with foreign governments have been imperilled, public order has been endangered and there has been widespread incitement to offences. So far as one can make out from the debates, there has been no attempt to show that throughout the country conditions have been such as to necessitate these changes. All we find is mention of a few judicial pronouncements—occasionally even judicial obiter dicta—from which it is argued that the changes are necessary.

Without the amendments of Articles 15 and 31, ‘certain inconveniences will undoubtedly be caused to the party in power, certain policies sponsored by the party will not show all the results expected from them, and this may cause the electorate in certain areas to be not too enthusiastic in its support,’ he argued. ‘But surely these furnish no reasons for forcing through fundamental changes . . .’

The legal correspondent for the Times of India accused Law Minister Ambedkar of trying to be too clever by half in censuring the Supreme Court for refusing to support his doctrine of ‘implied police powers’ and published long extracts of his speeches to the Constituent Assembly in 1948 to demonstrate how he had gone back on his own claims. In 1948, Ambedkar had categorically asserted before the Constituent Assembly that instead of formulating fundamental rights in absolute terms and depending on the Supreme Court to invent the doctrine of ‘police powers’ and read limitations into them (as happened in the United States), they were going to directly write such restrictions into the Constitution itself, forestalling the need or the ability of the Supreme Court to invent any doctrines. Having made such a statement in the Constituent Assembly, in the correspondent’s opinion, for the law minister to now demand ‘implied police powers’ was nothing short of dishonesty.

‘In supporting the Constitution (First Amendment) Bill the prime minister stated, inter alia, “it was not to be used by the present Government but will be handed down as a legacy to future parliaments,” wrote an irate citizen from Bombay in a letter to a major newspaper. ‘Then what is the necessity of introducing it in the present Parliament? If, as Mr Nehru admits, “nothing could be static or unchanging” and the situation may alter radically, it is hardly fair to act presumptuously towards the next Parliament.’

The spate of criticism and adverse opinion, incessant and implacable, momentarily shook the prime minister. Within the Select Committee, he came under increasing pressure on the issue of freedom of speech and expression, on which a growing number of Congressmen disagreed with him. Many supporters pressed him to include the phrase ‘reasonable restrictions’ to allow any of the restrictions placed to be justiciable rather than grant the government blanket and arbitrary powers to curb free speech and completely exclude any possibility of judicial review. Nehru, who self-confessedly wanted to circumscribe the judiciary’s power and show the judges their place in the pecking order, recoiled at this advice.

‘I confess I do not like the word “restriction” or “reasonable” added to it,’ he wrote to T.T. Krishnamachari, Congress MP from Madras and former member of the Drafting Committee in the Constituent Assembly.

So far as I can see, the courts have always had the right to consider any legislation . . . It is true that if this amendment is passed, they will be somewhat restricted in their interpretation. But I feel that putting in the word “reasonable” would be an invitation for every such case to go to the courts with ensuing uncertainty.

In the prime minister’s own words, he did not want the restrictions on the freedom of speech to need to pass any test of reasonableness. He wanted to exclude the courts from adjudicating on them altogether. The word or the idea of restrictions may not have appealed to him very much, but the idea of them being reasonable appealed to him even less. It was a strangely contradictory position to take: to dislike restrictions but want them to be overarching and non-justiciable when written into the Constitution. Between the fundamental rights of the country’s citizens and the prime minister’s single-minded devotion to remaking India in his own image, the latter was the undeniable victor.

The Select Committee finished its deliberations on the evening of 22 May 1951. By Nehru’s own account, Opposition figures forced extensive discussions on every single issue, often compelling the committee to meet both in the morning and in the afternoon to complete its work. Article 19 and the freedom of speech remained a major bone of contention. ‘I feel quite exhausted,’ the prime minister confessed at the end of four days of deliberations.

Outside, the storm of criticism refused to abate. Under fire from the press, the commentariat and the Opposition, large numbers of Congress MPs began to vacillate on the extent of their support for Nehru’s line, particularly the attack on Article 19. When the Congress Parliamentary Party met on 23 May to take stock of the situation, the prime minister was presented with a petition signed by seventy-seven MPs asking for a free vote when the amendment was discussed in Parliament. Nehru was taken aback by the move and surprised by the rapid slide in support. From a near-unanimous majority for the amendment to Article 19 in the meeting on 20 May to the demand for a free vote on 23 May, the deterioration in the party’s mood was swift and, for Nehru, dangerous.

Opposing the First Amendment in Parliament: Top Row, Left to Right – Hriday Nath Kunzru, Sardar Hukam Singh, Sucheta Kripalani, H.V Kamath; Bottom Row, Left to Right – Jaipal Singh, Acharya Kripalani, Shibban Lal Saxena, Syama Prasad Mookerjee

The prime minister sensed the precariousness of the situation. The party might have been in his thrall and there may not have been any open rebellion, but there were enough doubters and dissidents to deny him his victory over the Constitution if he did not moderate his stand. By the time the Union Cabinet met in the evening, Nehru was already under significant pressure from rebellious MPs and probably mulling his options. Within the Cabinet, several ministers now started to insist that the word ‘reasonable’ be included in the amending bill to safeguard judicial oversight of restrictions on fundamental rights. Many perhaps realized that without it, the amendment constituted a near-existential threat to Part III of the Constitution. Support for Nehru’s draconian vision of emasculating the courts was now fading at an alarming rate.

