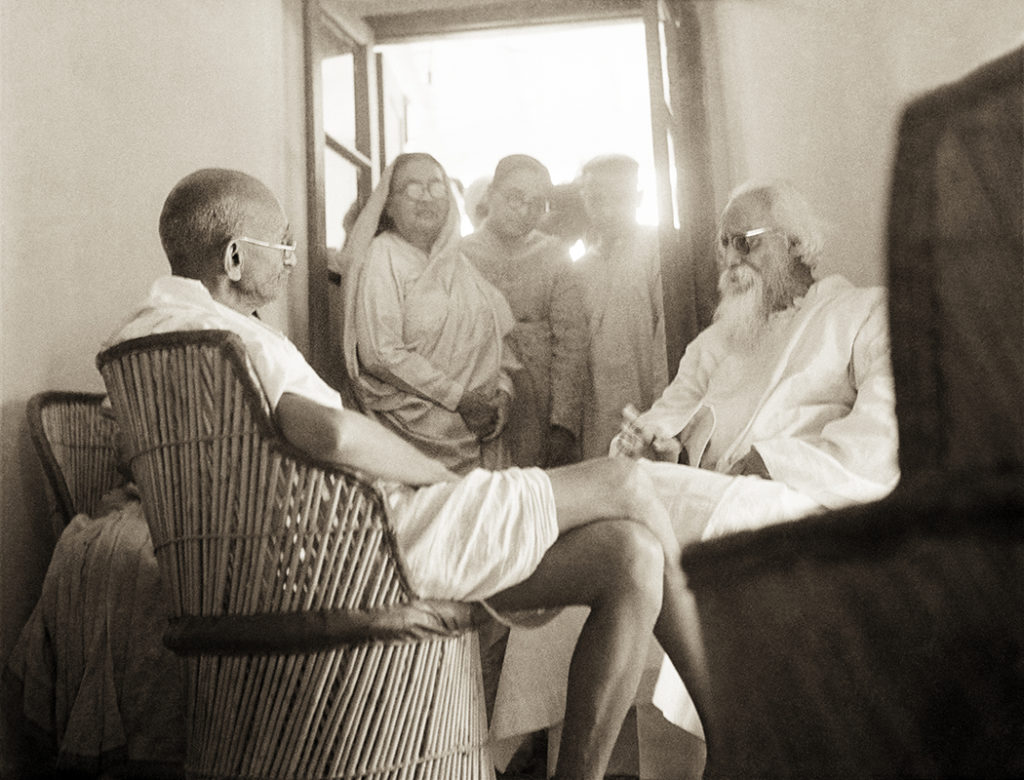

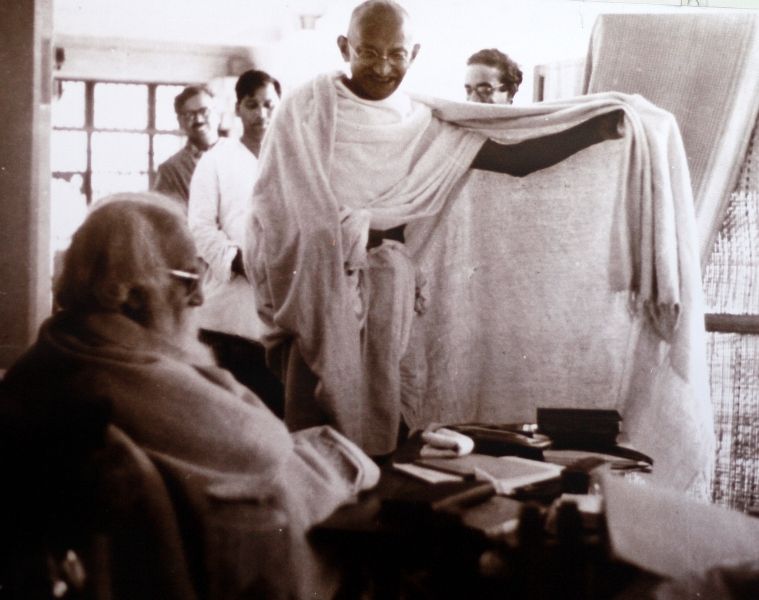

Mahatma Gandhi with Rabindranath Tagore, at Shantiniketan, February, 1940. Photograph by Kanu Gandhi/ © The Estate of Kanu Gandhi

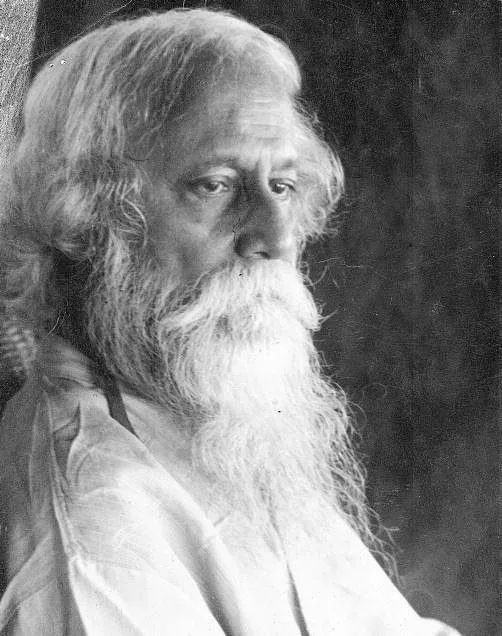

We recently carried a debate between Rabindranath Tagore and Mahatma Gandhi, where they argue for ‘Cooperation’ and ‘Non-Cooperation’, respectively, with a focus on the idea of ‘Soul-force’ (as opposed to ‘Brute-force’). This fascinating exchange between the two stalwarts contributed crucially to intellectual discourse—not just in the Indian subcontinent, but also abroad—at the height of the Non-Cooperation Movement in 1921.

Building upon his criticisms for Gandhi’s ideal of ‘Swaraj’ with the help of the ‘Charkha’, Tagore wrote another essay in 1925 titled ‘The Cult of the Charkha’ wherein he emphasized the demerits of relying merely on the spinning-wheel, in the hope of gaining independence. “Even if every one of our countrymen should betake himself to spinning thread,” Tagore writes. “That might somewhat mitigate their poverty, but it would not be Swaraj.” It is with this essay that we continue our series of ‘Great Debates’ that defined an epoch in Indian history and continues to be relevant today.

Tagore had always been apprehensive about the ‘machine-like’ existence of humans (you can read more about his concerns that the Western “civilization of humanity has lost its path in the wilderness of machinery” in his essay on nationalism that we have carried before). In this essay too, he maintains that when people follow a defined set of instructions as handed over to them by a “personality about whose moral earnestness they can have no doubt”, it hinders the capacity of their ‘mind’ to function on its own intellect. Mocking this ‘machine-mindedness’, he writes, “‘Mind!’ cry they, ‘What on earth is that? Why don’t you order us what to do and give some text for us to repeat from mouth to mouth and age to age?’” It is to a similar devolution of the mind, he suggests, that one may be able to attribute the system of caste, where individuals are boxed into a certain category based on their birth, without being allowed social mobility in terms of their occupational and intellectual skills: “This imitation of the social scheme of ant-life makes very easy the performance of petty routine duties, but specially difficult the attainment of manhood’s estate.”

It is in this context that Tagore begins his critique of Gandhi’s call for ‘charkha agitation’. To instill the importance of spinning thread in the minds of a population as diverse as that of India, he believes, is to choose to focus on simply one thread as a ‘short-cut’ to achieving self-rule. “Can it be expected,” asks Tagore. “That in the shrine of swaraj, the charkha goddess will attract to herself alone the offerings of every devotee?” Tagore further argues that in urging people to choose the charkha as a means to attain self-sufficiency, one ignores the various associated socio-economic aspects. Firstly, ‘cooperation’ is a necessary condition for actualizing the dream of gaining self-rule. Taking examples from Indian history itself, he argues that even in the days of invasions by Mughals or Pathans, when there was no scarcity of homespun thread, it could not succeed in binding diverse people together and vouch for stability. “If we have to get rid of this poverty which is visible outside, it can only be done by rousing our inward forces of wisdom of fellowship and mutual trust which make for cooperation.”

Secondly, spinning is a specialized occupation in itself that requires a particular set of skills. To ask each individual in the country to take to spinning is to belittle their other occupations and their respective intellectual strengths. “To ask the cultivator to spin, is to derail his mind. He may drag on with it for a while, but at the cost of disproportionate effort, and therefore waste of energy.” Thirdly, even if it is accepted that charkha is the principal means of gaining swaraj, according to Tagore, it only accounts for self-rule in the ‘external’ world: “…therein lies the reason why, when the defects of character and the perversions of social custom which obstruct its realisation are kept out of sight, and the whole attention is concentrated on home spun thread, no surprise is felt but rather relief.”

