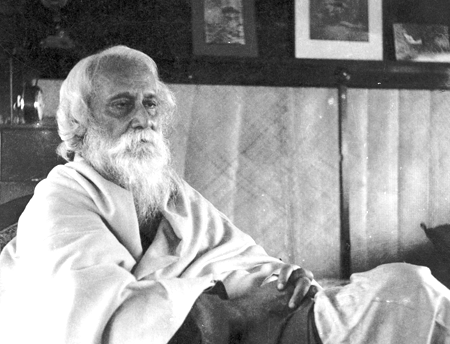

Rabindranath Tagore expressed his views on nationalism on many occasions. A collection of his three prominent essays on this theme were published in 1917 in a book titled ‘Nationalism’ (we have republished one of these essays). According to him, a nation, “in the sense of the political and economic union of the people, is that aspect, which a whole population assumes when organized for a mechanical purpose.”

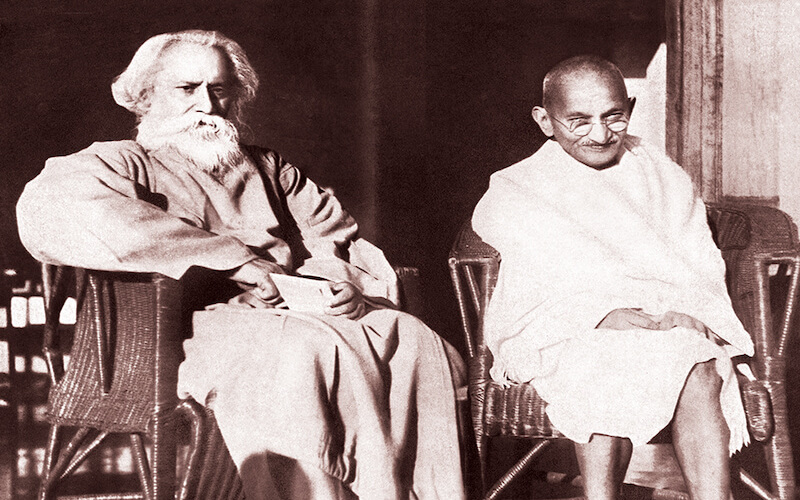

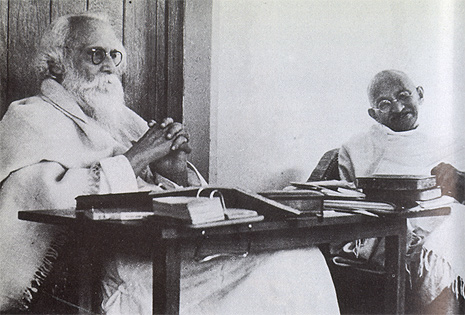

Referring to a nation as a man-made ‘machine’, Tagore argues that the true spirit of nationalism lies in its broad humanistic concern rather than constrained political expediency. It is in this context that we see Tagore being at odds with Gandhi’s call for non-cooperation because, according to Tagore, the very idea of non-cooperation breeds negation. For Tagore, “the spirit of rejection finds its support in the consciousness of separateness, the spirit of acceptance in the consciousness of unity.” Tagore’s idea of Swaraj was never bound by territorial boundaries. Emphasizing the need to establish a “harmony between the physical and spiritual nature of man,” Tagore believes in the law of cooperation and the “true meeting of the East and the West.” “Love,” he says, “is the ultimate truth of soul… The idea of non-cooperation unnecessarily hurts that truth… ” Tagore presents a sharp critique of those who celebrate the “national carnivals of materialism” ultimately ignoring the “laws of moral health”. The aspirations of a people to achieve self-governance in a country are rooted, according to him, in a materialistic world, which he refers to as organizations made up of “National Egoism”. He adds, “It lies in the power of the materially weak to save the world from this illusion and India, in spite of her penury and humiliation, can afford to come to the rescue of humanity.” A believer in the idea of humanistic values, Tagore was critical of the militaristic and imperialistic attitudes that Swaraj gave birth to. Raising a cry for disarmament, on the path of seeking ‘truth’, he argues “that moral force is a higher power than brute force, will be proved by the people who are unarmed.” The destiny of India, he illustrates, “has chosen for its ally, Narayan [the power of the soul], and not the Narayani Sena [the power of the muscle].” To reinforce his reservations against non-cooperation, Tagore contrasts mukti (emancipation, as the object of Brahma-vidya) and nirvana (extinction, as preached in Buddhism): “Mukti draws our attention to the positive [emphasis on ananda (joy)], and nirvana to the negative side of truth [emphasis on avoiding dukkha (misery)].” In a similar vein, referring to non-cooperation as “political asceticism”, he argues that when students sacrifice their education in support of non-cooperation, they are not striving “to a fuller education, but to non-education.” He adds further, “the anarchy of a mere emptiness never tempts me, even when it is resorted to as a temporary measure.” Gandhi, in his reply to the Poet’s “horror of everything negative”, argues that “rejection is as much an ideal as the acceptance of a thing… All religions teach that two opposite forces act upon us and that the human endeavour consists in a series of eternal rejections and acceptances. Non-cooperation with evil is as much a duty as co-operation with good.” Pointing out Tagore’s analysis of Buddha’s nirvana as unjust, Gandhi adds that “mukti is as much a negative state as nirvana… the final word of the Upanishads (Brahma-vidya) is Not. Neti was the best description the authors of the Upanishads were able to find for Brahma.” In favour of his ideal, i.e. Swaraj, Gandhi argues that the non-cooperation movement is meant to alter the meanings of nationalism and patriotism and extend their scope. Taking the example of language, he highlights the political and commercial significance given to English, a foreign language, as opposed to vernacular languages. So much so that education is being equated with the knowledge of English. Pitying the condition of the vernaculars, then, Gandhi remarks, “All these are for me signs of our slavery and degradation. It is unbearable to me that the vernaculars should be crushed and starved as they have been… I refuse to live in other people’s houses as an interloper, a beggar or a slave.” Disagreeing with Tagore’s understanding of the movement, Gandhi goes on to question the former’s judgment of the “movement or reformation, purification and patriotism spelt humanity.” It is wrong, he argues, “to judge Non-cooperation by the students’ misconduct in London or Malegaon’s in India, as it would be to judge Englishmen by the Dyers or the O’Dwyers.” Gandhi also answers Tagore’s “anxiety” regarding the negation of cooperation in the movement by explaining his thoughts that went into the conception of this movement. “The present struggle,” Gandhi writes, “is being waged against compulsory cooperation, against one-sided combination, against the armed imposition of modern methods of exploitation, masquerading under the name of civilization. Non-cooperation is a protest against an unwitting and unwilling participation in evil.” Tagore, however, maintains his stand against the movement by arguing that Swaraj “is maya”. To gain Swaraj, he says, one’s fight should be a spiritual fight. The “alien government,” that India is fighting against, is, according to Tagore, “a veritable chameleon”. Since this foreign power will keep changing its guise even after the Englishmen leave India, the goal of a person should be to gain the truth within himself. Tagore, thus, lays emphasis “on the truth, that we must win our country, not from some foreigner, but from our own inertia, our own indifference.” Tagore praises Gandhi’s “truth of love” in bringing together masses of the country but he also expresses his reservations against Gandhi’s idea of “spinning and weaving” as the means to achieve Swaraj. Using or refusing clothes of a particular manufacture, according to Tagore, is a question answered best by economics. The burnt clothes, “heaped up before the very eyes of our motherland shivering and ashamed in her nakedness”, negates the idea of ‘ethics’ against ‘economics’ as propounded by Gandhi. “Swaraj is not concerned with our apparel only—it cannot be established on cheap clothing; its foundation is in the mind, which, with its diverse powers and its confidence in those powers, goes on all the time creating swaraj for itself.” Gandhi nevertheless asserts that Tagore’s dream of attaining swaraj will come true “only by Non-violent Non-cooperation… Non-cooperation is intended to give the very meaning to patriotism that the Poet is yearning after. An India prostrate at the feet of Europe can give no hope to humanity. An India awakened and free has a message of peace and goodwill to a groaning world. Non-cooperation is designed to supply her with a platform from which she will preach the message.” Read the original texts of this remarkable exchange between the two, in full, below. This is the first of a series of debates that we will carry, between Indian leaders and thinkers who have defined history with their ideas.

(The Calcutta journal Modern Review of May 1921 carried letters inspired by Gandhi’s Non-cooperation movement; addressed to C.F. Andrews, London, 1928)

Your last letter gives wonderful news about our students in Calcutta. I hope that this spirit of sacrifice and willingness to suffer will grow in strength; for to achieve this is an end in itself. This is the true freedom! Nothing is of higher value be it national wealth, or independence, than disinterested faith in ideals, in the moral greatness of man. The West has its unshakable faith in material strength and prosperity; and therefore however loud grows the cry for peace and disarmament, its ferocity grows louder, gnashing its teeth and lashing its tail in impatience. It is like a fish, hurt by the pressure of the flood, planning to fly in the air. Certainly the idea is brilliant, but it is not possible for a fish to realize.