The surprising turn of events shocked the prime minister and convinced him of the need to pedal back. It brought home the limits to which both the Cabinet and the Congress Parliamentary Party were willing to obey his diktats. Hemmed in on the issue, Nehru conceded ground and accepted the inclusion of the word ‘reasonable’ in order to prevent a split in the Cabinet and ensure that there were fewer avenues for internal dissent when trying to muster a two-thirds majority. ‘The cabinet is understood to have decided to meet the mounting criticism against the proposed amendment to Article 19(2) of the Constitution, relating to “restrictions” on the freedom of speech and expression by accepting a modification that will render it justiciable,’ reported a correspondent. ‘The clause in question is to be amended by limiting to “reasonable restrictions” the proposed unfettered right of the State to impose restrictions in the interests of public order and maintaining friendly relations with foreign states.’

It was a very limited concession, extracted much against the prime minister’s own will and volition. But it served to dilute the absolute worst part of the proposed amendment and placate the agitated members of the Cabinet. Whatever restrictions the government might legislate on the right to freedom of speech, they would have to submit to a judicial determination of their reasonableness. The unrestrained ability of the state to curtail fundamental rights, the most extreme of Nehru’s ideas, was negated. Unbeknownst to the participants in that momentous Cabinet meeting, their rearguard action had just warded off one of the gravest threats the Constitution ever faced, or was likely to face in the future. A handful of doubters and dissenters, having built up the conviction to stand up to a larger-than-life prime minister that towered over them in the public eye, had just saved the foundations of Indian democracy and its constitutional order.

Whether the concession would be enough to mollify restive Congress parliamentarians, of course, was another question altogether. The sobering experiences of 23 May left Nehru unsettled and disturbed. Could he rely on his MPs to fall in line behind him as in the past? Suddenly he was not so sure. ‘You can have no idea whatever of the tremendous difficulties we have had with this Bill and we are not out of the woods yet,’ he confided to West Bengal chief minister Bidhan Chandra Roy. ‘Till the last moment I shall not know whether we can have the requisite two-thirds number for passing these clauses.’

While the effects of the concession on the Congress Parliamentary Party remained a matter of conjecture, it distinctly failed to impress the doyens of the press. Now decidedly nervous, the All India Newspaper Editors Conference resolved to hold a special plenary session ‘to consider the steps which should be taken to protect the liberties of the press now threatened by the proposed amendment to Article 19(2) of the Constitution’. In an attempt to embarrass Nehru into reconsidering his stance, correspondence between Deshbandhu Gupta and the prime minister was made public. It had little effect.

On the question of reservations and Article 15, however, there was much more consensus within the Cabinet. Insistent requests had continued to pour in from Madras arguing that the proposed alteration of Article 15 was insufficient to protect reservations for the backwards and ‘hence a new clause should be added to the article to the effect that nothing in the article or in Article 29(2) should prevent special provisions for the educational, economic, and social advancement of the backward classes.’ Cabinet ministers, and Congress members in the Select Committee, accepted this demand to bring Article 29—which prohibited discrimination in admissions to schools and colleges—into the ambit of the amending bill. They were now of the view ‘that this provision is not likely to be, and indeed cannot be, misused by any government for perpetuating any class discrimination against the spirit of the Constitution, or for treating non-backward classes as backward for the purpose of conferring privileges on them’.

In a new twist, they also recommended that all references to ‘economic’ and ‘economically’ be dropped and the language be limited to ‘socially and educationally backward classes’. Through this sleight of hand, the cabinet sought to achieve two objectives. First, it would remove any prospect of economic criteria coming in the way of calculating the backwardness of a class based on their ‘social and educational’ standing. Second, it would pre-empt and negate any demands for special provisions or reservations for those who could be termed economically backward without the corresponding status of social or educational backwardness. In other words, they wanted to acquire the power to legislate for caste- and community-based reservations—what the Constitution scholar Granville Austin called ‘compensatory discrimination’— while preventing the creation of any affirmative action mechanisms based on economic criteria.

The exclusion of economic backwardness from the ambit of India’s reservation and affirmative action policies—either as a test for community-based reservations or as a criterion in and of its own accord—would open up a new political fault line that has endured to this day. Today, the debate around this fault line is expressed either in terms of demands for reservation for ‘economically weaker sections’ among the forward castes or demands for exclusion of the ‘creamy layer’ in reservations for Other Backward Classes. But few recall just where the race to social backwardness first began. Much before V.P. Singh and Mandal in 1990, much before the ninety-third amendment and Arjun Singh in 2006, it was in this dimly remembered cabinet meeting that the constitutional groundwork for this debate was first laid.

President Rajendra Prasad, who had been keeping a close eye on proceedings as the debate raged in Parliament and outside, now made a final, eleventh-hour effort to persuade the government to abandon the reckless course it had set itself on. In a note to the prime minister, Prasad reminded him of his view that the amendment was ‘premature and uncalled for’, and of the need to lead by example by establishing good conventions. He again cautioned Nehru against an attempt to overrule judicial pronouncements through a constitutional amendment, admonishing him that it would raise fundamental issues related to the separate functions of the legislature and the judiciary. Nehru, already irritated by what he thought was Rajendra Prasad’s propensity to exceed his brief, was incensed.