And finally, since nationalism for Tagore was never about a particular territory, he also emphasizes the progress of science in the West while opposing a complete reliance on the charkha. “When we forget that science is spreading the domain of Vishnu’s chakra, those who have honoured the Discus-Bearer to better purpose will spread their dominion over us. If we are wilfully blind to the grand vision of whirling forces, which science has revealed, the charkha will cease to have any message for us.”

Gandhi’s response to Tagore’s essays on the charkha and swaraj stands out for its extraordinary civility and for reflecting the mutual respect and friendship the two debaters shared. “If every disagreement were to displease,” writes Gandhi. “Since no two men agree exactly on all points, life would be a bundle of unpleasant sensations and therefore a perfect nuisance.” Gandhi begins by contrasting the role defined for him as a ‘Mahatma’ and for Tagore as a ‘poet.’ “The Poet lives in a magnificent world of his own creation—his world of ideas. I am a slave of somebody else’s creation—the spinning wheel.” And therefore, while there is no scope for competition between the two, it is important to bear in mind that the philosophical ideas of each complement the other. It is with this assertion that Gandhi respectfully denies the criticism of the poet: “The fact is that the Poet’s criticism is a poetic licence and he who takes it literally is in danger of finding himself in an awkward corner.”

He goes on to challenge the bard’s viewpoints by referring to them as picked up from “table talk.” To the critical argument of Tagore that one cannot expect everyone to spin at all times, Gandhi replies that “I have asked no one to abandon his calling, but on the contrary to adorn it by giving every day only thirty minutes to spinning as sacrifice for the whole nation.” To the accusatory remark by Tagore on the fact that spinning in a country as diverse as India requires a ‘union’ which appears to be lacking, Gandhi responds, “There is a sameness, identity or oneness behind the multiplicity and variety.” And to the question regarding whether one should choose the progress of science, as opposed to falling back on an old tradition, Gandhi argues that “Machinery has its place; it has come to stay. But it must not be allowed to displace the necessary human labour.” He goes on to highlight that socio-economic activities—such as the building up of a programme for an anti-malaria campaign, improved sanitation, settlement of village disputes, conservation and the breeding of cattle etc.—have begun due to the coming together of people to spin, by shedding their ‘idleness’, and having learned a lesson in ‘cooperation’. But this summary can hardly do justice to what is the debate of a century. We urge you to read the entire exchange between these two giants, published below, to better understand the positions and philosophies of each.

(Tagore’s contribution to the controversy on “The Cult of the Charkha”, which appeared in Modern Review on September 1925)

Acharya Prafulla Chandra Ray has marked me with his censure in printer’s ink, for that I have been unable to display enthusiasm in the turning of the charkha. But, because it is impossible for him to be pitiless to me even when awarding punishment, he has provided me with a companion in my ignominy in the illustrious person of Acharya Brajendra Nath Seal. That has taken away the pain of it and also given me fresh proof of the eternal human truth that we are in agreement with some people and with some others we are not. It only proves that while creating man’s mind, God did not have for his model the spider mentality doomed to a perpetual conformity in its production of web and that it is an outrage upon human nature to force it through a mill and reduce it to some stardardised commodity of uniform size and shape and purpose.

When in my younger days I used to go boating on the river, the boatmen of Jagannath Ghat would swarm around, each pressing on me the service of his own particular vessel. My selection once made, however, there would be no further trouble; for, if the boats were many so were the passengers, and the places to go to were likewise various. But suppose one of the boats had been specially hall-marked, as the one and only sacred ferry by some dream emanating from the shrine of Tarakeswar, then indeed it would have been difficult to withstand the extortions of its touts, despite the inner conviction of the travellers that though the shore opposite may be one, its landing places are many and diversely situated.

Our shastras tell us that the divine shakti is many-sided so that a host of different factors operate in the work of creation. In death these merge into sameness; for chaos alone is uniform. God has given to man the same many-sided shakti for which reason the civilisation of his creation have their divine wealth of diversity. It is God’s purpose that in the societies of man the various should be strung together into a garland of unity; while often the mortal providence of our public life, greedy for particular results, seeks to knead them all into a lump of uniformity. That is why we seeing the concerns of this world so many identically liveried, machine-made workers, so many marionettes pulled by the same string, and on the other hand, where the human spirit has not been reduced to the coldness of collapse, we also see perpetual rebelliousness against this mechanical mortar pounded homogeneity.

If in any country we find no symptom of such rebellion, if we find its people submissively or contentedly prone on the dust, in dumb terror of some master’s bludgeon, or blind acceptance of some guru’s injunction, then indeed should we know that for such a country, in extremis, it is high time to mourn.

If in any country we find no symptom of such rebellion, if we find its people submissively or contentedly prone on the dust, in dumb terror of some master’s bludgeon, or blind acceptance of some guru’s injunction, then indeed should we know that for such a country, in extremis, it is high time to mourn.

In our country, this ominous process of being levelled down into sameness has long been at work. Every individual of every caste has his function assigned to him, together with the obsession into which he has been hypnotised, that, since he is bound by some divine mandate, accepted by his first ancestor, it would be sinful for him to seek relief therefrom. This imitation of the social scheme of ant-life makes very easy the performance of petty routine duties, but specially difficult the attainment of manhood’s estate. It imparts skill to the limbs of the man who is a bondsman, whose labour is drudgery; but it kills the mind of a man who is a doer, whose work is creation. So in India, during long ages past, we have the spectacle of only a repetition of that which has gone before.

In the process of this continuous grind India has acquired a distaste for very existence. In dread of the perpetuation of this same grind, through the eternal repetition of births, she is ready to intern all mental faculties in absolute inaction in order to cut at the root of Karma itself. For only too well has she realised, in the dreary round of her daily habit the terribleness of this everlasting recapitulation. Moreover, this dreariness is not the only loss sustained by those who have suffered themselves to be reduced to a machinelike existence; for they have also lost all power to combat aggression or exploitation. From age to age, they have been assaulted by the strong, defrauded by the cunning and deluded by the gurus to whom their conscience was surrendered. Such a state of abject passivity has become easy because of the teaching that through an immutable decree of providence, they have been set adrift on the sea of Time, upon the raft of monotonous living death, burdened with a vocation that makes no allowance for variation in human nature.

But whatever our shastras may or may not have said, this popular conception of the Creator’s doing is the very opposite of what he really did do to man at the moment of his creation. Instead of furnishing him with an automatically revolving grind-stone—God slipped into his constitution that most lively sprightly thing called Mind. And unless man can be made to get rid of this mind it will remain impossible to convert him into a machine. In so far as the men at the top succeeded in paralysing the people’s minds by fear—or greed or hypnotic texts, they succeeded in extorting—from one class of them, only textiles from their looms; from another class, only pots from their wheels; from a third, only oil from their mills. Now when from such persons as these it becomes necessary to demand the application of their mind to any big work on hand, they stand aghast, “Mind!” cry they, “What on earth is that? Why don’t you order us what to do and give some text for us to repeat from mouth to mouth and age to age?”

Our mind, in doing duty only as a hedge to prevent the encroachment of living ideas, had been kept evenly clipped short for the purpose. If, in spite of that, in this age of self-assertion, we find mischievous branches trying to make room for the disturbance of the spruceness of the trimming,—if all over minds refuse incessantly to reverberate some one set mantram, in the droning chirp of the cicadas of the night,—let no one be annoyed or alarmed; for only because of this does the attainment of Swaraj become thinkable!

That is why I am not ashamed,—though there is every reason to be afraid,—to admit that the depths of my mind have not been moved by the charkha agitation. This may be counted by many as sheer presumption on my part, they may even wax abusive; for swearing is a much needed relief for the feelings when even one stray fish happens to elude the all-embracing net. Still, I cannot help doing that there are others who are in the same plight as myself,—though it is difficult to find them all out. For even where hands are reluctant to work the spindle, mouths are all the more busy spinning its praises.

I am strongly of opinion that all intense pressure of persuasion brought upon the crowd psychology is unhealthy for it. Some strong and wide-spread intoxication of belief among a vast number of men can suddenly produce a convenient uniformity of purpose, immense and powerful. It seems for the moment a miracle of a wholesale conversion; and a catastrophic phenomenon of this nature stuns our rational mind, raising high some hope of easy realisation which is very much like a boom in the business market. The amazingly immediate success is no Criterion of its reality,—the very dimension of its triumph having a dangerous effect of producing a sudden and universal eclipse of our judgment. Human nature has its elasticity; and in the name of urgency, it can be forced towards a particular direction far beyond its normal and wholesome limits. But the rebound is sure to follow, and the consequent disillusionment will leave behind it a desert track of demoralisation. We have had our experience of this in the tremendous exultation lately produced by the imaginary easy prospect of Hindu-Muslim unity. And therefore I am afraid of a blind faith on a very large scale in the charkha, in the country, which is so liable to succumb to the lure of short cuts when pointed out by a personality about whose moral earnestness they can have no doubt.