We, in India, shall have to show to the world, what is that truth, which not only makes disarmament possible but turns it into strength. That moral force is a higher power than brute force, will be proved by the people who are unarmed. Life, in its higher development, has thrown off its tremendous burden of armour and a prodigious quantity of flesh; till man has become the conqueror of the brute world. The day is sure to come, when the frail man of spirit, completely unhampered by arms and air fleets, and dreadnoughts will prove that the meek is to inherit the earth. It is in the fitness of things, that Mahatma Gandhi, frail in body and devoid of all material resources, should call up the immense power of the meek, that has been lying waiting in the heart of the destitute and insulted humanity of India. The destiny of India has chosen for its ally, Narayan, and not the Narayansena—the power of soul and not that of muscle. And she is to raise the history of man, from the muddy level of physical conflict to the higher moral altitude. What is swaraj! It is maya, it is like a mist, that will vanish leaving no stain on the radiance of the Eternal. However we may delude ourselves with the phrases learnt from the West, Swaraj is not our objective.

The destiny of India has chosen for its ally, Narayan, and not the Narayansena—the power of soul and not that of muscle. And she is to raise the history of man, from the muddy level of physical conflict to the higher moral altitude. What is swaraj! It is maya, it is like a mist, that will vanish leaving no stain on the radiance of the Eternal. However we may delude ourselves with the phrases learnt from the West, Swaraj is not our objective.

Our fight is a spiritual fight, it is for Man. We are to emancipate Man from the meshes that he himself has woven round him,—these organisations of National Egoism. The butterfly will have to be persuaded that the freedom of the sky is of higher value than the shelter of the cocoon. If we can defy the strong, the armed, the wealthy, revealing to the world power of the immortal spirit, the whole castle of the Giant Flesh will vanish in the void. And then Man will find his Swaraj. We, the famished, ragged ragamuffins of the East, are to win freedom for all Humanity. We have no word for Nation in our language. When we borrow this word from other people, it never fits us. For we are to make our league with Narayan, and our victory will not give us anything but victory itself; victory for God’s world. I have seen the West; I covet not the unholy feast, in which she revels every moment, growing more and more bloated and red and dangerously delirious. Not for us, is this mad orgy of midnight, with lighted torches, but awakenment in the serene light of morning.

Lately I have been receiving more and more news and newspaper cuttings from India, giving rise in my mind to a painful struggle that presages a period of suffering which is waiting for me. I am striving with all my power to tune my mood of mind to be in accord with the great feeling of excitement sweeping across my country. But deep in my being why is there this spirit of resistance maintaining its place in spite of my strong desire to remove it? I fail to find a clear answer and through my gloom of dejection breaks out a smile and a voice saying, “Your place is on the seashore of worlds with children; there is your peace, and I am with you there.”

And this is why lately I have been playing with inventing new metres. These are merest nothings that are content to be borne away by the current of time, dancing in the sun and laughing as they disappear. But while I play the whole creation is amused, for are not flowers and leaves never ending experiments in metre? Is not my God an eternal waster of time? He flings stars and planets in the whirlwind of changes, he floats paper boats of ages, filled with his fancies, on the rushing stream of appearance. When I tease him and beg him to allow me to remain his little follower and accept a few trifles of mine as the cargo of his playboat he smiles and I trot behind him catching the hem of his robe.

But where am I among the crowd, pushed from behind, pressed from all sides? And what is this noise about me? If it is a song, then my own sitar can catch the time and I join in the chorus, for I am a singer. But if it is a shout, then my voice is wrecked and I am lost in bewilderment. I have been trying all these days to find in it a melody, straining my ear, but the idea of non-cooperation with its mighty volume of sound does not sing to me, its congregated menace of negations shouts. And I say to myself, “If you cannot keep step with your countrymen at this great Crisis of their history, never say that you are right and the rest of them wrong; only give up your role as a soldier, go back to your corner as a poet, be ready to accept popular derision and disgrace”.

I have been trying all these days to find in it a melody, straining my ear, but the idea of non-cooperation with its mighty volume of sound does not sing to me, its congregated menace of negations shouts. And I say to myself, “If you cannot keep step with your countrymen at this great Crisis of their history, never say that you are right and the rest of them wrong; only give up your role as a soldier, go back to your corner as a poet, be ready to accept popular derision and disgrace”.

R, in support of the present movement, has often said to me that passion for rejection is a stronger power in the beginning than the acceptance of an ideal. Though I know it to be a fact, I cannot take it as a truth. We must choose our allies once for all, for they stick to us even when we would be glad to be rid of them. If we once claim strength from intoxication, then in the time of reaction our normal strength is bankrupt, and we go back again and again to the demon who lends us resources in a vessel whose bottom it takes away.

Brahma-vidya (the cult of Brahma, the Infinite Being) in India has for its object mukti, emancipation, while Buddhism has nirvana, extinction. It may be argued that both have the same idea in different names. But names represent attitudes of mind, emphasise particular aspects of truth. Mukti draws our attention to the positive, and nirvana to the negative side of truth.

Buddha kept silence all through his teachings about the truth of the Om, the everlasting yes, his implication being that by the negative path of destroying the self we naturally reach that truth. Therefore he emphasised the fact of dukkha (misery) which had to be avoided and the Brahma-vidya emphasised the fact of ananda, joy, which had to be attained. The latter cult also needs for its fulfillment the discipline of self-abnegation, but it holds before its view the idea of Brahma, not only at the end but all through the process of realisation. Therefore, the idea of life’s training was different in the Vedic period from that of the Buddhistic. In the former it was the purification of life’s joy, in the latter it was the eradication of it. The abnormal type of asceticism to which Buddhism gave rise in India revelled in celibacy and mutilation of life in all different forms. But the forest life of the Brahmana was not antagonistic to the social life of man, but harmonious with it. It was like our musical instrument tambura whose duty is to supply the fundamental notes to the music to save it from straying into discordance. It believed in anandam, the music of the soul, and its own simplicity was not to kill it but to guide it.

The idea of non-cooperation is political asceticism. Our students are bringing their offering of sacrifices to what? Not to a fuller education but to non-education. It has at its back a fierce joy of annihilation which at best is asceticism, and at its worst is that orgy of frightfulness in which the human nature, losing faith in the basic reality of normal life, finds a disinterested delight in an unmeaning devastation as has been shown in the late war and on other occasions which came nearer to us. No, in its passive moral form is asceticism and in its active moral form is violence. The desert is as much a form of a himsa (malignance) as is the raging sea in storms, they both are against life.

The idea of non-cooperation is political asceticism. Our students are bringing their offering of sacrifices to what? Not to a fuller education but to non-education. It has at its back a fierce joy of annihilation which at best is asceticism, and at its worst is that orgy of frightfulness in which the human nature, losing faith in the basic reality of normal life, finds a disinterested delight in an unmeaning devastation as has been shown in the late war and on other occasions which came nearer to us. No, in its passive moral form is asceticism and in its active moral form is violence. The desert is as much a form of a himsa (malignance) as is the raging sea in storms, they both are against life.

I remember the day, during the swadeshi movement in Bengal, when a crowd of young students came to see me in the first floor hall of our Vichitra House. They said to me that if I would order them to leave their schools and colleges they would instantly obey. I was emphatic in my refusal to do so, and they went away angry, doubting the sincerity of my love for my motherland. And yet long before this popular ebullition of excitement I myself had given a thousand rupees, when I had not five rupees to call my own, to open a swadeshi store and courted banter and bankruptcy. The reason of my refusing to advise those students to leave their schools was because the anarchy of a mere emptiness never tempts me, even when it is resorted to as a temporary measure. I am frightened of an abstraction which is ready to ignore living reality. These students were no more phantoms to me; their life was a great fact to them and to the All. I could not lightly take upon myself the tremendous responsibility of a mere negative programme for them which would uproot their life from its soil, however thin and poor that soil might be.

The great injury and injustice which had been done to those boys who were tempted away from their career before any real provision was made, could never be made good to them. Of course that is nothing from the point of view of an abstraction which can ignore the infinite value even of the smallest fraction of reality. I wish I were the little creature Jack whose one mission is to kill the giant abstraction which is claiming the sacrifice of individuals all over the world under highly painted masks of delusion.

I say again and again that I am a poet, that I am not a fighter by nature. I would give everything to be one with my surroundings. I love my fellow beings and I prize their love. Yet I have been chosen by destiny to ply my boat there where the current is against me. What irony of fate is this that I should be preaching cooperation of cultures between East and West on this side of the sea just at the moment when the doctrine of non-cooperation is preached on the other side?

You know that I do not believe in the material civilisation of the West just as I do not believe in the physical body to be the highest truth in man. But I still less believe in the destruction of the physical body, and the ignoring of the material necessities of life. What is needed is establishment of harmony between the physical and spiritual nature of man, maintaining of balance between the foundation and superstructure. I believe in the true meeting of the East and the West. Love is the ultimate truth of soul. We should do all we can, not to outrage that truth, to carry its banner against all opposition. The idea of non-cooperation unnecessarily hurts that truth. It is not our heart fire but the fire that burns out our hearth and home.

