(Quotes in this introduction, where not attributed, are from Romila Thapar’s essay Voices of Dissent.)

‘Dissent’ is a word that hangs loosely on the lips of many Indians today. Not dissent itself, necessarily, but its meaning in today’s context: What constitutes the right to dissent? Is dissent necessary? If so, how much?

We hear much, for instance, of dissent being the cornerstone of democracy. This, unwittingly, sometimes promotes the mistaken view that the idea of the importance of dissent is an import from the western enlightenment.

Not so. Dissent – defined by Romila Thapar in the first line of her remarkably important essay Voices of Dissent as “in essence, the disagreement that a person or persons may have with others, or, more publicly, with some of the institutions that govern their pattern of life” – has been a pre-requirement for any societal progress. “Earlier, only the powerful had this right, but today it extends—in theory at least—to all citizens,” writes Thapar in the introductory section of the essay. “In earlier times the right was often argued over but did not always become a public issue as it can in our times.”

How then do we recognise this dissent in earlier times? Writes Thapar: “Those dissenting do not always proclaim themselves as dissenters; sometimes, they may not even be fully aware of the degree to which they are dissenting. One of the more obvious ways of recognizing dissent is to mark the presence of ‘the Other’ in society.”

To explain what she means by ‘the Other’, Thapar first outlines an ‘established’ society or ‘the Self’ (borrowing, as she says, from Edward Said), then writes: “It is a person or a group of people who declare themselves to be or are recognized as different because they question some of the views of the Self.” Who determines this? “Those in authority generally see themselves as the established Self, and they are the ones who set up the dichotomous identity of the Self vis-a-vis the Other… Generally the one who questions the Self.” Further: “People from different geographies and cultures are not the only ones thought of as the Other. More often… the Other emerges from within the same society. Since societies are stratified, socially and culturally, there is divergence—divergence caused by environment and location, economy and technology, systems of kinship and inheritance, concepts of belief and worship, and, in some cases, physical differences.”

The idea behind Thapar’s essay is to “try and understand why a certain kind of Other received such a ready and substantial response from the public, both in the past and in modern times.” In doing so, she provides us a lens with which to view dissent and dialogue in Indian history as a continuum. This stands in stark contrast to those who, in her words, “visualize the Indian past as free of blemishes and therefore not requiring dissenting opinions” (the idea of an unimpeachable and lost ‘golden age’) as well as those who wish to portray dissent as something that burst into Indian consciousness as a consequence of colonization and liberal ideas from abroad (the idea of ‘the gift of the West’).

To illustrate the Indian subcontinent’s longstanding and healthy history of dissent, Thapar chooses three examples from pre-modern history: the concept of a Brahmana who is the son of a Dasi from Vedic times— the second millennium BC; the emergence of groups that were jointly called Shramanas or Nastika; and the views of the Bhakti sants and Sufi pirs of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries AD. “My choice has been with reference to religion in a broad sense,” Thapar writes. “Because religion when used as ideology motivates supporters to also follow a social pattern. The interface between religion and society illumines both.”

We have republished here below the section of the essay pertaining to the second example, titled ‘The Presence of the Shramanas’. The Shramanas – comprising the Jainas, Buddhists and Ajivikas (some would include the Charvakas / Lokayatas, though Thapar doesn’t) – were an Other “opposed in varying degrees to Vedic Brahmanism. They questioned the belief in deities, in the Vedas being divinely revealed, in the efficacy of the yajna / ritual of sacrifice, and in the existence of the individual soul or atman.” The word might loosely translate to mean a seeker who exerts oneself for a higher purpose. Thapar asserts that “The Charvakas were not Shramanas” but “there developed a tendency for Brahmanical texts to list the non-Brahmanical schools altogether in one list and describe them all as nastika / non-believers.”

Let’s consider the Charvakas first, “neglected because of our obsession with the idea that India has only respected non-materialist philosophies in the past”. They didn’t leave behind any significant text on their philosophy and find hostile mentions in Brahmanical and Buddhist literature, yet, evidence such as a chapter in Madhvacharya’s Sarva-darshana-samgraha and records from Akbar’s time mentioning his inviting them to his court suggest their influence “through the centuries to medieval times”. “They are likely to have been in dialogue with the other streams,” writes Thapar, “Else they would have faded out before the fourteenth century.”