I am afraid of a blind faith on a very large scale in the charkha, in the country, which is so liable to succumb to the lure of short cuts when pointed out by a personality about whose moral earnestness they can have no doubt.

Anyhow what I say is this. If, today, poverty has come upon our country, we should know that the root cause is complexly ramified and it dwells within ourselves. For the whole country to fall upon only one of its external symptoms with the application of one and the same remedy will not serve to fight the demon away. If man had been a mindless image of stone, a defect in his features might have been cured with hammer and chisel; but when his shrunken features bespeak vital poverty, the cure must be constitutional, not formal; and repeated hammer strokes upon some one particular external point will only damage that same life still more.

In the days when our country had to bear the brunt of Mughal and Pathan—the little jerry-built edifices of Hindu sovereignty fell to pieces on every side. There was then no dearth of home-spun thread, but that did not serve to bind these into stability. And, yet, in those days there was no economic antagonism between the people and their rulers. The throne of the latter was established on the soil of the country, so that the ripe fruits fell to the ground where the trees stood. Can it then be today— when we have not one or two kings—but a veritable flood of them sweeping away our life-stuffs across the seas away from our motherland, causing it to lose both its fruits and its fertility,—can it be, I say, that the lack of sufficient thread prevents our stemming this current? Is it not rather our lack of vitality, our lack of union?

In the days when our country had to bear the brunt of Mughal and Pathan—the little jerry-built edifices of Hindu sovereignty fell to pieces on every side. There was then no dearth of home-spun thread, but that did not serve to bind these into stability. And, yet, in those days there was no economic antagonism between the people and their rulers… Can it then be today— when we have not one or two kings—but a veritable flood of them sweeping away our life-stuffs across the seas away from our motherland, causing it to lose both its fruits and its fertility,—can it be, I say, that the lack of sufficient thread prevents our stemming this current? Is it not rather our lack of vitality, our lack of union?

Some will urge that though in the days of Mughal and Pathan we had not sovereign power, we had at least a sufficiency of food and clothing. When the river is not flowing, it may be possible to bank up little pools in its bed to hold water enough for our needs, conveniently at hand for each. But can such banks guarding our scanty economic resources for local use withstand the shocks which come upon it today from far and near? No longer will it be possible to hide ourselves away from commerce with the outside world. Moreover such isolation itself would be the greatest of deprivations for us. If, therefore, we cannot rouse the forces of our mind, in adequate strength to take our due part in this traffic of exchanging commodities, our grain will continue to be consumed by others, leaving only the chaff as our own portion. In Bengal we have a nursery rhyme which soothes the infant with the assurance that it will get the lollipop if only it twirls its hands. But is it a likely policy to reassure grown up people by telling them that they will get their swaraj, that is to say, get rid of all poverty, in spite of their social habits that are a perpetual impediment and mental habits producing inertia of intellect and will,—by simply twirling away with their hands? No. If we have to get rid of this poverty which is visible outside, it can only be done by rousing our inward forces of wisdom of fellowship and mutual trust which make for cooperation.

But, it may be argued, does not external work react on the mind? It does, only if it has its constant suggestions to our intellect, which is the master, and not merely its commands for our muscles, which are slaves. In this clerk ridden country, for instance, we all know that the routine of clerkship is not mentally stimulating. By doing the same thing day after day mechanical skill may be acquired; but the mind like a mill-turning bullock will be kept going round and round a narrow range of habit. That is why, in every country man has looked down on work which involves this kind of mechanical repetition. Carlyle may have proclaimed the dignity of labour in his stentorian accents, but a still louder cry has gone up from humanity, age after age, testifying to its indignity. “The wise man sacrifices the half to avert a total loss”—so says our Sanskrit proverb. Rather than die of starvation, one can understand a man preferring to allow his mind to be killed. But it would be a cruel joke to try to console him by talking of the dignity of such sacrifice.

In fact, humanity has ever been beset with the grave problem, how to rescue the large majority of the people from being reduced to the stage of machines. It is my belief that all the civilisations, which have ceased to be, have come by their death when the mind of the majority got killed under some pressure by the minority; for the truest wealth of man is his mind. No amount of respect outwardly accorded, can save man from the inherent ingloriousness of labour divorced from mind. Only those who feel that they have become inwardly small can be belittled by others, and the numbers of the higher castes have ever dominated over those of the lower, not because they have any accidental advantage of power, but because the latter are themselves humbly conscious of their dwarfed humanity. If the cultivation of science by Europe has any moral significance, it is in its rescue of man from outrage by nature, not its use of man as a machine but its use of the machine to harness the forces of nature in man’s service. One thing is certain, that the all-embracing poverty which has overwhelmed our country cannot be removed by working with our hands to the neglect of science. Nothing can be more undignified drudgery than that man’s knowing should stop dead and his doing go on for ever.

It was a great day for man when he discovered the wheel. The facility of motion thus given to inert matter enabled it to bear much of man’s burden. This was but right, for Matter is the true shudra; while with his dual existence in body and mind, Man is a dwija. Man has to maintain both his inner and outer life. Whatever functions he cannot perform by material means are left as an additional burden on himself, bringing him to this extent down to the level of matter, and making him a shudra. Such shudras cannot obtain glory by being merely glorified in words.

Matter is the true shudra; while with his dual existence in body and mind, Man is a dwija. Man has to maintain both his inner and outer life. Whatever functions he cannot perform by material means are left as an additional burden on himself, bringing him to this extent down to the level of matter, and making him a shudra. Such shudras cannot obtain glory by being merely glorified in words.

Thus, whether in the shape of the spinning wheel, or the potter’s wheel or the wheel of a vehicle, the wheel has rescued innumerable men from the shudra’s estate and lightened their burdens. No wealth is greater than this lightening of man’s material burdens. This fact man has realised ever more and more, since the time when he turned his first wheel; for his wealth has thereupon gone on compounding itself in ever-increasing rotation, refusing to be confined to the limited advantage of the original charkha.

Is there no permanent truth underlying these facts? One aspect of Vishnu’s shakti is the Padma, the beautiful lotus; another is the Chakra, the movable discus. The one is the complete ideal of perfection, the other is the process of movement, the ever active power seeking fulfillment. When man attained touch with this moving shakti of Vishnu, he was liberated from that inertia which is the origin of all poverty. All divine power is infinite. Man has not yet come to the end of the power of the revolving wheel. So, if we are taught that in the pristine charkha we have exhausted all the means of spinning thread, we shall not gain the full favour of Vishnu. Neither will his spouse Lakshmi smile on us. When we forget that science is spreading the domain of Vishnu’s chakra, those who have honoured the Discus-Bearer to better purpose will spread their dominion over us. If we are wilfully blind to the grand vision of whirling forces, which science has revealed, the charkha will cease to have any message for us. The hum of the spinning wheel, which once carried us so long a distance on the path of wealth, will no longer talk to us of progress.

Some have protested that they never preached that only the turning of the charkha should be engaged in. But they have not spoken of any other necessary work. Only one means of attaining swaraj has been definitely ordered and the rest is a vast silence. Does not such silence amount to a speech stronger than any uttered word? Is not the charkha thrust out against the background of this silence into undue prominence? Is it really so big as all that? Has it really the divinity which may enable it to appropriate the single-minded devotion of all the millions of India, despite their diversity of temperament and talent? Repeated efforts, even unto violence and bloodshed, have been made, all the world over, to bring mankind together on the basis of the common worship of a common Deity, but even these have not been successful. Neither has a common God been found, nor a common form of worship. Can it then be expected that, in the shrine of swaraj, the charkha goddess will attract to herself alone the offerings of every devotee? Surely such expectation amounts to a distrust of human nature, a disrespect for India’s people.

Can it then be expected that, in the shrine of swaraj, the charkha goddess will attract to herself alone the offerings of every devotee? Surely such expectation amounts to a distrust of human nature, a disrespect for India’s people.

In my childhood, I had an up-country servant, called Gopee, who used to tell us how once he went to Puri on a pilgrimage, and was at a loss what fruit to offer to Jagannath, since any fruit so offered could not be eaten by him anymore. After repeatedly going over the list of edible fruits known to him he suddenly bethought himself of the tomato (which had very little fascination for him) and the tomato it was which he offered, never having reason to repent of such clever abnegation. But to call upon man to make the easiest of offerings to the smallest of gods is the greatest of insults to his manhood. To ask all the millions of our people to spin the charkha is as bad as offering the tomato to Jagannath. I do hope and trust that there are not thirty-three crores of Gopees in India. When man receives the call of the great to make some sacrifice, he is indeed exalted; for then he comes to himself with a start of revelation,—to find that he too has been bearing his hidden resources of greatness.