What is needed is establishment of harmony between the physical and spiritual nature of man, maintaining of balance between the foundation and superstructure. I believe in the true meeting of the East and the West. Love is the ultimate truth of soul. We should do all we can, not to outrage that truth, to carry its banner against all opposition. The idea of non-cooperation unnecessarily hurts that truth. It is not our heart fire but the fire that burns out our hearth and home.

Things that are stationary have no responsibility and need no law. For death, even the tombstone is a useless luxury. But for a world, which is an ever-moving multitude advancing towards an idea, all its laws must have one principle of harmony. This is the law of creation.

Man became great when he found out this law for himself, the law of co-operation. It helped him to move together, to utilise the rhythm and impetus of the world march. He at once felt that this moving together was not mechanical, not an external regulation for the sake of some convenience. It was what the metre is in poetry, which is not a mere system of enclosure for keeping ideas from running away in disorder, but for vitalising them, making them indivisible in a unity of creation.

So far this idea of co-operation has developed itself into individual communities within the boundaries of which peace has been maintained and varied wealth of life produced. But outside these boundaries the law of co-operation has not been realised. Consequently the great world of man is suffering from ceaseless discordance. We are beginning to discover that our problem is world-wide and no one people of the earth can work out its salvation by detaching itself from the others. Either we shall be saved together, or drawn together into destruction.

This truth has ever been recognised by all the great personalities of the world. They had in themselves the perfect consciousness of the undivided spirit of man. Their teachings were against tribal exclusiveness, and thus we find that Buddha’s India transcended geographical India and Christ’s religion broke through the bonds of Judaism.

Today, at this critical moment of the world’s history cannot India rise above her limitations and offer the great ideal to the world that will work towards harmony and co-operation between the different peoples of the earth! Men of feeble faith will say that India requires being strong and rich before she can raise her voice for the sake of the whole world. But I refuse to believe it. That the measure of man’s greatness is in his material resources is a gigantic illusion casting its shadow over the present day world, it is an insult to man. It lies in the power of the materially weak to save the world from this illusion and India, in spite of her penury and humiliation, can afford to come to the rescue of humanity.

Today, at this critical moment of the world’s history cannot India rise above her limitations and offer the great ideal to the world that will work towards harmony and co-operation between the different peoples of the earth! Men of feeble faith will say that India requires being strong and rich before she can raise her voice for the sake of the whole world. But I refuse to believe it. That the measure of man’s greatness is in his material resources is a gigantic illusion casting its shadow over the present day world, it is an insult to man. It lies in the power of the materially weak to save the world from this illusion and India, in spite of her penury and humiliation, can afford to come to the rescue of humanity.

The freedom of unrestrained egoism in the individual is licence and not true freedom. For his truth is in that which is universal in him. Individual human races also attain true freedom when they have the freedom of perfect revelation of Man and not that of their aggressive racial egoism. The idea of freedom which prevails in modern civilisation is superficial and materialistic. Our revolution in India will be a true one when its forces will be directed against this crude idea of liberty.

The sunlight of love has the freedom that ripens the wisdom of immortal life, but passions’ fire can only forge fetters for ourselves. The spiritual Man has been struggling for its emergence into perfection, and all true cry of freedom is for this emancipation. Erecting barricades of fierce separateness in the name of national necessity is offering hindrance to it, therefore in the long run building a prison for the nation itself. For the only path of deliverance for nations is in the ideal humanity.

Creation is an endless activity of God’s freedom; it is an end in itself. Freedom is true when it is a revelation of truth. Man’s freedom is for the revelation of the truth of Man which is struggling to express itself. We have not yet fully realised it. But those people who have faith in its greatness, who acknowledge its sovereignty, and have the instinctive urging in their heart to break down obstructions, are paving the way for its coming.

India ever has nourished faith in the truth of spiritual man for whose realisation she has made innumerable experiments, sacrifices and penance, some verging on the grotesque and the abnormal. But the fact is, she has never ceased in her attempt to find it even though at the tremendous cost of material success.

Therefore I feel that the true India is an idea and not a mere geographical fact. I have come into touch with this idea in far away places of Europe and my loyalty was drawn to it in persons who belonged to different countries from mine. India will be victorious when this idea wins victory,—the idea of ‘Purusham mahantam aditya-varnam tamasah parastat’, the Infinite Personality whose light reveals itself through the obstruction of darkness. Our fight is against this darkness, our object is the revealment of the light of this Infinite Personality in ourselves. This Infinite Personality of man is not to be achieved in single individuals, but in one grand harmony of all human races. The darkness of egoism which will have to be destroyed is the egoism of the People. The idea of India is against the intense consciousness of the separateness of one’s own people from others, and which inevitably leads to ceaseless conflicts. Therefore my one prayer is: let India stand for the cooperation of all peoples of the world. The spirit of rejection finds its support in the consciousness of separateness, the spirit of acceptance in the consciousness of unity.

India has ever declared that Unity is Truth, and separateness is maya. This unity is not a zero, it is that which comprehends all and therefore can never be reached through the path of negation. Our present struggle to alienate our heart and mind from those of the West is an attempt at spiritual suicide. If in the spirit of national vain-gloriousness we shout from our house-tops that the West has produced nothing that has an infinite value for man, then we but create a serious cause of doubt about the worth of any product of the Eastern mind. For it is the mind of Man in the East and West which is ever approaching Truth in her different aspects from different angles of vision; and if it can be true that the standpoint of the West has betrayed it into an utter misdirection, then we can never be sure of the standpoint of the East. Let us be rid of all false pride and rejoice at any lamp being lit at any corner of the world, knowing that it is a part of the common illumination of our house.

India has ever declared that Unity is Truth, and separateness is maya. This unity is not a zero, it is that which comprehends all and therefore can never be reached through the path of negation. Our present struggle to alienate our heart and mind from those of the West is an attempt at spiritual suicide. If in the spirit of national vain-gloriousness we shout from our house-tops that the West has produced nothing that has an infinite value for man, then we but create a serious cause of doubt about the worth of any product of the Eastern mind. For it is the mind of Man in the East and West which is ever approaching Truth in her different aspects from different angles of vision; and if it can be true that the standpoint of the West has betrayed it into an utter misdirection, then we can never be sure of the standpoint of the East. Let us be rid of all false pride and rejoice at any lamp being lit at any corner of the world, knowing that it is a part of the common illumination of our house.

The other day I was invited to the house of a distinguished art critic of America who is a great admirer of old Italian art. I questioned him if he knew anything of our Indian pictures and brusquely said that most probably he would “hate them”. I suspected he had seen some of them and hated them. In retaliation I could have said something in the same language about the Western art. But I am proud to say it was not possible for me. For I always try to understand the Western art and never to hate it. Whatever we understand and enjoy in human products instantly becomes ours wherever they might have their origin. I should feel proud of my humanity when I can acknowledge the poets and artists of other countries as mine own. Let me feel with unalloyed gladness that all the great glories of man are mine.

Therefore, it hurts me deeply when the cry of rejection rings loud against the West in my country with the clamour that the Western education can only injure us. It cannot be true. What has caused the mischief is the fact that for a long time we have been out of touch with our own culture and therefore the Western culture has not found its prospective in our life very often found a wrong prospective giving our mental eye a squint. When we have the intellectual capital of our own, the commerce of thought with the outer world becomes natural and fully profitable. But to say that such commerce is inherently wrong, is to encourage the worst form of provincialism, productive of nothing but intellectual indigence. The West has misunderstood the East which is at the root of the disharmony that prevails between them, but will it mend the matter if the East in her turn tries to misunderstand the West? The present age has powerfully been possessed by the West; it has only become possible because to her is given some great mission for man. We from the East have to come to her to learn whatever she has to teach us; for by doing so we hasten the fulfillment of this age. We know that the East also has her lessons to give and she has her own responsibility of not allowing her light to be extinguished, and the time will come when the West will find leisure to realise that she has a home of hers in the East where her food is and her rest.

(Gandhi’s Young India of 1 June 1921, carried a reply to the Poet’s musings, under the heading ‘English Learning’)

Elsewhere the reader will see my humble endeavour in reply to Dr. Tagore’s criticism of Non-cooperation. I have since read his letter to the Manager of Santiniketan. I am sorry to observe that the letter is written in anger and in ignorance of facts. The Poet was naturally incensed to find that certain students in London would not give a hearing to Mr. Pearson, one of the truest of Englishmen, and he became equally incensed to learn that I had told our women to stop English studies. The reasons for my advice, the Poet evidently inferred for himself.

How much better it would have been, if he had not imputed the rudeness of the students to Non-cooperation, and had remembered that Non-cooperators worship Andrews, honour Stokes, and gave a most respectful hearing to Messrs. Wedgwood Benn, Spoor and Holford Knight at Nagpur, that Maulana Mahomed Ali accepted the invitation to tea of an English official when he invited him as a friend, that Hakim Ajmalkhan, a staunch Non-cooperator, had the portraits of Lord and Lady Hardinge unveiled in his Tibbia College and had invited his many English friends to witness the ceremony. How much better it would have been, if he had refused to allow the demon doubt to possess him for one moment, as to the real and religious character of the present movement, and had believed that the movement was altering the meaning of old terms, nationalism and patriotism, and extending their scope.