Next, the Shramanic religions, whose teachings “revolved round each of their historical founders”. The Buddhists, for example, “accepted the Buddha, the dhamma / dharma and the Sangha as the pillars of their teaching.” They had fewer rituals and few demarcated places of worship (eg. chaityas / halls of worship and stupas / relic mounds) focusing instead on discussion or texts. The question of ahimsa / nonviolence was central to the Shramanic teachings (not so in the Brahmanical texts). Shramanas were also open to ‘lower’ castes, “who could become lay followers or monks”. Thapar puts the period “between the Mauryas and the Guptas” as one where there is a presence of Buddhist stupas and absence of temples, “a situation that was slowly reversed in the subsequent post-Gupta period”. “Possibly, it could be said,” she writes. “That it was a period when the Shramanas were the more established Selves as it were, and the emerging Puranic Hinduism was a competitor— a position that was reversed in the post-Gupta period.”

In the post-Gupta period, Thapar enquires into not only the shifting of patronage to Brahmanism (“unsettling the Shramanas”) but also the preponderance of “a form of Hinduism that might be better referred to as Puranic Hinduism”: “the worship of various manifestations of Vaishnavism and Shaivism to begin with and [which] later included the Shakta-Shakti and other cults.” Local deities were inducted into the Puranic pantheon, with the ritual specialists (with regard to these deities) comprising separate caste categories or being “drawn into the brahmana caste”.

Puranic Hinduism was different from Vedic Brahmanism in many ways, though it invokes the latter: the primary texts were the Puranas, available in a more widely spoken version of Sanskrit than the Vedas and “in later centuries even more in local languages”; Unlike the Vedas, which had restricted reading and recitation, the Puranas were meant for more popular audiences; “unlike the major Vedic sacrificial rituals that were not associated with the worship of idols and could be performed wherever thought suitable, and whose locations were disbanded at the conclusion of the ritual, Puranic Hinduism now began building permanent places of worship… temples housing images of deities with an increasing focus on their worship”. Thapar cites a discussion in the dharma-shastras “on which brahmana is to be given priority—the one who is a specialist in the Vedas or the temple priest”.

Buddhism “faded from being foremost among the Shramana religions” after being “active in a few pockets and more so in eastern India”. Thapar puts down its decline further to “a decline in commerce” as well as “the diversion of royal donations elsewhere”. She debunks the myth that Islam was responsible for its decline, citing Buddhist monk Xuanzang, since “Buddhism had ceased to be pre-eminent even before the coming of Islam to North India”. However, it acquired a “spectacular following” in most other parts of Asia. The Jainas survived by “consolidating their patronage and rooting themselves in specific areas such as Karnataka and Western India, supported substantially by the wealthy mercantile community and occasionally by royalty”. Writes Thapar: “Their monasteries became centres of scholarship focusing on their own teaching and thus forming a kind of counterpart to the mathas of the brahmanas. Many had a proficiency in accounting and finance that linked them to the commercial activities of those times and to the lives of trading communities. Possibly some concession was made here or there in ritual and worship, as in the spectacular temples they built, that indicated their well-being.”

Most crucially Thapar, in this section of her essay, delves into:

– the hostility and rivalry (including the emergence of ‘heresy’ in various texts, such as the Puranas to refer to Buddhists and Jainas) between the Brahmanical and Shramanic religions;

– Divisions within these religions into sects/schools (Shaiva, Vaishnava and Shakta; Mahayana and Hinayana; Digambara and Shvetambara);

– “institutions that religious groups built to support their activities and through which conformity or dissent was expressed”, the personality of the ‘renouncer’ and patronage links between not just royalty but also other wealthy patrons and these institutions, and;

– finally, the extension of the influence of these institutions into social and political matters.

Thapar’s complex exploration of the above is best read, by those interested, in the text below as summing it up here would make this introduction even longer than it presently is.

“Curiously,” writes Thapar, “Despite all these changes and challenges to existing norms, there seems to have been some hesitation in dissent turning into revolt. Dissent was perhaps a way of containing it.” Caste rules were reformulated by those who could get away with it, new deities and rituals were incorporated, new teaching allowed for in some places. Thapar cites the “acceptance of interpolations into texts such as the Mahabharata, Ramayana and Gita” through which the texts were “living with the times”.

Thapar writes that “the awareness of the possibility of revolt was known but discouraged.” For instance: “The Mahabharata allows the assassination of oppressive kings but only by those capable of making such a judgement such as the brahmanas.”

Buddhist sources, however, are more democratic, possibly “an outcome of the Buddhist view on the origin of the state, repeated in the Mahabharata”: “It is narrated that when the pristine utopia of human society began to decline with the introduction of kinship rules and ownership of property determining social-behaviour, the people affected by this change gathered and elected one from among themselves to make laws and to rule over them in accordance with the laws.” A kind of “social contract”.