Our country is the land of rites and ceremonials, so that we have more faith in worshipping the feet of the priest than the Divinity whom he serves. We cannot get rid of the conviction that we can safely cheat our inner self of its claims, if we can but bribe some outside agency. This reliance on outward help is a symptom of slavishness, for no habit can more easily destroy all reliance on self. Only to such a country can come the charkha as the emblem of her deliverance and the people dazed into obedience by some spacious temptation go on turning their charkha in the seclusion of their corners, dreaming all the while that the car of Swaraj of itself rolls onward in triumphal progress at every turn of their wheel.

And so it becomes necessary to restate afresh the old truth that the foundation of Swaraj cannot be based on any external conformity, but only on the internal union of hearts. If a great union is to be achieved, its field must be great likewise. But if out of the whole field of economic endeavour only one fractional portion be selected for special concentration thereon, then we may get home-spun thread, and even genuine khaddar, but we shall not have united, in the pursuit of one great complete purpose, the lives of our countrymen.

In India, it is not possible for everyone to unite in the realm of religion. The attempt to unite on the political platform is of recent growth and will yet take long to permeate the masses. So that the religion of economics is where we should above all try to bring about this union of ours. It is certainly the largest field available to us; for here high and low, learned and ignorant, and ail have their scope. If this field ceases to be one of warfare, if there we can prove, that not competition but cooperation is the real truth, then indeed we can reclaim from the hands of the Evil One an immense territory for the reign of peace and goodwill. It is important to remember, moreover, that this is the ground where on our village communities had actually practised unity in the past. What if the thread of the old union has snapped? It may again be joined together, for such former practice has left in our character the potentiality of its renewal.

In India, it is not possible for everyone to unite in the realm of religion. The attempt to unite on the political platform is of recent growth and will yet take long to permeate the masses. So that the religion of economics is where we should above all try to bring about this union of ours. It is certainly the largest field available to us; for here high and low, learned and ignorant, and ail have their scope. If this field ceases to be one of warfare, if there we can prove, that not competition but cooperation is the real truth, then indeed we can reclaim from the hands of the Evil One an immense territory for the reign of peace and goodwill.

As is livelihood for the individual, so is politics for a particular people,—a field for the exercise of their business instincts of patriotism. All this time, just as business has implied antagonism so has politics been concerned with the self-interest of a pugnacious nationalism. The forging of arms and of false documents has been its main activity. The burden of competitive armaments has been increasing apace, with no end to it in sight, no peace for the world in prospect.

When it becomes clear to man that in the co-operation of nations lies the true interest of each,—for man is established in mutuality—then only can politics become a field for true endeavour. Then will the same means which the individual recognises as moral and therefore true, be also recognised as such by the nations. They will know that cheating, robbery and the exclusive pursuit of self-aggrandisement are as harmful for the purposes of this world as they are deemed to be for those of the next. It may be that the League of Nations will prove to be the first step in the

process of this realisation.

Again, just as fee present day politics is a manifestation of extreme individualism in nations, so is fee process of gaining a livelihood an expression of fee extreme selfishness of individuals. That is why man has descended to such depths of deceit and cruelty in his indiscriminate competition. And yet, since man is man, even in his business he ought to have cultivated his humanity rather than fee powers of exploitation. In working for his livelihood he ought to have earned not only his daily bread but also his eternal truth.

When, years ago, I first became acquainted with the principles of cooperation in the field of business, one of the knots of a tangled problem, which had long perplexed my mind seemed to have been unravelled, I felt that the separateness of self-interest, which had so long contemptuously ignored the claims of the truth of man was at length to be replaced by a combination of common interests which would help to uphold that truth, proclaiming that poverty lay in the separation, and wealth in the union of man and man. For myself I had never believed that this original truth of man could find its limit in any region of his activity.

The cooperative principle tells us, in the field of man’s livelihood, that only when he arrives at his truth can he get rid of his poverty,—not by any external means. And the manhood of man is at length honoured by the enunciation of this principle. Cooperation is an ideal, not a mere system, and therefore it can give rise to innumerable methods of its application. It leads us into no blind alley; for at every step it communes with our spirit. And so, it seemed to me, in its wake would come, not merely food, but the goddess of plenty herself, in whom all kinds of material food are established in an essential moral oneness.

It was while some of us were thinking of the ways and means of adopting this principle in our institution that I came across the book called The National Being written by that Irish idealist, A. E. who has a rare combination in himself of poetry and practical wisdom. There I could see a great concrete realisation of the co-operative living of my dreams. It became vividly clear to me what varied results could flow therefrom, how full the life of man could be made thereby. I could understand how great the concrete truth was in any plane of life, the truth that in separation is bondage, in union is liberation. It has been said in the Upanishad that Brahma is reason, Brahma is spirit but Anna also is Brahma, which means that food also represents an internal truth, and therefore through it we may arrive at a great realisation, if we travel along the true path.

I know there will be many to tax me with indicating a solution of great difficulty. To give concrete shape to the ideal of cooperation on so vast a scale will involve endless toil in experiment and failure, before at length it may become an accomplished fact. No doubt it is difficult. Nothing great can be got cheap. We only cheat ourselves When we try to acquire things that are precious with a price that is inadequate. The problem of our poverty being complex, with its origin in our ignorance and unwisdom, in the inaptitude of our habits, the weakness of our character, it can only be effectively attacked by taking in hand our life as a whole and finding both internal and external remedies for the malady which afflicts it. How can there be an easy solution?

There are many who assert and some who believe that swaraj can be attained by the charkha; but I have yet to meet a person who has a clear idea of the process. That is why there is no discussion, but only quarreling over the question. If I state that it is not possible to repel foreign invaders armed with guns and cannons by the indigenous bow and arrow, there will I suppose be still some to contradict me asking, ‘Why not?’ It has already been said by some, “Would not the foreigners be drowned even if every one of our three hundred and thirty millions were only to spit at them?” While not denying the fearsomeness of such a flood, or the efficacy of such a suggestion, for throwing odium on foreign military science, the difficulty which my mind feels to be insuperable is that you can never get all these millions even to spit in unison. It is too simple for human beings. The same difficulty applies to the charkha solution.

The disappointments, the failures, the recommencements that Sir Horace Plunkett had to face when he set to work to apply the cooperative principle in the economic reconstruction of Ireland, are a matter of history. But though it takes time to start a fire, once alight it spreads rapidly. That is the way with truth as well. In whatever corner of the earth it may take root, the range of its seeds is worldwide, and everywhere they may find soil for growth and give of their fruit to each locality. Sir Horace Plunkett’s success was not confined to Ireland alone; he achieved also the possibility of success for India. If any true devotee of our motherland should be able to eradicate the poverty of only one of her villages, he will have given permanent wealth to the thirty three crores of his countrymen. Those who are wont to measure truth by its size get only an outside view and fail to realise that each seed, in its tiny vital spark, brings divine authority to conquer the whole world.

As I am writing this, a friend objects that even though I may be right in thinking that the charkha is not competent to bring us swaraj, or remove the whole of our poverty, why ignore such virtues as it admittedly possesses? Every farmer, every householder, has a great deal of leisure left over after his ordinary work is done; so that if everyone would utilise such spare time in productive work much could be done towards the alleviation of our poverty. Why not glorify the charkha as one of the instruments of such a desirable consummation? This reminds me of a similar proposition I have heard before. Most of our people throw away the water in which their rice is boiled. If everyone conserved this nutritious fluid that would go a long way to solve the food problem. I admit there is truth in this contention. The slight change of taste required for eating boiled rice with its water retained should not be very difficult to acquire, in view of the object sought to be gained. Many other similar savings could be effected which are doubtless worth the effort and should be looked upon as a duty. But has any one ever suggested that the conservation of rice-water should be made a plank in the platform of swaraj work? And is there no good reason for the omission?