If he, with a poet’s imagination, had seen that I was incapable of wishing to cramp the mind of the Indian women, and I could not object to English learning as such, and recalled the fact that throughout my life I had fought for the fullest liberty for women, he would have been saved the injustice which he has done me, and which, I know, he would never knowingly do to an avowed enemy.

The Poet does not know perhaps that English is today studied because of its commercial and so-called political value. Our boys think, and rightly in the present circumstances, that without English they cannot get Government service. Girls are taught English as a passport to marriage. I know several instances of women wanting to learn English so that they may be able to talk to Englishmen in English. I know husbands who are sorry that their wives cannot talk to them and their friends in English. I know families in which English is being made the mother tongue. Hundreds of youths believe that without a knowledge of English freedom for India is practically impossible. The canker has so eaten into the society that, in many cases, the only meaning of Education is a knowledge of English.

All these are for me signs of our slavery and degradation. It is unbearable to me that the vernaculars should be crushed and starved as they have been. I cannot tolerate the idea of parents writing to their children, or husbands writing to their wives, not in their own vernaculars, but in English. I hope I am as great a believer in free air as the great Poet. I do not want my house to be walled in on all sides and my windows to be stuffed.

I want the cultures of all the lands to be blown about my house as freely as possible. But I refuse to be blown off my feet by any. I refuse to live in other people’s houses as an interloper, a beggar or a slave. I refuse to put the unnecessary strain of learning English upon my sisters for the sake of false pride or questionable social advantage. I would have our young men and young women with literary tastes to learn as much of English and other world-languages as they like, and then expect them to give the benefits of their learning to India and to the world, like a Bose, a Roy or the Poet himself.

I want the cultures of all the lands to be blown about my house as freely as possible. But I refuse to be blown off my feet by any. I refuse to live in other people’s houses as an interloper, a beggar or a slave. I refuse to put the unnecessary strain of learning English upon my sisters for the sake of false pride or questionable social advantage. I would have our young men and young women with literary tastes to learn as much of English and other world-languages as they like, and then expect them to give the benefits of their learning to India and to the world, like a Bose, a Roy or the Poet himself.

But I would not have a single Indian to forget, neglect or be ashamed of his mother-tongue, or to feel that he or she cannot think or express the best thoughts in his or her own vernacular. Mine is not a religion of the prison house. It has room for the least among God’s creation. But it is proof against insolence, pride of race, religion or colour. I am extremely sorry for the Poet’s misreading of this great movement or reformation, purification and patriotism spelt humanity. If he will be patient, he will find no cause for sorrow or shame for his countrymen. I respectfully warn him against mistaking its excrescences for the movement itself. It is as wrong to judge Non-cooperation by the students’ misconduct in London or Malegaon’s in India, as it would be to judge Englishmen by the Dyers or the O’Dwyers.

(Young India of 1 June 1921 also carried another reply to Tagore from Gandhi on cooperation and non-cooperation vis-a-vis the students.)

The Poet of Asia, as Lord Hardinge called Dr. Tagore, is fast becoming, if he has not already become, the Poet of the world. Increasing prestige has brought to him increasing responsibility. His greatest service to India must be his poetic interpretation of India’s message to the world. The Poet is, therefore, sincerely anxious that India should deliver no false or feeble message in her name. He is naturally jealous of his country’s reputation. He says he has striven hard to find himself in tune with the present movement. He confesses that he is baffled. He can find nothing for his lyre in the din and the bustle of Non-cooperation. In three forceful letters, he has endeavoured to give expression to his misgivings, and he has come to the conclusion that Non-cooperation is not dignified enough for the India of his vision, that it is a doctrine of negation and despair. He fears that it is a doctrine of separation, exclusiveness, narrowness and negation.

No Indian can feel anything but pride in the Poet’s exquisite jealousy of India’s honour. It is good that he should have sent to us his misgivings in language at once beautiful and clear.

In all humility, I shall endeavour to answer the Poet’s doubts. I may fail to convince him or the reader who may have been touched by his eloquence, but I would like to assure him and India that Non-cooperation in conception is not any of the things he fears, and he need have no cause to be ashamed of his country for having adopted Non-cooperation. If, in actual application, it appears in the end to have failed, it will be no more the fault of the doctrine, than it would be of Truth, if those who claim to apply it in practice do not appear to succeed. Non-cooperation may have come in advance of its time. India and the world must then wait, but there is no choice for India save between violence and Non-cooperation.

Nor need the Poet fear that Non-cooperation is intended to erect a Chinese wail between India and the West. On the contrary, Non-cooperation is intended to pave the way to real, honourable and voluntary co-operation based on mutual respect and trust.

The present struggle is being waged against compulsory cooperation, against one-sided combination, against the armed imposition of modern methods of exploitation, masquerading under the name of civilisation.

Non-cooperation is a protest against an unwitting and unwilling participation in evil.

Non-cooperation is intended to pave the way to real, honourable and voluntary co-operation based on mutual respect and trust. The present struggle is being waged against compulsory cooperation, against one-sided combination, against the armed imposition of modern methods of exploitation, masquerading under the name of civilisation. Non-cooperation is a protest against an unwitting and unwilling participation in evil.

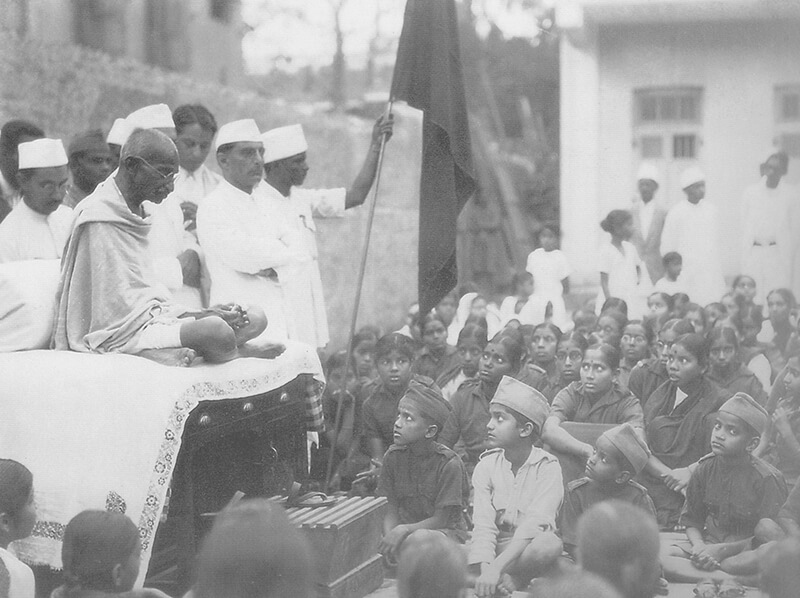

The Poet’s concern is largely about the students. He is of the opinion that they should not have been called upon to give up Government schools before they had other schools to go to. Here I must differ from him. I have never been able to make a fetish of literary training. My experience has proved to my satisfaction that literary training by itself adds not an inch to one’s moral height and that character-building is independent of literary training. I am firmly of the opinion that the Government schools have unmanned us; rendered us helpless and Godless. They have filled us with discontent, and providing no remedy for the discontent, have made us despondent. They have made us what we were intended to become — clerks and interpreters. A Government builds its prestige upon the apparently voluntary association of the governed. And if it was wrong to cooperate with the Government in keeping us slaves, we were bound to begin with those institutions in which our association appeared to be most voluntary. The youth of a nation are its hope. I hold that, as soon as we discovered that the system of Government was wholly, or mainly evil, it became sinful for us to associate our children with it.

It is no argument against the soundness of the proposition laid down by me that the vast majority of the students went back after the first flush of enthusiasm. Their recantation is proof rather of the extent of our degradation than of the wrongness of the step. Experience has shown that the establishment of national schools has not resulted in drawing many more students. The strongest and the truest of them came out without any national schools to fall back upon, and I am convinced that these first withdrawals are rendering service of the highest order.

But the Poet’s protest against the calling out of the boys is really a corollary to his objection to the very doctrine of Non-cooperation. He has a horror of everything negative. His whole soul seems to rebel against the negative commandments of religion. I must give his objection in his own inimitable language.