Thapar ends the section by writing: “References to peasants threatening to revolt appear to be made more frequently in the second millennium AD, but these may just have been rhetorical. Actual disturbances are few. Similarly, when some urban artisans also objected to the amount of taxes and rents they had to pay, an agreement was negotiated.”

Let me now turn to my second and rather different example: an existing culture gives rise to an alternative Other from within itself. The Other here was not regarded as being of an alien culture but, evolving out of a similar culture, was nevertheless dissenting from the codes of dominant groups. I am taking you now into the early ADs, to the emergence of groups that were a different Other and were jointly called the Shramanas—these were the Jainas, Buddhists and Ajivikas. Some would include the Charvakas / Lokayatas as well, although their thinking was very different.

The teachings of the Shramanas revolved round each of their historical founders. The Buddhists, for example, accepted the Buddha, the dhamma / dharma and the Sangha as the pillars of their teaching. They had fewer elaborate public rituals and used discussion or texts when stating their principles. They had a few demarcated places of worship, the chaityas and stupas. The latter held the relics of the venerated dead, contrary to Vedic practice.

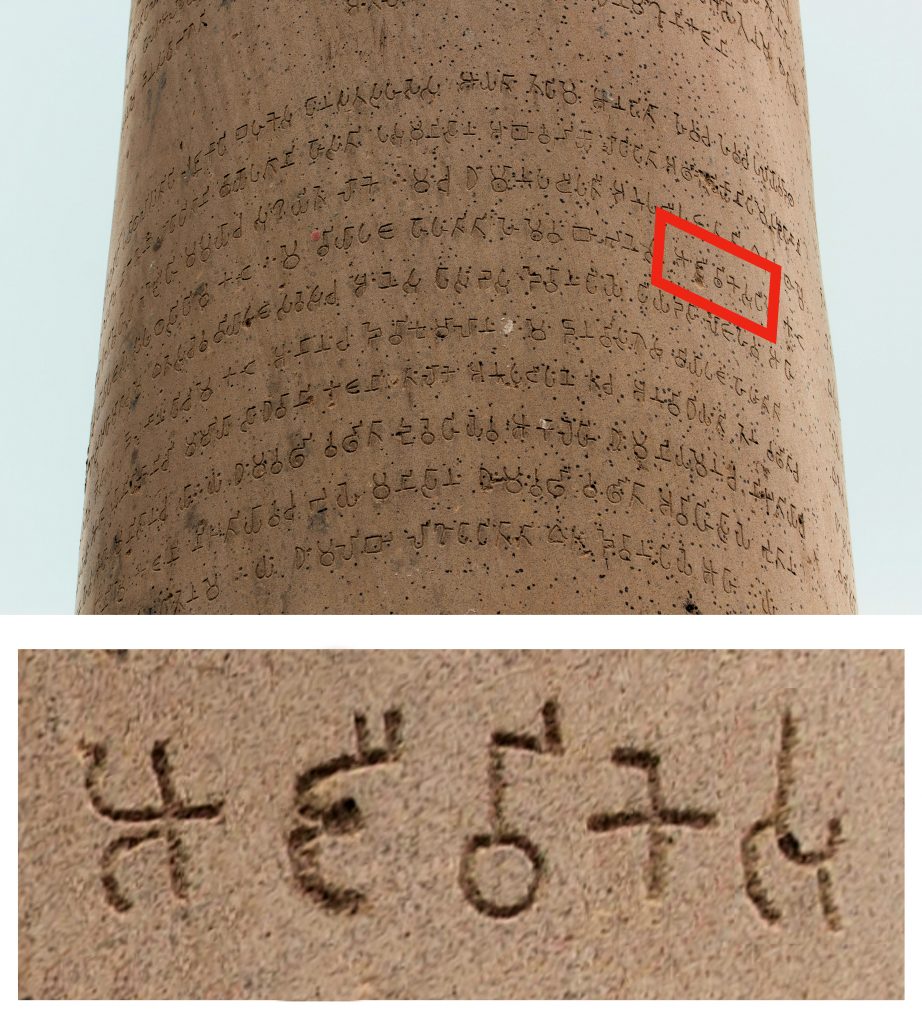

Mention of the Ajivikas on the Ashoka pillar, Feroz Shah Kotla, Delhi.