‘As you are aware, the Bill for the amendment of the Constitution has been discussed with great thoroughness both in Parliament and the Select Committee, as well as in the Press and by the outside public,’ came the prime minister’s terse response to the substance of the President’s objections.

Before the Bill took shape, the matter was considered by a subcommittee of the Cabinet and a committee appointed by the Congress party in the Parliament. The two committees held consultations together. We consulted also eminent lawyers, including the Attorney-General and Shri Alladi Krishnaswamy Aiyyar. Both of them were clearly of the opinion that it was within the competence of Parliament to consider and pass this measure . . . After this very full consideration of this subject from every point of view, the Cabinet have come to certain firm conclusions, which are now embodied in the Select Committee’s report . . . The Government is convinced of the necessity as well as the validity of the amendments proposed.

‘It would be exceedingly unfortunate if the public became aware that the President held a contrary opinion to that of the Cabinet in such a matter and was pressing for its adoption by the Cabinet,’ he reprimanded Rajendra Prasad. ‘I shall certainly place your note before the Cabinet as desired by you . . . I do not propose to circulate this for fear of leakage and undesirable publicity. I trust also that your office has not sent copies of this note to anyone else.’ For the second time, the president of the republic found his advice spurned and his views treated as unworthy of serious consideration. Committed to the constitutional order and the maintenance of decorum, Rajendra Prasad, despite his strong feelings on the matter, followed Nehru’s advice and scrupulously avoided publicizing his opposition.

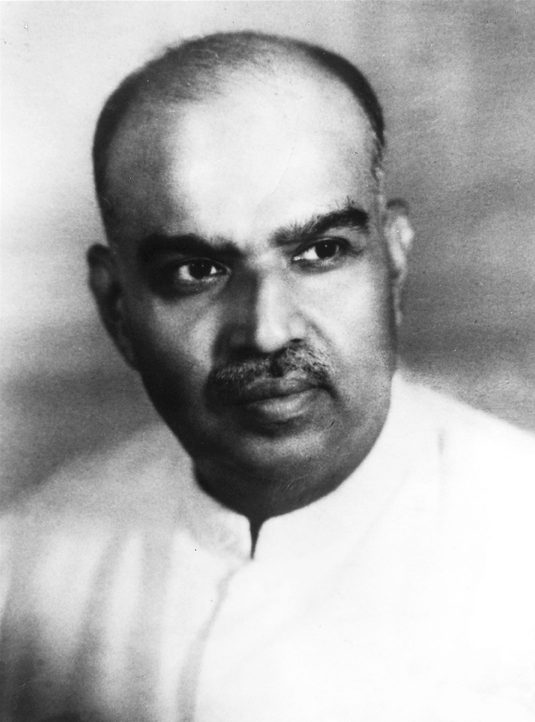

Dr. Syama Prasad Mookerjee

On 25 May 1951, the new draft of the Constitution (First Amendment) Bill emerged from the Select Committee. Along with the draft, the report from the Select Committee was submitted to Parliament the same morning. After several days of intense deliberations, the twenty-one members produced an eighteen-page-long report. Recommendations from the committee took two pages; scathing minutes of dissent by Opposition members filled sixteen. As the press prominently noted, ‘All the five non-Congress members of the committee recorded minutes of dissent, some of them including Dr. Syama Prasad Mookerjee and Pandit Hriday Nath Kunzru doubting the very advisability of amending the Constitution in such haste after it had been in operation for only sixteen months.’

In his minute of dissent, S.P. Mookerjee strongly questioned the need for any further restrictions on the freedom of speech and expression. ‘The onus of proving the need for changes has not been satisfactorily discharged,’ he argued. ‘The main reason advanced was that the judiciary had pronounced its opinion on certain laws which were disfavoured by the government.’ ‘The existing restrictions on the right to free speech and expression were more than sufficiently restrictive and there should be no fresh additions to these restrictions,’ he urged, and ‘the word public order must be subject to the “clear and present danger” test, namely that the substantive evil must be extremely serious and the degree of imminence extremely high.’ ‘Nothing has as of yet happened to justify the taking away of the jurisdiction of the judiciary in this sweeping manner,’ he wrote, castigating the government for its scramble to amend Article 31 and create a schedule of unconstitutional laws. ‘Instead of amending the lawless laws and making their provisions consistent with fundamental rights, the Government are following a strange procedure of adhering to such reactionary laws and changing the fundamental rights.’

‘Restrictions like the pre-censorship of news and the banning of the entry of a newspaper into a state were imposed during the war under the Defence of India Rules,’ read the excoriating observations of H.N. Kunzru, challenging the Congress to explain ‘why the Government in a free India should be allowed to exercise such powers as were not exercised even during the British regime in peacetime’. Turning his attention to the revalidation of Sections 124A and 153A of the Indian Penal Code—sedition and causing enmity between groups respectively—Kunzru wrote: ‘The history of Section 124A is well known. It was passed in its present form in 1818 to curb the activities of Indian patriots . . . Now that India is free, it should find no place in a statute book in its existing form.’