“R, in support of the present movement has often said to me that passion for rejection is a stronger power in the beginning than the acceptance of an ideal. Though I know it to be a fact, I cannot take it as a truth… Brahma-vidya in India has for its object mukti (emancipation), while Buddhism has nirvana (extinction), negative side of truth… Therefore, he (Buddha) emphasised the fact of dukkha (misery) which had to be avoided and the Brahma-vidya emphasised the fact of anand (joy) which had to be attained.” In these and kindred passages, the reader will find the key to the Poet’s mentality. In my humble opinion, rejection is as much an ideal as the acceptance of a thing. It is as necessary to reject untruth as it is to accept truth. All religions teach that two opposite forces act upon us and that the human endeavour consists in a series of eternal rejections and acceptances. Non- cooperation with evil is as much a duty as co-operation with good. I venture to suggest that the Poet has done an unconscious injustice to Buddhism in describing nirvana as merely a negative state. I make bold to say that mukti (emancipation) is as much a negative state as nirvana. Emancipation from or extinction of the bondage of the flesh leads to ananda (eternal bliss). Let me close this part of my argument by drawing attention to the fact that the final word of the Upanishads (Brahma-vidya) is Not. Neti was the best description the authors of the Upanishads were able to find for Brahma.

In my humble opinion, rejection is as much an ideal as the acceptance of a thing. It is as necessary to reject untruth as it is to accept truth. All religions teach that two opposite forces act upon us and that the human endeavour consists in a series of eternal rejections and acceptances. Non- cooperation with evil is as much a duty as co-operation with good. I venture to suggest that the Poet has done an unconscious injustice to Buddhism in describing nirvana as merely a negative state. I make bold to say that mukti (emancipation) is as much a negative state as nirvana. Emancipation from or extinction of the bondage of the flesh leads to ananda (eternal bliss). Let me close this part of my argument by drawing attention to the fact that the final word of the Upanishads (Brahma-vidya) is Not. Neti was the best description the authors of the Upanishads were able to find for Brahma.

I, therefore, think that the Poet has been unnecessarily alarmed at the negative aspect of Non-cooperation. We had lost the power of saying ‘no’. It had become disloyal, almost sacrilegious to say ‘no’ to the Government. This deliberate refusal to cooperate is like the necessary weeding process that a cultivator has to resort before he sows. Weeding is as necessary to agriculture as sowing. Indeed, even whilst the crops are growing, the weeding fork, as every husbandman knows, is an instrument almost of daily use. The nation’s Non-cooperation is an invitation to the Government to co-operate with it on its own terms as is every nation’s right and every good government’s duty. Non-cooperation is the nation’s notice that it is no longer satisfied to be in tutelage. The nation had taken to the harmless (for it), natural and religious doctrine of Non-cooperation in the place of the unnatural and irreligious doctrine of violence. And if India is ever to attain the swaraj of the Poet’s dream, she will do so only by Non-violent Non-cooperation. Let him deliver his message of peace to the world, and feel confident that India, through her Non- cooperation, if she remains true to her pledge, will have exemplified his message. Non-cooperation is intended to give the very meaning to patriotism that the Poet is yearning after. An India prostrate at the feet of Europe can give no hope to humanity. An India awakened and free has a message of peace and goodwill to a groaning world. Non-cooperation is designed to supply her with a platform from which she will preach the message.

…if India is ever to attain the swaraj of the Poet’s dream, she will do so only by Non-violent Non-cooperation. Let him deliver his message of peace to the world, and feel confident that India, through her Non- cooperation, if she remains true to her pledge, will have exemplified his message. Non-cooperation is intended to give the very meaning to patriotism that the Poet is yearning after. An India prostrate at the feet of Europe can give no hope to humanity. An India awakened and free has a message of peace and goodwill to a groaning world. Non-cooperation is designed to supply her with a platform from which she will preach the message.

(This long rejoinder from Tagore to Gandhi originally appeared in Pravasee in Bengali and later in Modern Review in English. The original is reproduced in Volume XXIV of the Collected Works of Rabindranath Tagore)

Parasites have to pay for their readymade victuals by losing the power, of assimilating food in natural form. In the history of man, this same sin of laziness has always entailed degeneracy. Man becomes parasitical, not only when he fattens on others’ toil, but also when he becomes rooted to a particular set of outside conditions and allows himself helplessly to drift along the stream of things as they are; for the outside is alien to the inner self, and if the former be made indispensable by sheer habit, man acquires parasitical characteristics, and becomes unable to perform his true function of converting the impossible into the possible.

In this sense all the lower animals are parasites. They are carried along by their environment; they live or die by natural selection; they progress or retrogress as nature may dictate. Their mind has lost the power of growth. The bees, for millions of years, have been unable to get beyond the pattern of their hive. For that reason, the form of their cell has attained certain perfection, but their mentality is confined to the age-long habits of their hive-life and cannot soar out of its limitations. Nature has developed a cautious timidity in the case of her lower types of life; she keeps them tied to her apron strings and has stunted their minds, lest they should stray into dangerous experiments.

But Providence displayed a sudden accession of creative courage when it came to man; for his inner nature has not been tied down, though outwardly the poor human creature has been left naked, weak and defenceless. In spite of these disabilities, man in the joy of his inward freedom has stood up and declared: “I shall achieve the impossible”. That is to say, he has consistently refused to submit to the rule of things as they always have been, but is determined to bring about happenings that have never been before. So when, in the beginning of his history, man’s lot was thrown in with monstrous creatures, tusked and taloned, he did not, like the deer, simply take refuge in flight, nor, like the tortoise, take refuge in biding, but set to work with flints to make even more efficient weapons. These, moreover, being the creation of his own inner faculties, were not dependent on natural selection, as were those of the other animals, for their developments. And so man’s instruments progressed from flint to steel. This shows that man’s mind has never been helplessly attached to his environment. What came to his hand was brought under his thumb. Not content with the flint on the surface, he delved for the iron beneath. Not satisfied with the easier process of chipping flints, he proceeded to melt iron ore and hammer it into shape. That which resisted more stubbornly was converted into a better ally. Man’s inner nature not only finds success in its activity, but there it also has its joy. He insists on penetrating further and further into the depths, from the obvious to the hidden, from the easy to the difficult, from parasitism to self-determination, from the slavery of his passions to the mastery of himself. That is how he has won.

But if any section of mankind should say, “The flint was the weapon of our revered forefathers; by departing from it we destroy the spirit of the race”, then they may succeed in preserving what they call their race, but they strike at the root of the glorious tradition of humanity which was theirs also. And we find that those, who have steadfastly stuck to their flints, may indeed have kept safe their pristine purity to their own satisfaction, but they have been out casted by the rest of mankind, and so have to pass their lives slinking away in jungle and cave. They are, as I say, reduced to a parasitic dependence on outside nature, driven along blindfold by the force of things as they are. They have not achieved swaraj in their inner nature, and so are deprived of swaraj in the outside world as well. They have ceased to be even aware, that it is man’s true function to make the impossible into the possible by dint of his own powers; that it is not for him to be confined merely to what has happened before; that he must progress towards what ought to be by rousing all his inner powers by means of the force of his soul.

Thirty years ago I used to edit the Sadhana magazine and there I tried to say this same thing. Then English-educated India was frightfully busy begging for its rights. And I repeatedly endeavoured to impress on my countrymen, that man is not under any necessity to beg for rights from others, but must create them for himself; because man lives mainly by his inner nature, and there he is the master. By dependence on acquisition from the outside, man’s inner nature suffers loss. And it was my contention, that man is not so hard oppressed by being deprived of his outward rights as he is by the constant bearing of the burden of prayers and petitions.

Then when the Bangadarshan magazine came into my hands, Bengal was beside herself at the sound of the sharpening of the knife for her partition. The boycott of Manchester, which was the outcome of her distress, had raised the profits of the Bombay mill-owners to a super-foreign degree. And I had then to say: “This will not do, either; for it is also of the outside. Your main motive is hatred of the foreigner, not love of country.” It was then really necessary for our countrymen to be made conscious of the distinction, that the Englishman’s presence is an external accident, mere maya but that the presence of our country is an internal fact which is also an eternal truth. Maya looms with an exaggerated importance, only when we fix our attention exclusively upon it, by reason of some infatuation—be it of love or of hate. Whether in our passion we rush to embrace it, or attack it; whether we yearn for it, or spurn it; it equally fills the whole field of our blood-shot vision.

Maya is like the darkness. No steed, however swift, can carry us beyond it; no amount of water can wash it away. Truth is like a lamp; even as it is lit, maya vanishes. Our shastras tell us that Truth, even when it is small, can rescue us from the terror which is great. Fear is the atheism of the heart. It cannot be overcome from the side of negation. If one of its heads be struck off, it breeds like the monster of the fable, a hundred others. Truth is positive; it is the affirmation of the soul. If even a little of it be roused, it attacks negation at the very heart and overpowers it wholly.

Maya is like the darkness. No steed, however swift, can carry us beyond it; no amount of water can wash it away. Truth is like a lamp; even as it is lit, maya vanishes. Our shastras tell us that Truth, even when it is small, can rescue us from the terror which is great. Fear is the atheism of the heart. It cannot be overcome from the side of negation. If one of its heads be struck off, it breeds like the monster of the fable, a hundred others. Truth is positive; it is the affirmation of the soul. If even a little of it be roused, it attacks negation at the very heart and overpowers it wholly.