In order to make my point clear, let me take an instance from the case of religion. If a preacher should repeatedly and insistently urge that the drinking of water from any and every well is the cause of the degeneracy of our religion, then the chief objection to his teaching would be its tendency to debase the value of moral action as a factor in religion. No doubt there is the chance of some well or other containing impure water; impure water destroys health; a diseased body begets a diseased mind; and therefore spiritual welfare is in danger. I am not concerned to dispute the truth in all this, yet I must repeat that to give undue value to the comparatively unimportant, lowers the value of the important. And so we find that there are numbers of Hindus who would not hesitate even to kill a Mohamedan if he came to draw water from their own well. If the small be put on an equal footing with the big, it is not content to rest there, but needs must push its way higher up. That is how the injunction: “Thou shalt not drink dubious water” gets the better of the commandment, “Thou shalt not kill”. There is no end to the perversions of value which have become habituated to their facile intrusion that no one is surprised to see the charkha stalk the land, with uplifted club, in the garb of swaraj itself. The charkha is doing harm because of the undue prominence, which it has thus usurped where by it only adds fuel to the smouldering weakness that is eating into our vitals. Suppose some mighty voice should next proclaim that the rice water must not be suffered to enter our councils. Given requisite forcefulness that may lead to the flow of rice water being followed by the flow of human blood, in the sacred name of political purity. If the idea of the impurity of foreign textiles should effect a lodgement in our mind along with the numerous fixed ideas already there, in regard to the impurity of certain food and waters, the Id riots, to which we are accustomed, might pale before the sanguinary strife that may eventually be set ablaze between the so-called unclean lot who may use foreign cloth and those politically pure souls who do not. The danger to my mind is that the contagion of “untouchability”, which was hitherto confined to our society, may extend to the economic and political spheres as well.

If the idea of the impurity of foreign textiles should effect a lodgement in our mind along with the numerous fixed ideas already there, in regard to the impurity of certain food and waters, the Id riots, to which we are accustomed, might pale before the sanguinary strife that may eventually be set ablaze between the so-called unclean lot who may use foreign cloth and those politically pure souls who do not. The danger to my mind is that the contagion of “untouchability”, which was hitherto confined to our society, may extend to the economic and political spheres as well.

Some one whispers to me feat to combine in charkha spinning is cooperation itself. I beg to disagree. If all fee higher caste people of fee Hindu community combine in keeping their well water undefiled from use of fee lower ones this practice in itself does not give it fee dignity of Bacteriology. It is a particular action isolated from fee comprehensive vision of this science. And therefore while we keep our wells reserved for fee cleaner sect, we allow our ponds to get polluted, fee ditches round our houses to harbour messengers of death. Those who intimately know Bengal also know that at fee time of preparing a special kind of pickle our women take extra precaution in keeping themselves clean. In fact they go through a kind of ceremonial of ablution and other forms of purifications. For such extra care their pickle survives fee ravage of time, while their villages are devastated by epidemics. For while there may remain some Pasteur’s law invisible at fee depth of this pickle-making precaution, fee diseased spleens in fee neighbourhood make themselves only too evident by their magnitude. The universal application of Pasteur’s law in fee production of pickle has some similarity to fee application of fee principle of a cooperation method of livelihood in turning fee spinning wheel. It may produce enormous quantity of yarn, but fee blind suppression of intellect which guards our poverty in its dark dungeon will remain inviolate. This narrow activity will shed light only upon one detached piece of fact keeping its great background of truth densely dark.

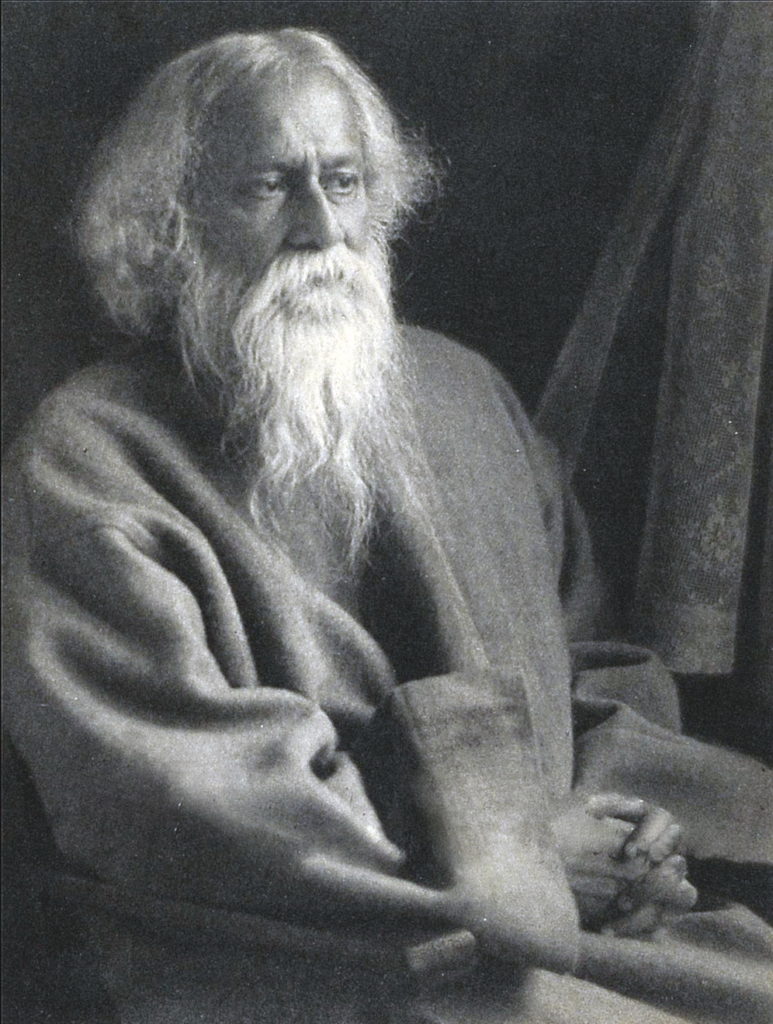

It is extremely distasteful to me to have to differ from Mahatma Gandhi in regard to any matter of principle or method. Not that, from a higher standpoint, there is anything wrong in so doing; but my heart shrinks from it. For what could be a greater joy than to join hands in the field of work with one for whom one has such love and reverence? Nothing is more wonderful to me than Mahatmaji’s great moral personality. In him divine providence has given us a burning thunderbolt of shakti. May this shakti give power to India,—not overwhelm her,—that is my prayer! The difference in our standpoints and temperaments has made the Mahatma look upon Rammohun Roy as a pygmy—while I revere him as a giant. The same difference makes the Mahatma’s field of work one which my conscience cannot accept as its own. That is a regret which will abide with me always. It is, however, God’s will that man’s paths of endeavour shall be various, else why these differences of mentality. How often have any personal feelings of regard strongly urged me to accept at Mahatma Gandhi’s hands my enlistment as a follower of the charkha cult, but as often have my reason and conscience restrained me, lest I should be a party to the raising of the charkha to a higher place than is its due, thereby distracting attention from other more important factors in our task of all-round reconstruction. I feel sure that Mahatma himself will not foil to understand me, and keep for me the same forbearance which he has always had. Acharya Roy, I also believe, has respect for independence of opinion, even when unpopular; so that, although when carried away by the fervour of his own propaganda he may now and then give me a scolding, I doubt not he retains for me a soft corner in his heart. As for my countrymen the public,—accustomed as they are to drown, under the facile flow of their minds, both past services and past disservices done to them,—if today they cannot find it in their hearts to forgive, they will forget tomorrow. Even if they do not,—if for me their displeasure is fated to be permanent, then just as today I have Acharya Seal as my fellow culprit, so tomorrow I may find at my side persons rejected by their own country whose reliance reveals the black unreality of any stigma of popular disapprobation.

(In the September 1925 issue of Modern Review, Tagore raised some more questions about Charkha and Swaraj)

Our wise men have warned us, in solemn accents of Sanskrit, to talk away as much as we like, but never to write it down. There are proofs, many of them, that I have habitually disregarded this sage advice, following it only when called upon to reply. I have never hesitated to write, whenever I had anything to say, be it in prose or in verse, controversy alone excepted,—for on that my pen has long ceased to function.

Such of our beliefs as become obsessions are hardly ever made up of pure reason,— our temperament, or moods of the moment, mainly go to their fashioning. It is but rarely that we believe, because we have found a good reason. We most often seek reasons because we believe. Only in Science do our conclusions follow upon strict proofs; while the rest of them, under the influence of our attractions and repulsions, keep circling round the centre of our personal predilections. This is all the more true when our belief is the outcome of a desire for some particular result specially when that desire is shared by a large number of our fellow men. In such case no reason needs to be adduced in order to persuade people into a common course, it being sufficient if such course is fairly easy, and, above all, if the hope is roused of speedy success.

It is some time since the minds of our countrymen have been kept in a state of agitation by the idea that swaraj may be easily and speedily attained, in this unsettled atmosphere of popular excitement any attempt at a discussion of pros and cons does but bring down a cyclonic storm, in which it becomes almost hopeless to expect the vessel of reason to make sail for any part of destination. Hitherto, we had always thought that the achievement of swaraj was a difficult matter. So, when it came to our ears that, on the contrary, it was extremely easy, and by no means impossible to reach in a very short time, who could have the heart to raise questions or obtrude arguments? Those who were enthusiastic over the prospect of faqir turning a copper coin into a gold mohur, are able to do so, not because they are lacking in intellect, but because their avidity restrains them from exercising their intelligence.