K.T. Shah, Sardar Hukam Singh and Naziruddin Ahmed produced a joint minute of dissent asserting their opinion ‘that the experience gained under the Constitution was insufficient to justify an amendment, they did not have the texts of the laws to be validated [laws that would be placed in the Ninth Schedule] and there was no evidence at all to justify this wholly gratuitous and unwarranted restriction on civil liberties’. ‘We have grave doubts and misgivings as to the wisdom, propriety and justification of the Bill,’ the trio concluded, flagging their reluctance to support the government’s invasion of individual freedom.

In the new democratic republic, however, the views of the Opposition, no matter how well reasoned or how well intentioned, counted for little in the eyes of the country’s new regime. Opposition leaders, much like the president and the Speaker, found themselves sidelined and their views treated with indifference and scorn. This was to become a norm. In this new Nehruvian India, ‘there were numerous committees and consultation was frequent,’ wrote Sarvepalli Gopal, ‘ . . . the deficiency was in spirit and animation.’

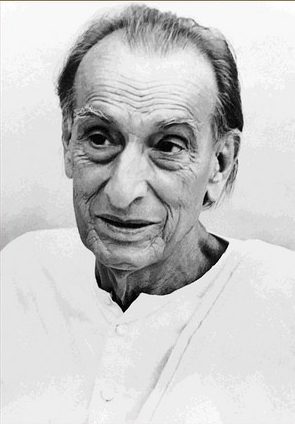

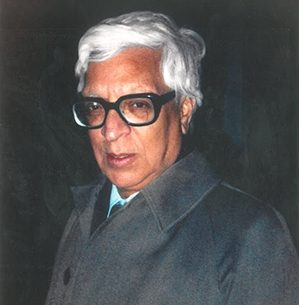

Sarvepalli Gopal

If ever more evidence was needed, the Select Committee report convincingly demonstrated the complete and utter lack of consensus on the matter and the absence of any respect for the Opposition’s views. There was little doubt left that the amendment of the Constitution was a Congress project driven by the prime minister with no support from Opposition figures—not even from those who conceded the principles of land reform and affirmative action.

Despite the passionate arguments put forward by Opposition figures, the majority of the Select Committee felt otherwise. Fervent appeals to Nehru’s sense of democratic propriety and the need for the ‘provisional parliament’ to show moral uprightness by waiting for a general election fell on deaf ears. All warnings that a dangerous precedent was being created went unheeded. The only major changes the committee recommended were the use of the word ‘reasonable’ before restrictions to make justiciable any legislation on the subject in respect of Article 19, a limitation of the language to ‘socially and educationally backward’ and the removal of all reference to economic backwardness, and the inclusion of Article 29(2) within the ambit of the qualification to be added to Article 15. In all other respects, including the alteration of Article 31 and the creation of the hugely controversial Ninth Schedule, the committee ignored the intense resistance of the Opposition and placed its stamp of approval on the bill drafted by the government.

Newspapers had been optimistically speculating on the concessions that Nehru might agree to in a bid to propitiate his critics and assuage his restive MPs. The recommendations of the Select Committee left them disappointed and angry. ‘Except for a grudging concession to the press and certain other modifications for elucidating other provisions the Bill to amend the Constitution has emerged unscathed from the 21 member Select Committee,’ lamented a report in a major newspaper. Having ruminated on the changes suggested by the committee for several days, another correspondent reaffirmed the stand of the press by stating that ‘the so-called concessions to popular demand are no adequate substitutes for existing safeguards’.

In a muscular editorial evocatively titled ‘Not Enough’, the Times of India contended that phrases such as ‘reasonable restrictions’, meant to be safeguards against the heavy hand of the government ‘can at best constitute only a partial check on the executive’s abuse of powers. Experience shows that terms such as “reasonable compensation” can carry a multitude of meanings. Moreover, those who may be victims of the new repressive laws are not always likely to have the means to seek legal redress.’ ‘A more pernicious feature of the new amendment is that the scope of the permitted restrictions remains as wide as the original draft,’ raged the writer. ‘As for the new restrictions allowed in the sacred name of public order, these can only help unscrupulous regimes to identify their own safety with the “security of the state” and to stifle all organized protest.’

‘Why are “economically backward” people less deserving of help than “socially and educationally backward classes”?’ the editorial fumed. ‘As for securing special rights for Backward Classes, Clause 4 of Article 15 as redrafted does not prevent the treating of non-Backward Classes as Backward for the purpose of privileges on them.’ Positively seething, the writer of the editorial warned Nehru: ‘At the root of democratic progress is the belief that the heterodoxies of today may become the orthodoxies of tomorrow and that the opposition of today may in the course of time achieve the majesty of government.’ It was a warning that was apocalyptic and oracular in equal measure. Nearly seventy years on, facing the full force of the amendment, the Congress party, Nehru’s ideological descendants and co-travellers, and the one-time cheerleaders of the Nehruvian offensive, live on to testify to the veracity of the unknown writer’s prophetic warning.