Alien government in India is a veritable chameleon. Today it comes in the guise of the Englishman; tomorrow perhaps as some other foreigner; the next day, without abating a jot of its virulence, it may take the shape of our own countrymen. However determinedly we may try to hunt this monster of foreign dependence with outside lethal weapons, it will always elude our pursuit by changing its skin, or its colour. But if we can gain within us the truth called our country, all outward maya will vanish of itself. The declaration of faith that my country is there, to be realised, has to be attained by each one of us. The idea that our country is ours, merely because we have been born in it, can only be held by those who are fastened, in a parasitic existence, upon the outside world. But the true nature of man is his inner nature, with its inherent powers. Therefore, that only can be a man’s true country, which he can help to create by his wisdom and will, his love and his actions. So in 1905, I called upon my countrymen to create their country by putting forth their own powers from within. For the act of creation itself is the realization of truth.

The Creator gains Himself in His universe. To gain one’s own country means to realize one’s own soul more fully expanded within it. This can only be done when we are engaged in building it up with our service, our ideas and our activities. Man’s country being the creation of his own inner nature, when his soul thus expands within it, it is more truly expressed, more fully realised. In my paper called Swadeshi Samaj, written in 1905, I discussed at length the ways and means by which we could make the country of our birth more fully our own. Whatever may have been the shortcomings of my words then uttered, I did not fail to lay emphasis on the truth, that we must win our country, not from some foreigner, but from our own inertia, our own indifference. Whatever be the nature of the boons we may be seeking for our country at the door it only makes our inertia more densely inert. Any public benefit done by the alien Government goes to their credit not to ours. So whatever outside advantage such public benefit might mean for us, our country will only get more and more completely lost to us thereby. That is to say, we shall have to pay out in soul value for what we purchase as material advantage. The Rishi has said: “The son is dear, not because we desire a son, but because we desire to realize our own soul in him.” It is the same with our country. It is dear to us, because it is the expression of our own soul. When we realize this, it will become impossible for us to allow our service of our country to wait on the pleasure of others.

These truths, which I then tried to press on my countrymen, were not particularly new, nor was there anything therein which need have grated on their ears; but, whether anyone else remembers it or not, I at least am not likely to forget the storm of indignation which I roused. I am not merely referring to the hooligans of journalism whom it pays to be scurrilous. But even men of credit and courtesy were unable to speak of me in restrained language.

There were two root causes of this. One was anger, the second was greed.

Giving free vent to angry feelings is a species of self-indulgence. In those days there was practically nothing to stand in the way of the spirit of destructive revel, which spread all over the country. We went about picketing, burning, placing thorns in the path of those whose way was not ours, acknowledging to restraints in language or behavior, – all in the frenzy of our wrath. Shortly after it was all over, a Japanese friend asked me: “How is it you people cannot carry on your work with calm and deep determination? This wasting of energy can hardly be of assistance to your object.” I had no help but to reply: “When we have the gaining of the object clearly before our minds, we can be restrained, and concentrate our energies to serve it; but when it is a case of venting our anger, our excitement rises and rises till it drowns the object and then we are spend-thrift to the point of bankruptcy.” However that may be, there were my countrymen encountering, for the time being, no check to the overflow of their outraged feelings. It was like a strange dream. Everything seemed possible. Then all of a sudden it was my misfortune to appear on the scene with my doubts and my attempts to divert the current into the path of self-determination. My only success was in diverting their wrath on to my own devoted head.

“When we have the gaining of the object clearly before our minds, we can be restrained, and concentrate our energies to serve it; but when it is a case of venting our anger, our excitement rises and rises till it drowns the object and then we are spend-thrift to the point of bankruptcy.” However that may be, there were my countrymen encountering, for the time being, no check to the overflow of their outraged feelings. It was like a strange dream. Everything seemed possible. Then all of a sudden it was my misfortune to appear on the scene with my doubts and my attempts to divert the current into the path of self-determination. My only success was in diverting their wrath on to my own devoted head.

Then there was our greed. In history, all people have won valuable things by pursuing difficult paths. We had hit upon the device of getting them cheap, not even through the painful indignity of supplication with folded hands, but by proudly conducting our beggary in threatening tones. The country was in ecstasy at the ingenuity of the trick. It felt like being at a reduced price sale. Everything worth having in the political market was ticketed at half-price. Shabby-genteel mentality is so taken up with low prices that it has no attention to spare for quality and feels inclined to attack anybody who has the hardihood to express doubts in that regard. It is like the man of worldly piety who believes that the judicious expenditure of coin can secure, by favour of the priest, a direct passage to heaven. The dare devil who ventures to suggest that not heaven but dreamland is likely to be his destination must beware of a violent end.

Anyhow, it was the outside maya which was our dream and our ideal in those days. It was a favourite phrase of one of the leaders of the time that we must keep one hand at the feet and the other at the throat of the Englishman, that is to say, with no hand left free for the country! We have since perhaps got rid of this ambiguous attitude. Now we have one party that has both hands raised to the foreigner’s throat, and another party which has both hands down at his feet; but whichever attitude it may be, these methods still appertain to the outside maya. Our unfortunate minds keep revolving round and round the British Government, now to the left, now to the right; our affirmations and denials alike are concerned with the foreigners.

In those days, the stimulus from every side was directed towards the heart of Bengal. But emotion by itself, like fire only consumes its fuel and reduces it to ashes; it has no creative power. The intellect of man must busy itself, with patience, with skill, with foresight, in using this fire to melt that which is hard and difficult into the object of its desire. We neglected to rouse our intellectual forces, and so were unable to make use of this surging emotion of ours to create any organisation of permanent value. The reason of our failure, therefore, was not in anything outside, but rather within us. For a long time past we have been in the habit, in our life and endeavour, of setting apart one place for our emotions and another for our practices. Our intellect has all the time remained dormant, because we have not dared to allow it scope. That is why, when we have to rouse ourselves to action, it is our emotion which has to be requisitioned, and our intellect has to be kept from interfering by the hypnotism of some magical formula,—that is to say we hasten to create a situation absolutely inimical to the free play of our intellect.

The loss which is incurred by this continual deadening of our mind cannot be made good by any other contrivance. In our desperate attempts to do so we have to invoke the magic of maya and our impotence jumps for joy at the prospect of getting hold of Alladin’s lamp. Of course everyone has to admit that there is nothing to beat Alladin’s lamp, its only inconvenience being that it beats one to get hold of. The unfortunate part of it is that the person, whose greed is great, but whose powers are feeble, and who has lost all confidence in his own intellect, simply will not allow himself, to dwell on the difficulties of bespeaking the services of some genie of the lamp. He can only be brought to exert himself at all by holding out the speedy prospect of getting at the wonderful lamp. If anyone attempts to point out the futility of his hopes, he fills the air with wailing and imprecation, as at a robber making away with his all.

In the heat of the enthusiasm of the partition days, a band of youths attempted to bring about the millennium through political revolution. Their offer of themselves as the first sacrifice to the fire which they had lighted makes not only their own country, but other countries as well, bare the head to them in reverence. Their physical failure shines forth as the effulgence of spiritual glory. In the midst of the supreme travail, they realised at length that the way of bloody revolution is not the true way; that where there is no politics, a political revolution is like taking a short cut to nothing; that the wrong way may appear shorter, but it does not reach the goal, and only grievously hurts the feet. The refusal to pay the full price for a thing leads to the loss of the price without the gain of the thing. These impetuous youths offered their lives as the price of their country’s deliverance; to them it meant the loss of their all but alas! the price offered on behalf of the country was insufficient. I feel sure that those of them who still survive must have realised by now, that the country must be the creation of all its people, not of one section alone. It must be the expression of all their forces of heart, mind and will.

This creation can only be the fruit of that yoga, which gives outward form to the inner faculties. Mere political or economical yoga is not enough; for that all the human powers must unite.

When we turn our gaze upon the history of other countries, the political steed comes prominently into view; on it seems to depend wholly the progress of the carriage. We forget that the carriage also must be in a fit condition to move; its wheels must be in agreement with one another and its parts well fitted together; with which not only have fire and hammer and chisel been busy but much thought and skill and energy have also been spent in the process. We have seen some countries which are externally free and independent; when however, the political carriage is in motion, the noise which it makes arouses the whole neighbourhood from slumber and the jolting produces aches and pains in the limbs of the helpless passengers. It comes to pieces in the middle of the road, and it takes the whole day to put it together again with the help of ropes and strings. Yet however loose the screws and however crooked the wheels, still it is a vehicle of some sort after all. But for such a thing as is our country a mere collection of jointed logs, that not only have no wholeness amongst themselves, but are contrary to one another for this to be dragged along a few paces by the temporary pull of some common greed or anger, can never be called by the name of political progress. Therefore, is it not, in our case, wiser to keep for the moment our horse in the stable and begin to manufacture a real carriage?

From the writings of the young men, who have come back out of the valley of the shadow of death, I feel sure some such thoughts must have occurred to them. And so they must be realising the necessity of the practice of yoga as of primary importance;—that from which is the union in a common endeavour of all the human faculties. This cannot be attained by any outside blind obedience, but only by the realisation of self in the light of intellect. That which fails to illumine the intellect, and only keeps it in the obsession of some delusion, is its greatest obstacle.