Anyhow, it was only the other day that our people were beside themselves at the message that Swaraj was at our very door. Then when the appointed time for its advent had slipped by, it was given out that the disappointment was due to our non-fulfillment of the conditions. But few thereupon paused to consider that it was just in the fulfillment of these conditions that the difficulty lay. Is it not a self-evident truth that we do not have Swaraj simply because we do not fulfil its conditions? It goes without saying that if Hindu and Moslem should come together in amity and good fellowship, that would be a great step towards its realisation. But the trouble always is, the Hindu and Moslem do not come together. Had their union been real, all the 365 days in the calendar would have been auspicious days for making the venture. True, the announcement of a definite date for the start has an intoxicating effect. But I cannot admit that an intoxicating state makes the journey any easier.

The appointed time has not long gone by, yet the intoxication lingers,—the intoxication which consists in a confusion of haste with speed, in a befogged reliance on one or two narrow paths as the sole means of gaining a vast realisation. Amongst those paths prominently looms the charkha.

And so the question has to be raised: What is this swaraj? Our political leaders have refrained from giving us any dear explanation of it. As a matter of feet we have the freedom to spin our own thread on our own charkha. If we have omitted to avail ourselves of it, that is because the thread so spun cannot compete with the product of the power mill. No doubt it might have been otherwise if the millions of India had devoted their leisure to the charkha, thereby reducing the exchange value of home spun thread. But nothing proves the hopelessness of such an expectation more than the fact that those very persons who are wielding their pens in its support are not wielding the charkha itself.

The second point is, even if every one of our countrymen should betake himself to spinning thread, that might somewhat mitigate their poverty, but it would not be Swaraj. What of that? Is the increase of wealth a small thing for a poverty stricken country? What a difference it would make if our cultivators, who improvidently waste their spare time, were to engage in such productive work! Let us concede for the moment that the profitable employment of the surplus time of the cultivator is of the first importance. But the thing is not so simple as it sounds. One who takes up the problem must be prepared to devote precise thinking and systematic endeavour to its solution. It is not enough to say: Let them spin.

…even if every one of our countrymen should betake himself to spinning thread, that might somewhat mitigate their poverty, but it would not be Swaraj. What of that? Is the increase of wealth a small thing for a poverty stricken country? What a difference it would make if our cultivators, who improvidently waste their spare time, were to engage in such productive work! Let us concede for the moment that the profitable employment of the surplus time of the cultivator is of the first importance. But the thing is not so simple as it sounds. One who takes up the problem must be prepared to devote precise thinking and systematic endeavour to its solution. It is not enough to say: Let them spin.

The cultivator has acquired a special skill with his hands, and a special bent of mind, by dint of consistent application to his own particular work. The work of cultivation is for him the line of least strain. So long as he is working, he is busy with one or other of the operations connected therewith: when he is not so busy, he is not at work. It would be unfair to charge him with laziness on this account. Had the processes of cultivation lasted throughout the year, he also would have been at work from one end of it to the other. It is an inherent defect of all routine toil, such as is the work of cultivation, that it dulls the mind by disuse. In order to be able to go from one habitual round of daily work to a different one, an active mind is required. But this kind of manual labour, like a tram car, runs along a fixed track, and cannot take a different course with any ease, however dire the necessity. To ask the cultivator to spin, is to derail his mind. He may drag on with it for a while, but at the cost of disproportionate effort, and therefore waste of energy.

I have an intimate acquaintance with the cultivators of at least two districts of our province and I know from experience how rigorous for them are the bonds of habit. One of these districts is mainly rice-producing and there the cultivators have to toil with might and main to grow their single crop of rice. Nevertheless in their spare time, they might have realised growing green vegetables round their homesteads. I tried to encourage them to do so, but failed. The very men who willingly sweated over their rice, refused to stir for the sake of vegetables. In the other district the cultivators are busy, all the year round with rice, jute and sugarcane, mustard and other spring crops. Such portions of their holdings as do not bear any of these, are left fallow, without any corresponding remissions of rent. To this same locality come peasants from the North-West, who take up, and pay a good rent for similar waste

lands and, raising thereon different varieties of melon, return home with a substantial profit. The producer of jute can by no means be called lazy. I am told there are other places in the world quite as suitable for growing jute, where the fanners nevertheless refuse to undergo the hardships of its cultivation. It would seem, therefore, that if Bengal has a monopoly of jute, that is more due to the character of her peasants than of her soil. And yet these hard-working jute cultivators, with the example before their very eyes of the profits made by those up-country melon growers, do not care to follow it in the case of their own fallow holdings by treading a path to which they are unaccustomed.

Therefore, when we are faced with any such problem, the difficulty we have to contend with is how to draw the mind of the people out of its path of habit into a new one. I cannot believe that it is enough to indicate some easy external method; the solution, as I say, is a question of change of mentality.

It is not difficult to issue from outside the mandates: Let Hindu and Moslem unite. At this the obedient Hindus may flock to join the Khilafat movement, for such conjunction is easy enough. They may even yield some of their worldly advantages in favour of the Moslems, for though that be more difficult, it is still of the outside. But the real difficulty is for Hindus and Moslems to give up their respective prejudices which keep them apart. That is where the problem now rests. To the Hindu, the Mussalman is impure: for the Mussalman, the Hindu is a kafir. In spite of their longing for swaraj neither can forget this inward obsession. I used to know an anglicised Hindu who had leanings towards European fare. Everything else he would heartily relish, but he drew the line at hotel cooked rice, rice touched by Mussalman cooks, said he, refused to pass his lips. The same kind of prejudice which makes such rice taboo, stands in the way of cordial relationship. The habit of mind which religious injunctions have ingrained in us constitutes the age old fortress which holds our anti-Moslem feeling secure against penetration by outside ententes, whether on the basis of the khilafat movement or of pecuniary pacts.

Such like problems in our country become so difficult: because they are of the inside; the obstructions are all within our own mind, which is at once in revolt if there be any proposal for getting rid of them. That is why we feel so strongly attracted if some external solution be suggested. It is when his own character stands in the way of making a living along the beaten track, that a person becomes ready to court disaster in a desperate gamble for becoming suddenly rich. If our countrymen accept the proposition that the charkha is the principal means of attaining swaraj then it has to be admitted that in their opinion swaraj is an external achievement. And therein lies the reason why, when the defects of character and the perversions of social custom which obstruct its realisation are kept out of sight, and the whole attention is concentrated on home spun thread, no surprise is felt but rather relief.

If our countrymen accept the proposition that the charkha is the principal means of attaining swaraj then it has to be admitted that in their opinion swaraj is an external achievement. And therein lies the reason why, when the defects of character and the perversions of social custom which obstruct its realisation are kept out of sight, and the whole attention is concentrated on home spun thread, no surprise is felt but rather relief.

In these circumstances, if we take the view that the external poverty of our country claims our foremost attention—that one of the chief obstacles to swaraj will be removed if our cultivators employ their leisure in productive occupations, then it is for our leaders to think out the ways and means whereby such spare time may be utilised to the best advantage. And does it not then become obvious that such advantage is best to be secured in the line of cultivation itself?

Suppose that poverty should overtake me, then it would surely behove any adviser of mine, first of all to consider that literary work is the only one in which I can claim any length of practice. However great may be my mentor’s contempt for this profession, he cannot well ignore it in advising me on how to earn a living. He may be able to show by statistical calculations that a tea shop in the students quarters would yield 75% profit for accounts which neglect the human element easily run into large figures. And if such tea shop enterprise should but assist in completing my ruin, that is not because my intellect is of a lower order than that of the successful tea vendor, but because my mind is differently constituted.

It is not feasible to make the cultivator either happier or richer by thrusting aside, all of a sudden, the habits of body and mind which have grown upon him through his life. As I have indicated before, those who do not use their minds, get into fixed habits for which any the least novelty becomes an obstacle. If an undue love for a particular programme leads one to ignore this psychological truth, that makes no difference to psychology, it is the programme which suffers. In other agricultural countries the attempt is being successfully made to lead the cultivators towards a progressive improvement of production along the line of cultivation itself, and there agriculture has made long strides forward by an intelligent application of science, the yield per unit of land being many times larger than in our country. The path which is lit up by the intellect is not an easy, but a true path, the pursuit of which shows that manhood is at work. To tell the cultivator turn the charkha instead of trying to get him to employ his whole energy in his own line of work is only a sign of weakness. We cast the blame for being lazy on the cultivator, but the advice we give him amounts rather to a confession of the laziness of our own mind.