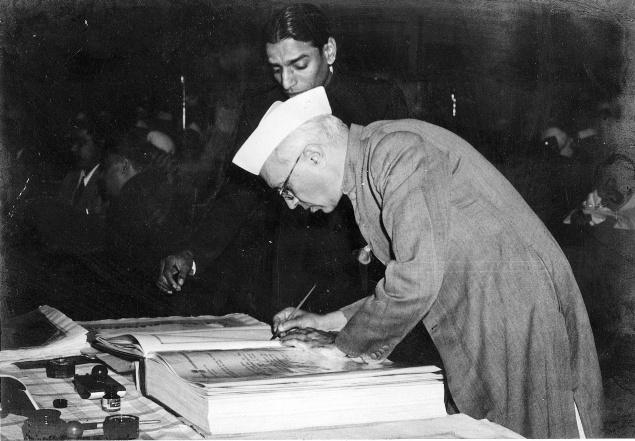

Jawaharlal Nehru signing the Constitution of India

Nevertheless, at that moment in May 1951, so far-fetched did the possibility of the Opposition achieving the majesty of government seem that none bothered to take it seriously. Small in number, limited in electoral appeal and lacking any party organization, the threat of the Opposition one day using Nehru’s own stick to beat him with carried near-negligible weight as a deterrent. But what the Opposition lacked in numbers and electoral appeal, it made up for in its strength of purpose and its dedication to the defence of the Constitution. Having failed to convince the government to heed their opinions in the Select Committee, Opposition leaders now prepared to make a last ditch stand in Parliament.

‘The Opposition’ noted one journalist,

[M]ay be numerically small in view of a strong Congress Party whip, and many doubters have certainly been satisfied by the change rendering justiciable the restrictions that might be imposed on freedom of speech and expression. But for all that, the Opposition will be intense and will probably be speaking for more than those who might care to walk out of the “noes” lobby . . . Members of the former Democratic Front [Kripalani’s group of dissident Congressmen] have taken counsel together on this measure . . . they are expected to oppose tooth and nail the very principle of a constitutional amendment at this stage.

As the amendment bill and the debate around it moved inexorably towards a conclusion, Opposition figures from across the political spectrum, few and far between as they were, now braced themselves and prepared for a fateful parliamentary confrontation. Much like the warriors of yore, woefully outnumbered and comprehensively outgunned, these intrepid defenders of constitutional freedoms unsheathed their verbal swords and rode out to battle.

The battle was joined on 29 May 1951 as Prime Minister Nehru moved the bill as amended by the Select Committee for Parliament’s consideration. Even before Nehru began speaking, he was interrupted by H.V. Kamath objecting to the ‘vitiated’ proceedings in the Select Committee. He was quickly shouted down by the Speaker to allow Nehru to begin proceedings. The mood was sombre—this time, there would be no niceties.

‘We live in a haunted age,’ Nehru informed his colleagues.

I do not know how many members have this sense . . . of ghosts and apparitions surrounding us, ideas, passions, hatred, violence, preparations for war, many things you cannot grip, nevertheless which are more dangerous than other things . . . Hon. Members tell me that this Constitution has been in existence for sixteen months. Can any member tell me what the fate of the world will be in another sixteen months?

The apocalyptic imagery was fitting.

In his seventy-minute address, the prime minister justified the amendments to Article 19 by vague allusions to a grave danger to the state and repeated the allegation that fundamental rights were now an obsolete idea. The addition of the word ‘reasonable’ made anything done under the act patently justiciable, he continued, and admitted that they had avoided using that word earlier ‘to avoid an excess of litigation about every matter, everything being held up and hundreds, maybe thousands, of references constantly made by odd individuals or odd groups thereby holding up the work of the state.’

The brazen admission by the prime minister that he considered individuals fighting for their constitutional rights to be odd and had wanted to prevent them from knocking on the doors of the judiciary provoked an indignant reaction from H.V. Kamath about the sacrosanct nature of fundamental rights. Nehru remained unfazed. ‘I wish the House would be clear about this and realize the times we live in,’ he sneered, ‘in this country and other countries, and not to quote so much some ancient script or ancient thing that was said at the time of the French Revolution or the American Revolution. Many things have happened since then.’

‘It is not merely a question of what words you put in the Constitution’ he glowered.

It is a question of dealing with the situation . . . of saving the country from going to pieces, as some people want and try to make it . . . Are we going to fight it with these words, to be told that this word comes in the way and that word prevents you from doing this? No word will be allowed to come in the way because the country demands it . . . Do you think any Constitution will prevent me from dealing with such a situation? No. Otherwise the whole Constitution goes . . . I want to be perfectly clear in declaring that if I am responsible and this Government is responsible, anything that goes towards disrupting the community . . . will be met with the heavy hand of the Government. There has been enough loose talk about this. It is for this country and this House to have or not to have this Government. But these are the terms of this Government, no other terms.

If the exposition of his repressive and absolutist vision for the new republic needed further elaboration, Nehru proceeded to delineate it while giving the press a piece of his mind. ‘I know something of the press, and I have been connected with the Press too somewhat, and can understand their apprehensions,’ he insisted.

Yet I say that what they have said is entirely unfair to this Government. And I say that the Press, if it wants that freedom— which it ought to have—must also have some balance of mind which it seldom possesses. They cannot have it both ways—no balance and freedom. Every freedom in the world is limited.