The question of ahimsa / nonviolence was central to the teaching of the Buddhists and Jainas. This was not so in the texts endorsed by Brahmanism nor in its rituals of sacrifice. It became a matter of debate, as is reflected in various texts such as the Mahabharata and the Bhagavad-Gita. Where violence is permitted if it is against evil, as in the Gita, the issue becomes somewhat ambivalent. Who decides that certain actions are evil and opposed to the code of ethics—the Self or the Other? (I shall refer to this discussion again later.) The Buddha’s emphasis on karuna / compassion reflects what was being said about this by various teachers. The emphasis on ahimsa is underlined more frequently in Shramanic teaching than in the other. Of the Vedic corpus, the Upanishads are perhaps more open to these discussions.

The Charvakas were not Shramanas and on occasion their views conflicted. They not only denied the existence of deity but extended this denial to all that cannot be verified. Atheism, rationalism and the need to question was not heresy, it was a right exercised by thinking people. The search was for explaining the real world. We are responsible for our actions and are aware of the consequences. These occur in this life as there is no rebirth. Rituals were rejected and dismissed. A number and variety of such groups debated these ideas and the liveliness sometimes led to entanglements of thought. That is why the Buddha referred to some among them as ‘eel-wrigglers’.

The Shramanas were opposed in varying degrees to Vedic Brahmanism. They questioned the belief in deities, in the Vedas being divinely revealed, in the efficacy of the yajna / ritual of sacrifice, and in the existence of the individual soul or atman. Brahmanical literature refers to the Shramanas categorically as nastika, the non-believers, the astika being the believers. This duality of belief and non-belief remained fundamental to the Brahmanical view of itself and of non-brahmanical religions. It should be differentiated from other dualities in Indian thought. As a term for non-brahmanical belief and practice, nastika continued to be used through the centuries. The concept was not limited to religious thought and it would obviously have carried a social message as well. If deity could be doubted, then so could the laws that were made in the name of the deities as well as the claim of communication between men and gods.

The Shramanas were opposed in varying degrees to Vedic Brahmanism. They questioned the belief in deities, in the Vedas being divinely revealed, in the efficacy of the yajna / ritual of sacrifice, and in the existence of the individual soul or atman. Brahmanical literature refers to the Shramanas categorically as nastika, the non-believers, the astika being the believers. This duality of belief and non-belief remained fundamental to the Brahmanical view of itself and of non-brahmanical religions.

These opposed ideologies underwent many changes as they meandered their way through history. The persons associated with the founding of the more important Shramana religions were from the upper castes, as were many initial followers. Shramanism was open to lower castes who could become lay followers and monks. Rituals were less dramatic than the Vedic ones and were not tied to caste status. Abiding by caste norms was not a criterion of admission to their ranks and the existence of caste was not essential to their teaching. Their dissent was more in the nature of opposing beliefs rather than restructuring society, although the latter was not marginal to their thinking and some restructuring was inevitable. The continuance of caste could be problematic since social ethics was implicit to Shramanic thinking. However, even for the post-Vedic formal religions that evolved around Shaivism and Vaishnavism, the Shramanas were the nastika Others. That Puranic religion was facing a threat is apparent from the mention in the Puranas of dissenters who question the Vedas through false arguments and who can be recognized by their red robes, a reference to the robes worn by the shramana monks.

Apart from their differences of belief religious sects were competitors for royal patronage in the form of donations to their institutions and later there were grants of land to maintain these institutions. Patronage kept the Shramana sects going and gave them a place in society. The competition would doubtless have added to the ideological hostility. The patrons of the shramanas included a large segment of society such as householders owning land or gahapatis, and wealthy merchants or setthis, mercantile guilds and craftsmen and their families, apart from the gradually increasing royal patronage. Their popularity extended to wider levels of society and that would doubtless have added to their ideological differences with Brahmanism.

Ashoka’s visit to the Ramagrama Stupa; relief from the Sanchi Stupa.

Various historical sources refer to two streams of what might be called religion, two dharmas visible on the historical scene. To list a few here: Megasthenes visited Mauryan India in the fourth century BC, coming from the neighbouring Hellenistic Seleucid kingdom in West Asia. He wrote an account of his visit, the Indika. In this he speaks of the seven castes of Indian society of which the highest is divided into two: the Brachmanes and the Sarmanes / the Brahmanas and the Shramanas. The Shramanas, described as philosophers, are not included among the Brahmanas but are listed as distinctive and separate. The edicts of the Mauryan emperor Ashoka issued in the third century BC make repeated pleas for harmony between the various sects. These are often included in the compound phrase in Prakrit bahmanam-samanam when speaking of the sects. The Sanskrit grammarian Patanjali, writing just before the Christian era, compares the antagonism between the brahmana and the shramana to that between the snake and the mongoose.