The call to make the country our own by dint of our own creative power, is a great call. It is not merely inducing the people to take up some external mechanical exercise; for man’s life is not in making cells of uniform pattern like the bee, nor in incessant weaving of webs like the spider; his greatest powers are within, and on these are his chief reliance. If by offering some allurement we can induce man to cease from thinking, so that he may go on and on with some mechanical piece of work, this will only result in prolonging the sway of maya, under which our country has all along been languishing. So far, we have been content with surrendering our greatest right—the right to reason and to judge for ourselves—to the blind forces of shastric injunctions and social conventions. We have refused to cross the seas, because Manu has told us not to do so. We refuse to eat with the Mussalman, because prescribed usage is against it. In other words, we have systematically pursued a course of blind routine and habit, in which the mind of man has no place. We have thus been reduced to the helpless condition of the master who is altogether dependent on his servant. The real master, as I have said, is the internal man; and he gets into endless troubles, when he becomes his own servant’s slave—a mere automaton, manufactured in the factory of servitude. He can then only rescue himself from one master by surrendering himself. Similarly, he who glorifies inertia by attributing to it a fanciful purity, becomes, like it, dependent on outside impulses, both for rest and motion. The inertness of mind, which is the basis of all slavery, cannot be got rid of by a docile, submission to being hoodwinked, nor by going through the motions of a wound-up mechanical doll.

So far, we have been content with surrendering our greatest right—the right to reason and to judge for ourselves—to the blind forces of shastric injunctions and social conventions. We have refused to cross the seas, because Manu has told us not to do so. We refuse to eat with the Mussalman, because prescribed usage is against it. In other words, we have systematically pursued a course of blind routine and habit, in which the mind of man has no place. We have thus been reduced to the helpless condition of the master who is altogether dependent on his servant. The real master, as I have said, is the internal man; and he gets into endless troubles, when he becomes his own servant’s slave—a mere automaton, manufactured in the factory of servitude. He can then only rescue himself from one master by surrendering himself.