The discussion, so far, has proceeded on the assumption that the large-scale production of homespun thread and cloth will result in the alleviation of the country’s poverty. But after all that is a gratuitous assumption. Those who ought to know, have expressed grave doubts on the point. It is however better for an ignoramus like myself to refrain from entering into this controversy. My complaint is, that by the promulgation of this confusion between swaraj and charkha, the mind of the country is being distracted from swaraj.

My complaint is, that by the promulgation of this confusion between swaraj and charkha, the mind of the country is being distracted from swaraj.

We must have a clear idea of the vast thing that the welfare of our country means. To confine our idea of it to the outsides, or to make it too narrow, diminishes our own power of achievement. The lower the claim made on our mind, the greater the resulting depression of its vitality, the more languid does it become. To give the charkha the first place in our striving for the country’s welfare is only a way to make our insulted intelligence recoil in despairing inaction. A great and vivid picture of the country’s well-being in its universal aspect, held before our eyes, can alone enable our countrymen to apply the best of head and heart to carve out the way along which their varied activities may progress towards that end. If we make the picture petty, our striving becomes petty likewise. The great ones of the world who have made stupendous sacrifices for the land of their birth, or for their fellow-men in general, have all had a supreme vision of the welfare of country and humanity before their mind’s eye. If we desire to evoke self-sacrifice, then we must assist the people to meditate thus on a grand vision. Heaps of thread and piles of cloth do not constitute the subject of a great picture of welfare. That is the vision of a calculating mind; it cannot arouse those incalculable forces which, in the joy of a supreme realisation, cannot only brave suffering and death, but reck nothing, either, of obloquy and failure.

The child joyfully learns to speak, because from the lips of father and mother it get glimpses of language as a whole. Even while it understands but little, it is thereby continually stimulated and its joy is constantly at work in order to gain fullness of utterance. If, instead of having before it the exuberance of expression, the child had been hemmed in with grammar texts, it would have to be forced to learn its mother tongue at the point of the cane, and even then could not have done it so soon. It is for this reason I think that if we want the country to take up the striving for swaraj in earnest, then we must make an effort to hold vividly before it the complete image of that swaraj. I do not say that the propositions of this image can become the immensely large in a short space of time; but we must claim that it be whole, that it be true. All living things are organic wholes at every stage of their growth. The infant does not begin life at the toe-end and get its human shape only after some years of growth. That is why we can rejoice in it from the very first, and in that joy bear all the pains and sacrifices of helping it to grow. If Swaraj has to be viewed for any length of time, only as home-spun thread, that would be like having an infantile leg to nurse into maturity. A man like the Mahatma may succeed in getting some of our countrymen to take an interest in this kind of uninspiring nature for a time because of their faith in his personal greatness of soul. To obey him is for them an end in itself. To me it seems that such a state of mind is not helpful for the attainment of swaraj.

I think it to be primarily necessary that, in different places over the country small centers should be established in which expression is given to the responsibility of the country for achieving its own swaraj;—that is to say, its own welfare as a whole and not only in regard to its supply of homespun thread. The welfare of the people is a synthesis comprised of many elements, all intimately interrelated. To take them in isolation can lead to no real result. Health and work, reason, wisdom and joy, must all be thrown into the crucible in order that the result may be fullness of welfare. We want to see a picture of such welfare before our eyes, for that will teach us ever so much more than any amount of exhortation. We must have, before us, in various centres of population examples of different types of revived life abounding in health and wisdom and prosperity. Otherwise we shall never be able to bring about the realisation of what swaraj means simply by dint of spinning threads, weaving khaddar, or holding discourses. That which we would achieve for the whole of India must be actually made true even in some small corner of it,—then only will a worshipful striving for it be born in our hearts. Then only shall we know the real value of self-determination, na medhaya na bahudha srutena, not by reasoning nor by listening to lectures, but by direct experience. If even the people of one village of India, by the exercise of their own powers, make their village their very own, then and there will begin the work of realising our country as our own.

I think it to be primarily necessary that, in different places over the country small centers should be established in which expression is given to the responsibility of the country for achieving its own swaraj;—that is to say, its own welfare as a whole and not only in regard to its supply of homespun thread.

Fauna and flora take birth in their respective regions, but that does not make any such region belong to them. Man creates his own motherland. In the work of its creation as well as of its preservation, the people the country come into intimate relations with one another, and a country so created by them, they can love better than life itself. In our country its people are only born therein: they are taking no hand in its creation; therefore between them there are no deep-seated ties of connexion, nor is any loss sustained by the whole country felt as a personal loss by the individual. We must re-awaken the faculty of gaining the motherland by creating it. The various processes of creation need all the varied powers of man. In the exercise of these multifarious powers, along many and diverse roads, in order to reach one and the same goal, we may realise ourselves in our country. To be fruitful, such exercise of our powers must begin near home and gradually spread further and further outwards. If we are tempted to look down upon the initial stage of such activity as too small, let us remember the teaching of Gita: Swalpamasaya dharmosya travate mahato bhayat, by the least bit of dharma (truth) are we saved from immense fear. Truth is powerful, not in its dimensions, but in itself.

When acquaintance with, practice of, and pride in cooperative self-determination shall have spread in our land, then on such broad abiding foundation alone may swaraj become true. So long as we are wanting therein, both within and without and while such want is proving the root of all our other wants… want of food, of health, of wisdom,—it is past all belief that any programme of outward activity can rise superior to the poverty of spirit which has overcome our people. Success begets success; likewise swaraj alone can beget swaraj.

The right of God over the universe is His swaraj… the right to create it In that same privilege, I say consists our swaraj, namely our right to create our own country. The proof of such right, as well as its cultivation, lies in the exercise of the creative process. Only by living do we show that we have life.

It may be argued that spinning is also a creative act. But that is not so: for, by turning its wheel man merely becomes an appendage of the charkha‘, that is to say, he but does himself what a machine might have done: he converts his living energy into a dead turning movement. The machine is solitary, because being devoid of mind it is sufficient unto itself and knows nothing outside itself. Likewise alone is the man who confines himself to spinning, for the thread produced by his charkha is not for him a thread of necessary relationship with others. He has no need to think of his neighbour,—like the silkworm his activity is centred round himself. He becomes a machine, isolated, companionless. Members of Congress who spin may, while so engaged, dream of some economic paradise for their country, but the origin of their dream is elsewhere; the charkha has no spell from which such dreams may spring. But the man who is busy trying to drive out some epidemic from his village, even should he be unfortunate enough to be all alone in such endeavour, needs must concern himself with the interests of the whole village in the beginning, middle and end of his work, so that because of this very effort he cannot help realising within himself the village as a whole, and at every moment consciously rejoicing in its creation. In his work, therefore, does the striving for swaraj make a true beginning. When the others also come and join him, then alone can we say that the whole village is making progress towards the gain of itself which is the outcome of the creation of itself. Such gain may be called the gain of swaraj. However small the size of it may be, it is immense in its truth.

The village of which the people come together to earn for themselves their food, their health, their education, to gain for themselves the joy of so doing, shall have lighted a lamp on the way to swaraj. It will not be difficult therefrom to light others, one after another, and thus illuminate more and more of the path along which swaraj will advance, not propelled by the mechanical revolution of the charkha, but taken by the organic processes of its own living growth.

(It was after a couple of months that Gandhi wrote a rejoinder to Tagore’s ‘The Cult of the Charkha’ in his journal, Young India of 5 November 1925)

When (Sir) Rabindranath’s criticism of the charkha was published some time ago, several friends asked me to reply to it. Being heavily engaged I was unable then to study it in full. But I had read enough of it to know its trend. I was in no hurry to reply. Those who had read it were too much agitated or influenced to be able to appreciate what I might have then written even if I had the time. Now therefore is really the time for me to write on it and to ensure a dispassionate view being taken of the Poet’s criticism or my reply if such it may be called.

The criticism is a sharp rebuke to Acharya Ray for his impatience of the Poet’s and Acharya Seal’s position regarding the charkha, and a gentle rebuke to me for my exclusive love of it. Let the public understand that the Poet does not deny its great economic value. Let them know that he signed the appeal for the All India Deshabandhu Memorial after he had written his criticism. He signed the appeal after studying its contents carefully and even as he signed it he sent me the message that he had written something on the charkha, which might not quite please me. I knew therefore what was coming. But it has not displeased me. Why should mere disagreement with my views displease? If every disagreement were to displease, since no two men agree exactly on all points, life would be a bundle of unpleasant sensations and therefore a perfect nuisance. On the contrary, the frank criticism pleases me. For our friendship becomes all the richer for our disagreements. Friends to be friends are not called upon to agree even on most points. Only disagreement must have no sharpness, much less bitterness, about them. And I gratefully admit that there is none about the Poet’s criticism.