Various historical sources refer to two streams of what might be called religion, two dharmas visible on the historical scene… Megasthenes visited Mauryan India in the fourth century BC, coming from the neighbouring Hellenistic Seleucid kingdom in West Asia. He wrote an account of his visit, the Indika. In this he speaks of the seven castes of Indian society of which the highest is divided into two: the Brachmanes and the Sarmanes / the Brahmanas and the Shramanas. The Shramanas, described as philosophers, are not included among the Brahmanas but are listed as distinctive and separate. The edicts of the Mauryan emperor Ashoka issued in the third century BC make repeated pleas for harmony between the various sects. These are often included in the compound phrase in Prakrit bahmanam-samanam when speaking of the sects. The Sanskrit grammarian Patanjali, writing just before the Christian era, compares the antagonism between the brahmana and the shramana to that between the snake and the mongoose.

That the differentiation between the two increased over the centuries is apparent from a text that evokes the idea of a conversion to the Buddhist dhamma. Nagasena, a Buddhist monk claims to be recording his conversation about Buddhism with the Indo-Greek king Menander in his text Milinda-panho / The Questions of King Menander. The questions posed and the answers given are fascinating in as much as they draw variously on belief and rational argument. So far no comparable text has been found from the Brahmanical tradition. Perhaps this illustrates one of the fundamental differences between the two in their approach to religion. The brahmana would have regarded Menander as a mleccha and kept him away from participating in the rituals or would have had to bestow upper-caste status on him, whereas the Buddhist was anxious to recruit him as he was, as a Buddhist lay follower.

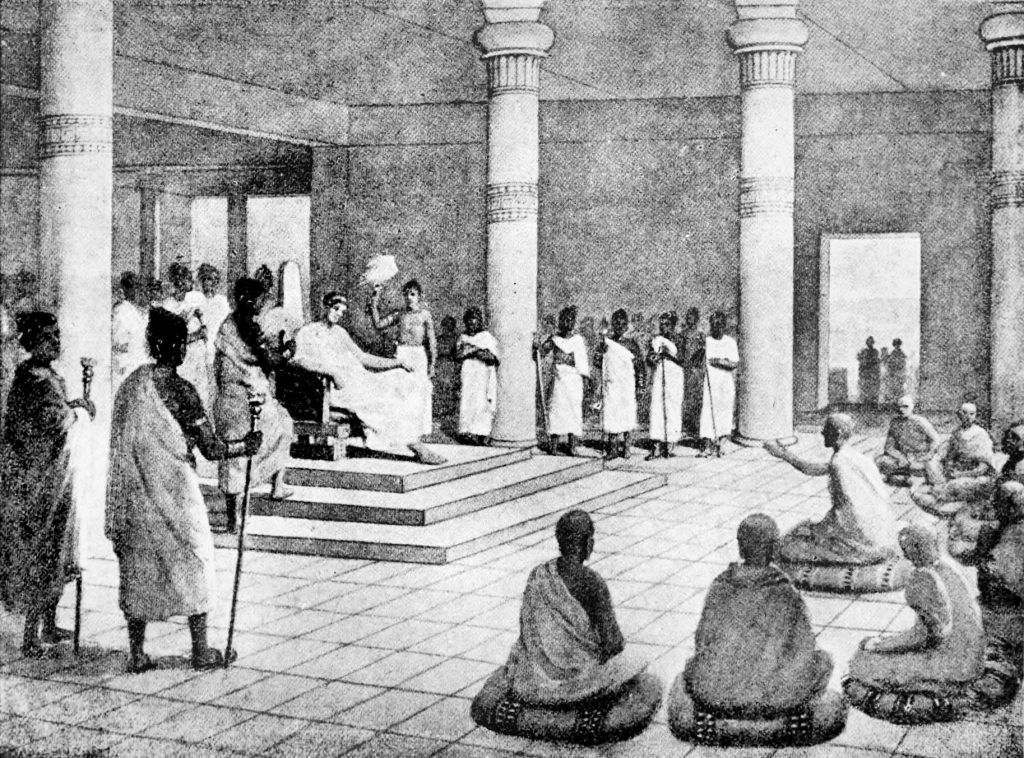

‘King Milinda (Menander) Asks Questions’; sketch from Hutchinson’s Story of the Nations (published before 1923).

Clearly, there were by now many sects with dissenting views. No religion was uniformly observed, nor was it strictly monolithic in its teaching. The two significant traditions of thought are frequently referred to in the sources. This is further confirmed in the early Puranas where hostile remarks on the Shramanas indicate the antagonism between the two. Al-Biruni describes the Brahmana religion at length but also mentions those that are opposed to it as the Sammaniyas.