As for why the government had included relations with foreign states as a ground to restrict fundamental rights, Nehru’s reasoning was equally outlandish. He only wanted to cover incitement to war and defamation of foreign heads of state, he claimed, but it was phrased to say friendly relations with foreign states because it was a friendly way of saying this and nice from the literary point of view. Exactly what amounted to a danger to friendly relations with foreign states, as usual, Nehru declined to specify. None bothered to point out that constitutional provisions were unlikely to be judged on literary merit. But the grim prognosis of the heavy hand of government and the limits of freedom evoked lusty cheers from Congress MPs.

The prime minister mounted a spirited defence of the amendment to Article 15, which he contended, had been necessitated by the events in Madras. ‘The argument of the Courts was valid from one point of view,’ he contended, ‘namely that communities as such could not be discriminated against. But for a variety of historical reasons, all manner of socially, educationally and economically backward classes existed and in order to encourage their progress ‘something special’ had to be done for them.’

Syama Prasad Mookerjee, 1978 stamp of India

‘Some apprehensions had been expressed that this amendment might be used to perpetuate class discrimination,’ reported an eyewitness, ‘but Mr Nehru assured the House, this power would not be misused.’ Some critics such as K.T. Shah and H.V. Kamath had pointed out that 80 percent of the people were backward in those terms, regardless of their caste or community. Any special provisions should thus cater for all of them. ‘It is no good saying that,’ Nehru replied disdainfully.

Much of this was, of course, a reiteration of what the Prime Minister had previously argued—an elaboration of his views and an outline of his perspective on democracy. They were the standard tropes: the Constitution needed to be flexible and follow the curves of life; it could not be allowed to ossify around ancient slogans from the French Revolution and archaic ideas about fundamental rights; the press and his critics were out of control and needed to be disciplined; the Constitution could not be allowed to come in the way of the Congress manifesto; the judiciary was overreaching itself by preventing the government from ignoring the Constitution and doing whatever it wanted to, which of course was obviously for the security of the nation. It was the most articulate depiction of the premises that underpinned Nehru’s conception of the democratic state, premises that progressively became principles of the new post-colonial order.

Opposition leaders K.T. Shah and Naziruddin Ahmed, who were the next to speak, both ripped into Nehru’s contention. ‘Prof. K.T. Shah threw ridicule on this (the PM’s) argument by stating that the Constitution already made adequate provision for grave emergencies,’ reported a newspaper. ‘By a declaration of emergency, the President could suspend the entire Constitution and Government would be armed with unfettered power to take any measure that might be necessary.’ Naziruddin Ahmed maintained that if any laws had been invalidated,

[T]he fault lay not with the Courts, which had interpreted the Constitution correctly, but with the Government, who had failed to adapt such laws as was enjoined upon them by Article 372 of the Constitution . . . (much) as the British Government had adapted a whole series of enactments to the 1935 Act by a single consolidated measure.

The gods now decided it was their turn to communicate their displeasure. Claps of thunder rolled across the sky. As Naziruddin Ahmed savaged the amending bill, a sudden thunderstorm broke over the national capital. ‘The gale and accompanying thunder showers came upon New Delhi so suddenly,’ reported the Times of India, that even before windows and skylights could be closed, many MPs on the Congress benches were drenched in the rain. On a more portentous note, power went out and the lighting inside Parliament failed, plunging the chamber into gloom.

The darkness was an unmistakable omen for the new republic, a moment of delicious irony. ‘Freedom of Speech is being taken away,’ remarked H.V. Kamath to general guffaws, ‘and there is a storm over it.’

As the debate over taking the bill into consideration played out over 30 and 31 May, Parliament witnessed a fierce war of words on the subject as a spirited Opposition continued to confront the government. ‘As an obvious result of yesterday’s party whip, Congress members abandoned all criticism in the House and this only brought into sharp relief whatever opposition came from independent members,’ noted The Statesman. Having weathered tremendous criticism, several proponents of the amendment were pressed into service to give speeches supporting the government’s stand. Yet, even here, support was either lukewarm or often driven by ulterior motives or general frustration.

Reverend Jerome D’Souza, Congressman and Jesuit priest, was enthusiastic about the restoration of the Madras Communal GO because it was impossible to overlook the fact of backwardness, but he was more concerned with extending caste-based reservations for Christians so that socially backward classes could freely convert to Christianity without losing their backward status. He wanted race and culture as well as caste and community to be recognized to determine such backwardness, but insisted that religious differences should be ignored, presaging the modern demand for recognition of Schedule Caste and Backward Class Christians. As for freedom of speech as given and practised in England, he professed his condescending belief that since Indians did not possess the ‘phlegmatic’ English character distinguished by its stolidity and balance, it was necessary to restrain the organs of public opinion. The statement was greeted by widespread cheering across the treasury benches.

The famous Anglo-Indian educationist Frank Anthony, venting his frustration over the conundrum the bill represented, declared that he was not ‘prepared to accept the argument that these amendments are only an amplification, a clarification . . . They are a revolutionary, radical change in the original Article 19(2).’ ‘The only way to stop the inevitable, ultimate dictatorship, communist dictatorship is a dictatorship of Jawaharlal Nehru,’ he lamented. ‘But because I believe that a dictatorship today is the only way to prevent a later dictatorship, I am prepared to give blanket powers to Jawaharlal Nehru. That is my only reason for supporting these amendments completely.’