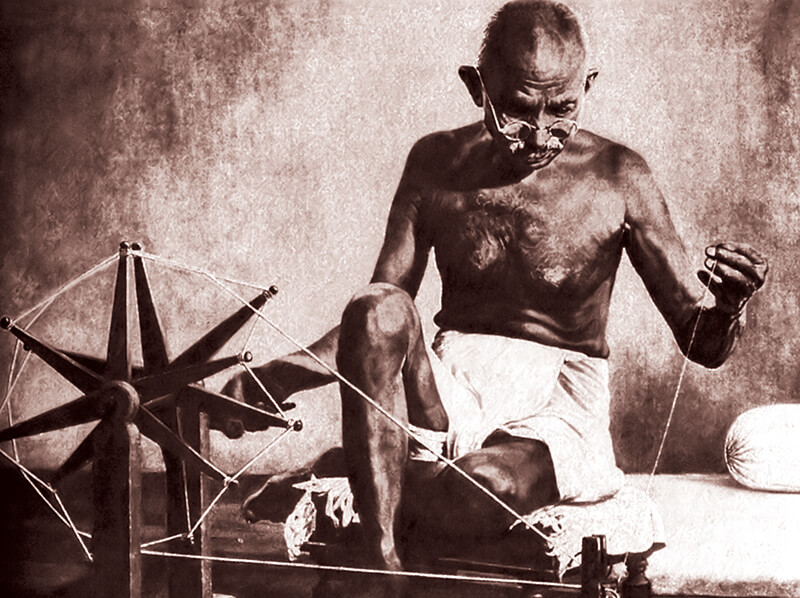

I am obliged to make these prefatory remarks as Dame Rumour has whispered that jealousy is the root of all that criticism. Such baseless suspicion betrays an atmosphere of weakness and intolerance. A little reflection must remove all ground for such a cruel charge. Of what should the Poet be jealous in pie? Jealousy presupposes the possibility of-rivalry. Well, I have never succeeded in writing a single rhyme in my life. There is nothing of the Poet about me. I cannot aspire after his greatness. He is the undisputed master of it. The world today does not possess his equal as a poet. My ‘Mahatmaship’ has no relation to the poet’s undisputed position. It is time to realise that our fields are absolutely different and at no point overlapping. The Poet lives in a magnificent world of his own creation—his world of ideas. I am a slave of somebody else’s creation—the spinning wheel. The Poet makes his gopis dance to the tune of his flute. I wander after my beloved Sita, the charkha and seek to deliver her from the ten-headed monster from Japan, Manchester, Paris etc. The Poet is an inventor—he creates, destroys and recreates. I am an explorer and having discovered a thing I must cling to it. The Poet presents the world with new and attractive things from day to day. I can merely show the hidden possibilities of old and even worn-out things. The world easily finds an honourable place for the magician who produces new and dazzling things. I have to struggle laboriously to find a corner for my worn-out things. Thus, there is no competition between us. But I may say in all humility that we complement each the other’s activity.

The fact is that the Poet’s criticism is a poetic licence and he who takes it literally is in danger of finding himself in an awkward corner. An ancient poet has said that Solomon arrayed in all his glory was not like one of the lilies of the field. He clearly referred to the natural beauty and innocence of the lily contrasted with the artificiality of Solomon’s glory and his sinfulness in spite of his many good deeds. Or take the poetical licence in it is easier for a camel to pass through the eye of a needle than for a rich man to enter the Kingdom of Heaven’. We know that no camel has ever passed through the eye of a needle and we know too that rich men like Janaka have entered the Kingdom of Heaven. Or take the beautiful simile of human teeth being likened to the pomegranate seed. Foolish women who have taken the poetical exaggeration literally have been found to disfigure and even harm their teeth. Painters and poets are obliged to exaggerate the proportions of their figures in order to give true perspective. Those therefore who take the Poet’s denunciation of the charkha literally will be doing an injustice to the Poet and an injury to themselves.

The fact is that the Poet’s criticism is a poetic licence and he who takes it literally is in danger of finding himself in an awkward corner.

The Poet does not, he is not expected, he has no need, to read Young India. All he knows about the movement is what he has picked up from table talk. He has therefore denounced what he has imagined to be the excesses of the charkha cult.

He thinks for instance that I want everybody to spin the whole of his or her time to the exclusion of all other activity; that is to say that I want the Poet to forsake his muse, the farmer his plough, the lawyer his brief and the doctor his lancet. So far is this from truth that I have asked no one to abandon his calling, but on the contrary to adorn it by giving every day only thirty minutes to spinning as sacrifice for the whole nation. I have indeed asked the famishing to spin for a living and the half-starved farmer to spin during his leisure hours to supplement his slender resources. If the Poet spun half an hour daily his poetry would gain in richness. For it would then represent the poor man’s wants and woes in a more forcible manner than now.

I have asked no one to abandon his calling, but on the contrary to adorn it by giving every day only thirty minutes to spinning as sacrifice for the whole nation. I have indeed asked the famishing to spin for a living and the half-starved farmer to spin during his leisure hours to supplement his slender resources. If the Poet spun half an hour daily his poetry would gain in richness. For it would then represent the poor man’s wants and woes in a more forcible manner than now.

The Poet thinks that the charkha is calculated to bring about a deathlike sameness in the nation and thus imagining he would shim it if he could. The truth is that the charkha is intended to realise the essential and living oneness of interest among India’s myriads. Behind the magnificent and kaleidoscopic variety, one discovers in nature a unity of purpose, design and form which is equally unmistakable. No two men are absolutely alike, not even twins, and yet there is much that is indispensable common to all mankind. And behind the commonness of form there is the same life pervading all. The idea of sameness or oneness was carried by Shankara to its utmost logical and natural limit and he exclaimed that there was only one Truth, one God Brahman, and all form, nam rupa was illusion or illusory, evanescent. We need not debate whether what we see is unreal; and whether the real behind the unreality is what we do not see. Let both be equally real if you will. All I say is that there is a sameness, identity or oneness behind the multiplicity and variety. And so do I hold that behind a variety of occupations there is an indispensable sameness also of occupation. Is not agriculture common to the vast majority of mankind? Even so was spinning common not long ago to a vast majority of mankind. Just as both prince and peasant must eat and clothe themselves, so must both labour for supplying their primary wants. Prince may do so if only by way of symbol and sacrifice but that much is indispensable for him if he will be true to himself and his people. Europe may not realise this vital necessity at the present moment, because it has made of exploitation of non- European races a religion. But it is a false religion bound to perish in the near future. The non-European races will not for ever allow themselves to be exploited. I have endeavoured to show a way out that is peaceful human and therefore noble. It may be rejected. If it is, the alternative is a tug of war, in which each will try to pull down the other. Then, when non-Europeans will seek to exploit the Europeans, the truth of the charkha will have to be realised. Just as, if we are to live, we must breathe not air imported from England nor eat food so imported, so may we not import cloth made in England. I do not hesitate to carry the doctrine to its logical limit and say that Bengal dare not import her cloth even from Bombay or from Banga Lakshmi. If Bengal will live her natural and free life without exploiting the rest of India or the world outside, she must manufacture her cloth in her own villages as she grows her corn there. Machinery has its place; it has come to stay. But it must not be allowed to displace the necessary human labour. An improved plough is a good thing. But if by some chance one man could plough up by some mechanical invention of his the whole of the land of India and control all the agricultural produce and if the millions had no other occupation, they would starve, and being idle, they would become dunces, as many have already become. There is hourly danger of many more being reduced to that unenviable state. I would welcome every improvement in the cottage machine but I know that it is criminal to displace the hand labour by the introduction of power-driven spindles unless one is at the same time ready to give millions of farmers some other occupation in their homes.

An improved plough is a good thing. But if by some chance one man could plough up by some mechanical invention of his the whole of the land of India and control all the agricultural produce and if the millions had no other occupation, they would starve, and being idle, they would become dunces, as many have already become.

The Irish analogy does not take us very far. It is perfect in so far as it enables us to realise the necessity of economic cooperation. But Indian circumstances being different, the method of working out cooperation is necessarily different. For Indian distress every effort at cooperation has to centre round the charkha if it is to apply to the majority of the inhabitants of this vast peninsula 1900 miles long and 1500 miles broad. A Sir Gangaram may give us a model farm which can be no model for the penniless Indian farmer who has hardly two to three acres of land which every day runs the risk of being still further cut up.

Round the charkha, that is, amidst the people who have shed their idleness and who have understood the value of cooperation, a national servant would build up a programme of anti-malaria campaign, improved sanitation, settlement of village disputes, conservation and breeding of cattle and hundreds of other beneficial activities. Wherever charkha work is fairly established, all such ameliorative activity is going on according to the capacity of the villagers and the workers concerned.