In the period between the Mauryas and the Guptas, there is a striking presence of impressive Buddhist stupas, and an equally striking absence of temples, a situation that was slowly reversed in the subsequent post-Gupta period. Religious buildings are among the indicators of patronage and popularity. It was a time of intense social change with clan societies giving way to caste societies and many kingdoms being established in areas where earlier there had been clan assemblies, or minimal governmental control, or even none at all. Possibly, it could be said that it was a period when the Shramanas were the more established Selves as it were, and the emerging Puranic Hinduism was a competitor— a position that was reversed in the post-Gupta period. Was the Buddhist Dhammapada facing the dharmashastras of Brahmana authorship more centrally than before? The vision of universal concerns was being slowly recast into the restricted concerns of a caste-bound society.

It was subsequent to this that the Buddhists and Jainas, described as heretics and dissidents in the Puranas of the early centuries AD, began to experience persecution. It seemed to coincide with increasing royal patronage being bestowed on brahmanas. The hostility of Shaiva sects against the Shramanas finds mention, whether in Kashmir or in Tamil Nadu. Buddhist monks and monasteries were attacked in Gandhara as stated in the Rajatarangini of Kalhana, and Jaina monks met a similar fate elsewhere. Why this was so has still to be convincingly explained. Was it just a conflict over patronage between the Puranic and Shramana religions?

The Sanchi Stupa.

In the period between the Mauryas and the Guptas, there is a striking presence of impressive Buddhist stupas, and an equally striking absence of temples, a situation that was slowly reversed in the subsequent post-Gupta period… Possibly, it could be said that it was a period when the Shramanas were the more established Selves as it were, and the emerging Puranic Hinduism was a competitor— a position that was reversed in the post-Gupta period… It was subsequent to this that the Buddhists and Jainas, described as heretics and dissidents in the Puranas of the early centuries AD, began to experience persecution. It seemed to coincide with increasing royal patronage being bestowed on brahmanas… Buddhist monks and monasteries were attacked in Gandhara as stated in the Rajatarangini of Kalhana, and Jaina monks met a similar fate elsewhere. Why this was so has still to be convincingly explained. Was it just a conflict over patronage between the Puranic and Shramana religions?

The Shramana religions were facing their own internal divisions. Buddhism was split into two major schools— the Mahayana / Greater Vehicle, and the Hinayana / Lesser Vehicle. The former had a marked presence in north-western India and Central Asia. Innumerable sects emerged and, based on belief and practice, were connected loosely or firmly to the school of their choice. In subsequent centuries, further schools were added, such as the Vajrayana, influenced by the Tantric religion.

Buddhism tended to be active in a few pockets and more so in eastern India, although for a shorter period. It gradually faded from being foremost among the Shramana religions having conceded ground to the idea of deity and related practices. Its decline was furthered by other socioeconomic changes. A decline in commerce doubtless affected its patronage as did the diversion of royal donations elsewhere. The argument that Islam dealt a death-blow to Buddhism in India is untenable since Buddhism had ceased to be pre-eminent even before the coming of Islam to North India. This is suggested by the assessment of the seventh-century AD Chinese Buddhist monk Xuanzang, who travelled widely in India and eventually spent a few years studying in Nalanda.

Portrait of Xuanzang (Genjō) with Attendant, 14th Century.

As a contrast to Buddhism’s quietude in India, this was the period when it had a spectacular following in most parts of Asia. Buddhist missionary activity marked a major difference from other Indian religions that tended to be stay-at-home. Buddhist monks pioneered missions to Central Asia in the early centuries AD, travelling with the merchants active in establishing trade links along many routes that have come to be called the Silk Routes. They also travelled along the maritime trade routes through South-East Asia. Curiously, Puranic Hinduism that also did a modicum of travelling at this time, and through the same channels as Buddhism, remained a marginal religion if at all in most places. In South-East Asia it offered some competition initially but eventually gave way to Buddhism.

The Jainas survived perhaps by consolidating their patronage and rooting themselves in specific areas such as Karnataka and Western India, supported substantially by the wealthy mercantile community and occasionally by royalty. The teaching was largely split into two major schools, the Digambara and the Shvetambara, each with many sects. Their monasteries became centres of scholarship focusing on their own teaching and thus forming a kind of counterpart to the mathas of the brahmanas. Many had a proficiency in accounting and finance that linked them to the commercial activities of those times and to the lives of trading communities. Possibly some concession was made here or there in ritual and worship, as in the spectacular temples they built, that indicated their well-being. This again has to be examined.