Our leaders are incapable of thinking and practising in terms of democracy,’ he continued with his complaint. ‘The British occupation taught us . . . respect for the forms and trappings of democracy but the spirit and content of democracy have escaped the people and they have escaped our leaders . . . If the Constitution is largely dead, if it is largely still-born, why worry about making an excision?

On the Opposition side, the charge was led by Syama Prasad Mookerjee and Acharya Kripalani.

Mookerjee reminded the House that they had deliberately chosen a written Constitution incorporating a chapter on fundamental rights. They could well have decided not to create a chapter on fundamental rights in writing, but having done so, they necessarily had to admit the corollary that their powers to legislate on such matters were limited by the Constitution they themselves had created. Fundamental rights ‘were so many checks on the hasty and tyrannical action of the majority and served to protect the liberty of individuals and minorities,’ he stressed. ‘And if fundamental rights were enumerated in writing, that was in order to withdraw them from the arena of political controversy.’ ‘You cannot pass or amend a Constitution to fight with ghosts,’ he warned Nehru, likening him to the Prince of Denmark fighting imaginary troubles in Shakespeare’s Hamlet.

Syama Prasad Mookerjee

In spite of the opponents of the bill being in a minority, Mookerjee argued vehemently against the revalidation of repressive laws originally created to stifle Indian freedom under colonial rule, warning that they were ‘sounding the death-knell of democracy’. ‘We are giving more powers to Parliament to enact more laws restricting freedom,’ he censured his colleagues. ‘I submit that this is a completely wrong approach to the problem.’ ‘But in any case,’ he remonstrated with the government, ‘the power which you are now taking is not power which is necessary for any emergency that has arisen in the country, but for perpetuating certain lawless laws which our British masters had forged for the purpose of curbing freedom in India. That is what we are doing.’

‘Let me exhort and conjure you never to suffer an invasion of your political constitution, however minute the instance may appear, to pass by without a determined persevering resistance,’ he fervently entreated the House, quoting the Letters of Junius, a tranche of open letters written by an anonymous eighteenth century British polemicist critical of King George III. ‘They soon accumulate and constitute law. What yesterday was fact, today is doctrine.’

Acharya Kripalani, veteran Gandhian, erstwhile Congress president and a leading light of the struggle for independence, was vitriolic in upbraiding the government. The country was pledged to zamindari abolition, he argued, and the population’s views on the subject were well known. It was perfectly reasonable to change the Constitution to effect this, ‘but the country was also solemnly pledged to the freedom of speech and expression, especially in light of the restrictions imposed on these freedoms by an alien government. Yet these freedoms were now to be abridged.’ Public order and incitement to offence were undefinable terms, the Acharya opined. Satyagraha was an offence, all processions and demonstrations disturbed public order. Were all these to be stopped by using the might of the state against its own citizens?

There were no replies. Kripalani, one of Gandhi’s most ardent disciples, spoke slowly and with a bite to his voice, relishing the opportunity to take his former party apart. Sidelined, ignored and humiliated by his one-time colleagues, he now laid into them with bitter acerbity. The chamber, which had emptied out as Congress leaders dutifully extolled the virtues of the amendment, rapidly began to fill as Kripalani continued. ‘It is superfluous to speak at this stage. Government seem to have made up their mind and they have a solid majority behind them; whatever is proposed will be carried out,’ he acknowledged with unsentimental frankness. ‘But sometimes, it becomes one’s duty to raise a voice of protest when things that we never imagined before are done.’

‘We are accused of being idol worshippers,’ he claimed. ‘By whom are we accused? I am sure the greatest beneficiary of this idol worship is our Prime Minister and also, may I add, his government. But for this idol worship this government would have fallen at least twenty times during the course of the last three years.’ ‘I know from experience that when people who are weak are given power, they use their power to their own injury,’ he apprised the prime minister, his voice gleaming with glacial sarcasm.

A government that cannot dismiss a peon in office wants to clothe itself with extraordinary powers! I submit, these extraordinary powers will be used to your injury; and who will use them? It will be they that will come after you. You are not going to be eternal. No government is going to be eternal . . . More power will only injure you. So please be satisfied with limited power, because your capacity is very limited indeed.

Meanwhile, outside Parliament, political observers, commentators and ordinary citizens alike continued to fulminate against the government and the prime minister. ‘Mr Nehru’s apologia for the Constitution Amendment Bill as it emerged from the Select Committee fails to convince,’ wrote the Times of India, ‘ . . . the prime minister urged that a Constitution has to be flexible and move with and adapt itself to the curves of life. If Governmental reactions to the Constitution could be traced in a graph, they would be more curvaceous than a scenic railway.’ ‘We might be living in the arid days of the tired thirties,’ it snidely remarked, ‘when foreign bureaucrats spoke thus to the representatives of the people.’

Another commentator tartly observed:

How can we have a straight, stiff, stable constitution, eternally hugging the dead distant slogans of obsolete revolutions—Liberty, Equality, Fraternity, Justice—the crude claptrap with which politicians create imaginary utopias? . . . It is good to be reminded now and then in the midst of canting moral and political platitudes that our life and the Constitution which moulds it are of such insubstantial and delusive stuff.