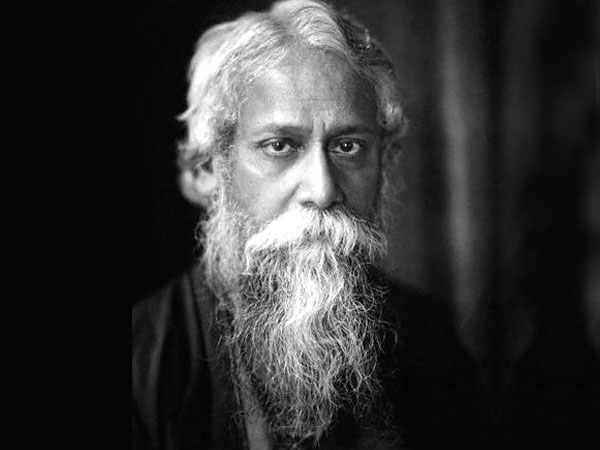

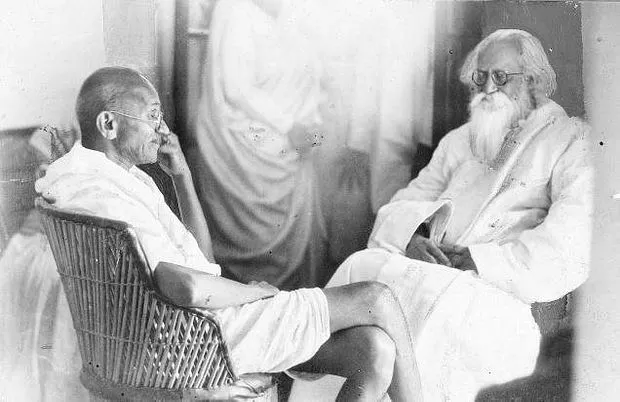

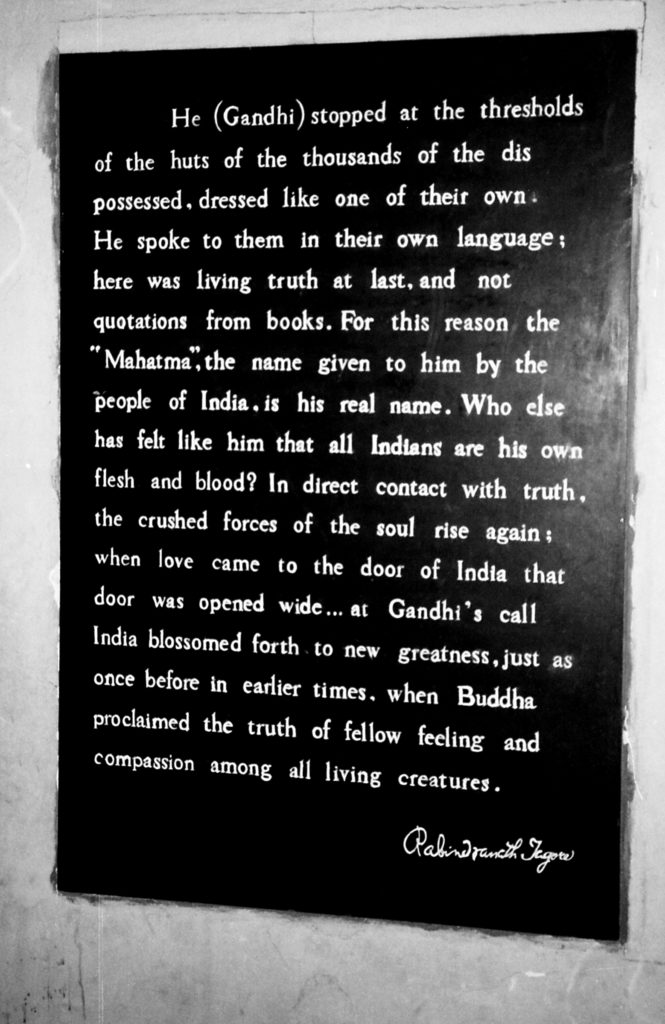

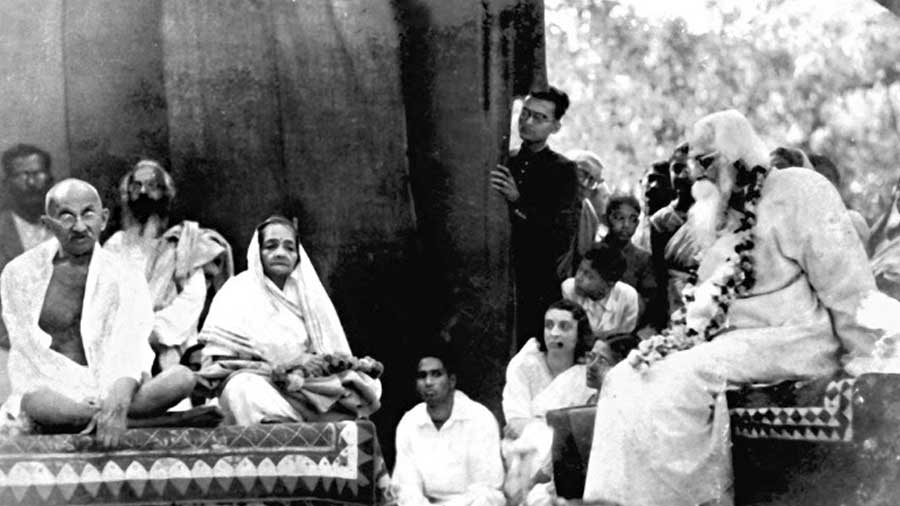

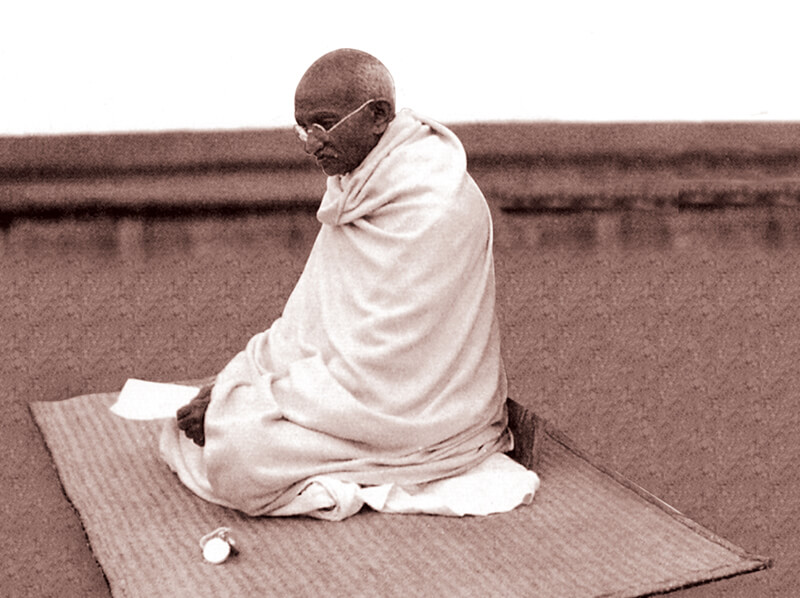

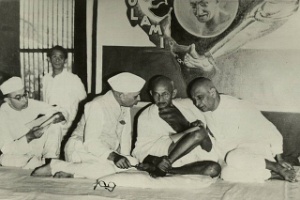

The movement, which has now succeeded the swadeshi agitation, is ever so much greater and has moreover extended its influence all over India. Previously, the vision of our political leaders had never reached beyond the English-knowing classes, because the country meant for them only that bookish aspect of it which is to be found in the pages of the Englishman’s history. Such a country was merely a mirage born of vapourings in the English language, in which litted about thin shades of Burke and Gladstone, Mazzini and Garibaldi. Nothing resembling self-sacrifice or true feeling for their countrymen was visible. At this juncture, Mahatma Gandhi came and stood at the cottage door of the destitute millions, clad as one of themselves, and talking to them in their own language. Here was the truth at last, not a mere quotation out of a book. So the name of Mahatma, which was given to him, is his true name. Who else has felt so many men of India to be of his own flesh and blood? At the touch of Truth the pent-up forces of the soul are set free. As soon as true love stood at India’s door, it flew open; all hesitation and holding back vanished. Truth awakened truth.

Stratagem in politics is a barren policy—this was a lesson of which we were sorely in need. All honour to the Mahatma, who made visible to us the power of Truth. But reliance on tactics is so ingrained in the cowardly and the weak, that in order to eradicate it, the very skin must be sloughed off. Even today, our worldly-wise men cannot get rid of the idea of utilising the Mahatma at a secret and more ingenious move in their political gamble. With their minds corroded by untruth, they cannot understand what an important thing it is that the Mahatma’s supreme love should have drawn forth the country’s love. The thing that has happened is nothing less than the birth of freedom. It is the gain by the country of itself. In it there is no room for any thought, as to where the Englishman is, or is not. This love is self- expression. It is pure affirmation. It does not argue with negation: it has no need for argument.

Some notes of the music of this wonderful awakening of India by love, floated over to me across the seas. It was a great joy to me to think that the call of this festivity of awakening would come to each one of us; and that the true shakti of India’s spirit, in all its multifarious variety, would at last find expression. This thought came to me because I have always believed that in such a way India would find its freedom. When Lord Buddha voiced forth the truth of compassion for all living creatures, the manhood of India was roused and poured itself forth in science and art and wealth of every kind. True in the matter of political unification the repeated attempts that were then made as often failed; nevertheless India’s mind had awakened into freedom from its submergence in sleep, and its overwhelming force would brook no confinement within the petty limits of country. It overflowed across ocean and desert, scattering its wealth of the spirit over every land that it touched. No commercial or military exploiter, to-day has ever been able to do anything like it. Whatever land these exploiters have touched has been agonised with sorrow and insult, and the fair face of the world has been scarred and disfigured. Why? Because not greed but love is true. When love gives freedom it does so at the very centre of our life. When greed seeks unfettered power, it is forcefully impatient. We saw this during the partition agitation. We then compelled the poor to make sacrifices, not always out of the inwardness of love, but often by outward pressure. That was because greed is always seeking for a particular result within a definite time. But the fruit which love seeks is not of today or tomorrow, or for a time only: it is sufficient unto itself.

No commercial or military exploiter, to-day has ever been able to do anything like it. Whatever land these exploiters have touched has been agonised with sorrow and insult, and the fair face of the world has been scarred and disfigured. Why? Because not greed but love is true. When love gives freedom it does so at the very centre of our life. When greed seeks unfettered power, it is forcefully impatient. We saw this during the partition agitation. We then compelled the poor to make sacrifices, not always out of the inwardness of love, but often by outward pressure. That was because greed is always seeking for a particular result within a definite time. But the fruit which love seeks is not of today or tomorrow, or for a time only: it is sufficient unto itself.

So, in the expectation of breathing the buoyant breezes of this new found freedom, I came home rejoicing. But what I found in Calcutta when I arrived depressed me. An oppressive atmosphere seemed to burden the land. Some outside compulsion seemed to be urging one and all to talk the same strain, to work at the same mill. When I wanted to inquire, to discuss, my well- wishers clapped their hands over my lips, saying: “Not now, not now”. Today, in the atmosphere of the country, there is a spirit of persecution, which is not that of armed force, but something still more alarming, because it is invisible. I found, further, that those who had their doubts as to the present activities, if they happened to whisper them out, however cautiously, however guardedly, felt some admonishing hand clutching them within. There was a newspaper which one day had the temerity to disapprove, in a feeble way, of the burning of cloth. The very next day, the editor was shaken out of his balance by the agitation of his readers. How long would it take for the fire which was burning cloth to reduce his paper to ashes? The sight that met my eye was, on the one hand people immensely busy; on the other, intensely afraid. What I heard on every side was, that reason, and culture as well, must be closured. It was only necessary to cling to an unquestioning obedience. Obedience to whom? To some mantra, some unreasoned creed!

And why this obedience? Here again comes that same greed, our spiritual enemy. There dangles before the country the bait of getting a thing of inestimable value dirt cheap and in double-quick time. It is like the faqir with his goldmaking trick. With such a lure men cast so readily to the winds their independent judgement and wax so mightly wroth with those who will not do likewise. So easy is to overpower, in the name of outside freedom the inner freedom of man. The most deplorable part of it is that so many do not even honestly believe in the hope that they swear by. “It will serve to make our countrymen do what is necessary”—say they. Evidently, according to them, the India which once declared: “In truth is Victory, not in untruth”—that India would not have been fit for Swaraj.

Another mischief is that the gain, with the promise of which obedience is claimed, is indicated by name, but is not defined, just as when fear is vague it becomes all the more strong, so the vagueness of the lure makes it all the more tempting; inasmuch as ample room is left for each one’s imagination to shape it to his taste. Moreover there is no driving it into a corner because it can always shift from one shelter to another. In short, the object of the temptation has been magnified through its indefiniteness while the time and method of its attainment have been made too narrowly definite. When the reason of man has been overcome in this way, he easily consents to give up all legitimate questions and blindly follows the path of obedience. But can we really afford to forget so easily that delusion is at the root of all slavery —that all freedom means freedom from maya? What if the bulk of our people have unquestioningly accepted the creed, that by means of sundry practices swaraj will come to them on a particular date in the near future and are also ready to use their clubs to put down all further argument,—that is to say, they have surrendered the freedom of their own minds and are prepared to deprive other minds of their freedom likewise,—is not this by itself a reason for profound misgiving? We were seeking the exerciser to drive out this very ghost; but if the ghost itself comes in the guise of exerciser then the danger is only heightened.

The Mahatma has won the heart of India with his love; for that we have all acknowledged his sovereignty. He has given us a vision of the shakti of Truth; for that our gratitude to him is unbounded. We read about Truth in books: we talk about it: but it is indeed a red-letter day, when we see it face to face. Rare is the moment, in many a long year, when such good fortune happens. We can make and break Congresses every other day. It is at any time possible for us to stump the country preaching politics in English. But the golden rod, which can awaken our country in Truth and Love is not a thing which can be manufactured by the nearest goldsmith. To the weilder of that rod our profound salutation! But if having seen Truth, our belief in it is not confirmed, what is the good of it all? Our mind must acknowledge the Truth of the intellect, just as our heart does the Truth of love. No Congress or other outside institution succeeded in touching the heart of India. It was roused only by the touch of love. Having had such a clear vision of this wonderful power of Truth, are we to cease to believe in it, just where the attainment of Swaraj is concerned? Has the Truth, which was needed in the process of awakenment, to be got rid of in the process of achievement?

Let me give an illustration. I am in search of a vina player. I have tried East and I have tried West, but have not found the man of my quest. They are all experts, they can make the strings resound to a degree, they command high prices, but for all their wonderful execution they can strike no chord in my heart. At last I come across one whose very first notes melt away the sense of oppression within. In him is the fire of the shakti of joy which can light up all other hearts by its touch. His appeal to me is instant and I hail him as Master. I then want a vina made. For this, of course are required all kinds of material and a different kind of science. If, finding me to be lacking in the means my master should be moved to pity and say: “Never mind, my son do not go to the expense in workmanship and time which a vina will require. Take rather this simple string tightened across a piece of wood and practise on it. In a short time you will find it to be as good as a vina.” Would that do? I am afraid not. It would, in fact, be a mistaken kindness for the master thus to take pity on my circumstances. Far better if he were to tell me plainly that such things cannot be had cheaply. It is he who should teach me that merely one string will not serve for a true vina, that the materials required are many and various; that the lines of its moulding must be shapely and precise; that if there be anything faulty, it will fail to make good music, so that all laws of science and technique of art must be rigorously and intelligently followed. In short the true function of the master player should be to evoke a response from the depths of our heart, so that we may gain the strength to wait and work till the true end is achieved.