Among the philosophical Others that we often dismiss were the materialist philosophers of the Charvaka teaching. They are neglected because of our obsession with the idea that India has only respected non-materialist philosophies in the past. Unfortunately, there is no surviving text of major significance that they authored on their philosophy, much of it being taught orally. Had there been some texts, then they would have been given greater space. There are, however, references to them and summaries of their teachings in diverse texts. Some regard the Arthashastra as a text that shows traces of Charvaka thinking. This may be because Kautilya underlines the importance of critical enquiry, with an emphasis on tarka / logic. This may suggest that dissent was latent in various schools of Indian thought and we have to be more sensitive to its presence.

In the Mahabharata, a rakshasa named Charvaka upbraids Yudhishthira on the futility of the killing that resulted from the battle at Kurukshetra. He is silenced when he is himself killed by the brahmanas present. Buddhist texts were also not, on the whole, friendly towards the Charvakas, even though the teaching of both was opposed to that of the brahmanas. Gradually, there developed a tendency for Brahmanical texts to list the non-Brahmanical schools altogether in one list and describe them all as nastika / non-believers.

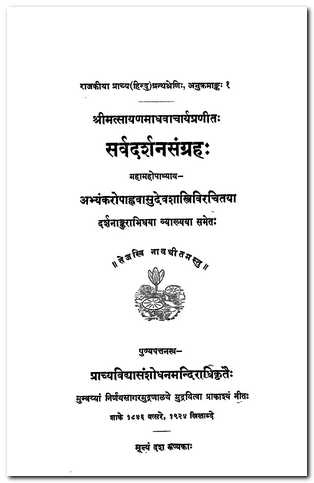

Sarva-darshana-samgraha

However, it would seem that Charvaka thinking was present through the centuries to medieval times. A compendium of current fourteenth-century philosophies, the Sarva-darshana-samgraha, written by Madhvacharya, a philosopher of the time, has as its opening chapter a discourse on Charvaka philosophy. The author explains that although he himself did not agree with its arguments, it was nevertheless a known school of thought. This suggests that the philosophy of materialism was present both among philosophers and others. We are also told that when Emperor Akbar invited representatives of various philosophical schools, the Charvakas were one among them. We need to restore them to their rightful place in our assessment of the philosophical spectrum in Indian thought. Even if this is not stated directly, they are likely to have been in dialogue with the other streams, else they would have faded out before the fourteenth century. Of the two main streams, the dialogue of the Charvakas would more likely have been with the Shramanas.

Among the philosophical Others that we often dismiss were the materialist philosophers of the Charvaka teaching. They are neglected because of our obsession with the idea that India has only respected non-materialist philosophies in the past. Unfortunately, there is no surviving text of major significance that they authored on their philosophy, much of it being taught orally… We need to restore them to their rightful place in our assessment of the philosophical spectrum in Indian thought. Even if this is not stated directly, they are likely to have been in dialogue with the other streams, else they would have faded out before the fourteenth century.

So much by way of a very brief sketch of the background.

Dissent that uses the idiom of religion, as did many pre-modern dissenting groups, did not confine itself to writing dissenting texts. It is not enough to look only at the texts that resulted from conflicting ideas, although this is a necessary step. These provide some of the explanation that gave rise to dissent. It is equally important to study the institutions that religious groups built to support their activities and through which conformity or dissent was expressed. In some instances, these had more than a marginal role in formulating either the one or the other. I shall refer to just a few examples to illustrate the point.

The Shramanas established a new personality on the social landscape—that of the renouncer. This entity occasionally took on the characteristics of a counterculture. It was a new kind of Other. The renouncers as monks lived separately in their own institutions—the monasteries that were sometimes identified by sect. They were dependent on society for alms, mainly food. They broke the rules of caste by being celibate, by eating cooked food given by anyone irrespective of caste, and (in theory at least) by not segregating the savarna, those belonging to a varna / caste, from the avarna, those without a varna identity. The well-established sects among these intervened in politics and social concerns although claiming to be focused on religion, a situation that continues to this day in the nexus between many religious sects and politics and in the political activities of religious organizations. Patronage is frequently the link. The renouncer opting out of society but claiming to have the welfare of society as his concern acquires a degree of moral authority within society, and this can increase in accordance with his teaching and activity. This was a feature of pre-modern times and, as we shall see, is not unknown to modern times as well.