‘Though in the interests of the Fundamental Rights, the Constitution itself cannot be taken as sacrosanct,’ reasoned an angry citizen in a letter to the newspaper, ‘legislation by a constant clash with the Constitution should not render it chimerical by passing amendments to suit the purposes of the administration. Any attempt to recast the Constitution with the needs of the Government would be a mockery of democracy.’

In Lucknow, the socialist leader Jayaprakash Narayan, who had spent much of the year targeting the Government of India for its dictatorial tendencies and holding Nehru personally responsible for them, gave a long statement outlining his views:

It is a great tragedy that in a single-party Parliament the ruling party should take advantage of its majority to tamper even with Fundamental Rights. The very purpose of defining the Fundamental Rights in the Constitution is to place them beyond the interference of parliamentary majorities. Pandit Nehru’s repeated reference to the security of the State was itself a pointer to a grave danger that has been created for the future of Indian democracy. Except those in power, no one else in the country seems to be aware of any threat to the security of the State and yet these crippling amendments are sought to be made in the name of this danger.

Jayaprakash Narayan

Inside Parliament, however, an unruffled Prime Minister Nehru continued to rail against the press, its descent into ‘obscenity and vulgarity applied to politics’ and ‘the whole nature of the development of mechanical civilisation’ due to which the mind of the people was becoming mechanized. He was ashamed to see the cartoons that were printed in the newspapers, he denounced their degradation of public life, and fretted about the effects of such ‘freedom of speech’ on the morale of poor villagers and soldiers. He even raged about the low quality of human beings in India. He was thinking neither of the press nor of the upcoming election when he brought this amendment he piously affirmed, and repeatedly asked his colleagues to trust his words.

Given his own views as previously expressed both in his private correspondence and in his public statements, many of these pious affirmations were little short of outright lies. Neither Nehru nor his colleagues cared. Such moral edicts had already been consumed in the fiery birth of the postcolonial order.

On 31 May 1951, at 2 p.m., the Speaker called for a division on the motion for Parliament to take the bill into consideration. With 246 ayes to fourteen noes, the motion was passed. Twenty-nine members abstained. The announcement of the result was greeted with loud cheers. ‘Big Majority for Nehru Motion,’ read headlines the next morning. The final, decisive phase of the parliamentary battle had begun.

Reporting on the terminal debate on the amendment, one prominent newspaper wrote, ‘The Bill will be taken up for detailed consideration for the next two days and the guillotine will be applied at 1 p.m. on Saturday.’ It was a decidedly apt turn of phrase. For what was happening, as the liberal MP Hriday Nath Kunzru frequently and persistently proclaimed in Parliament, was nothing short of an amputation of some of the most vital fundamental rights provisions in the Constitution, the same ones that Prime Minister Nehru openly derided as ossified, archaic remnants of the ideas that fired the French and American Revolutions. The right to freedom of speech and the right to property were effectively being repealed.

On the evening of 31 May, Prof. K.K. Bhattacharya, Congress MP from Uttar Pradesh, wrote to Nehru seeking a free vote on the bill. ‘If you do not give me this freedom,’ he informed the prime minister, ‘it will be my painful duty to leave the Congress Party in Parliament so as to be free to vote in accordance with the dictates of my conscience.’ Nehru refused, and as Parliament convened on Friday, 1 June, Bhattacharya resigned from the Congress party and joined the ranks of the amendment’s opponents. Nonetheless, even with this late defection, Opposition leaders knew that there was little they could do: their loss was already preordained. Nothing they said, nothing they did could alter the unshakeable majority the Congress commanded. Still, they decided to fight to the last man. And the last two days witnessed fearsome verbal combat.

As each clause of the Constitution (First Amendment) Bill was taken up for discussion over 1 and 2 June, Opposition figures moved dozens of amendments to each clause. In the amendment to Article 15, H.V. Kamath attempted to add a proviso that special provisions for backward classes would not impose unreasonable restrictions upon the right to equality guaranteed to all citizens. Congress mutineer Shibban Lal Saksena pressed to include the word ‘economically’ in the description of ‘socially and educationally backward classes’. ‘If the amendment is allowed to pass in its present form,’ he averred, ‘it will mean that any class which has entrenched itself in power may use this clause to advance its own particular class’. Congress members such as M.A. Ayyangar from Madras remained unyielding in their claim that after the Scheduled Castes and Tribes, backward classes must be the first charge on the attention of the state.

Syama Prasad Mookerjee

When the amendments to Article 19 were taken up for discussion, Syama Prasad Mookerjee forcefully demanded that if the freedom of speech had to be curtailed, then the amendment should provide for such power to be vested solely in Parliament and not in the state legislatures to achieve uniformity across the country and minimize the chances of misuse. On this issue, Mookerjee traded lengthy, heated arguments with Home Minister C. Rajagopalachari and Law Minister B.R. Ambedkar. In impassioned, animated exchanges, both sides pointedly accused each other of obstinacy and irresponsibility. Prime Minister Nehru was charged with suppressing news from China that was critical of the communist regime, to which he replied that the news of communist atrocities in China and Tibet was grossly exaggerated.