In order to maintain the institutions of the renouncers, the granting of land and large donations towards their maintenance continued. It enabled them to become powerful social and political institutions but their role as Others gradually diminished. Donations to brahmanas as individuals or as groups or as institutions helped in building up a strong religious base for Brahmanism, as had earlier been so for Buddhism. The institutionalizing of a religion inevitably gives it a certain control over secular functioning. It subsumes the secular into the religious authority. The multitude of inscriptions from the late first millennium AD recording grants of land and wealth donated to brahmanas gave to Brahmanism a larger political and economic status than merely the role of ritual specialists conducting Vedic sacrificial and other rituals, building temples and worshipping icons placed therein. Inevitably the religion itself underwent a shift.

The success of Brahmanism in unsettling the Shramanas was in part due to brahmanas now receiving a large share of patronage. Royal patronage to Vedic Brahmanism continued but had also to adjust to the growing demands of the institutions of a form of Hinduism that might be better referred to as Puranic Hinduism. This was the worship of various manifestations of Vaishnavism and Shaivism to begin with and later included the Shakta-Shakti and other cults. Within these larger assemblages were included on occasion some local deities inducted into the Puranic pantheon. When this happened, the ritual specialists either became a separate caste category or were drawn into the brahmana caste. Evidence of this is more common after the Gupta period. In some ways it is minimally reminiscent of the brahmana sons of dasis being given brahmana status. Local deities could be from another tradition, but if it was expedient to induct them into Puranic Hinduism, it was done.

Dissent that uses the idiom of religion, as did many pre-modern dissenting groups, did not confine itself to writing dissenting texts. It is not enough to look only at the texts that resulted from conflicting ideas, although this is a necessary step. These provide some of the explanation that gave rise to dissent. It is equally important to study the institutions that religious groups built to support their activities and through which conformity or dissent was expressed.

In fact, Puranic Hinduism, although it invokes Vedic Brahmanism, was in many respects distinct. Some of its major features suggest a reaction to the competition with Shramanism. This would be an example of dissent helping to engineer a new formulation of an existing religion. Its texts were the Puranas, composed in a more widely spoken Sanskrit than the now-rather-archaic Vedic Sanskrit of the Vedas, and in later centuries even more in local languages. The study and recitation of the Vedas was restricted to appropriate people, but the Puranas were recited and made familiar to popular audiences. Unlike the major Vedic sacrificial rituals that were not associated with the worship of idols and could be performed wherever thought suitable, and whose locations were disbanded at the conclusion of the ritual, Puranic Hinduism now began building permanent places of worship, namely, temples housing images of deities with an increasing focus on their worship, and accompanying the changes in the religion. These innovations are reflected in the late dharma-shastras where, for example, there is a discussion on which brahmana is to be given priority—the one who is a specialist in the Vedas or the temple priest.

Beginning as places housing icons being worshipped, temples were to gradually become immensely large and complex institutions supported by the offerings of the worshippers and the donations of land and money by wealthy patrons. All this had to be administered by a large body of priests. They also became major places of pilgrimage, and with gatherings of people from a variety of places, they doubled up as commercial centres that in turn gave them an added economic importance.

Buddhist Vihara, Nalanda University.

The Shramanas had their institutions that impinged on society in the form of viharas / monasteries, chaityas / halls of worship and stupas / relic mounds. Puranic Hinduism had its institutions that were entirely different in the form of temples and of mathas / centres of textual religion and learning. That religious institutions were extending their reach over the socioeconomic and political activities of the time becomes evident. This brought about a change from earlier times in the inter-relation between religion and society. It was no longer limited to religion providing a path to worship, since it now extended to religious institutions intervening in the activities of society. Patronage was absolutely crucial to the continuance of these socio-religious institutions.

There was a gradual shift in patronage, especially among royal families with greater support going to the brahmanas who by now were increasingly the authors and the ritual specialists of Puranic Hinduism. Two obvious factors might explain this change. The brahmanas could supply the upstart dynasties with lineage links to ancient kshatriya genealogies to legitimize their being called the new kshatriyas as many were; and the claim of the brahmanas that they could perform effective rituals to avert evil and bad luck in order to ensure the continuous and successful rule of these dynasties.

Coinciding with this, patronage from wealthy merchants and guilds to the Shramana institutions possibly declined in this period when there was a fall in trade and wealth to donate was not easily available. Monasteries and trading groups had a close connection with the former, sometimes as participants in commercial activities. Changes in the volume of trade would therefore decrease the patronage available to monasteries and thereby curtail their activities.

Puranic Hinduism, although it invokes Vedic Brahmanism, was in many respects distinct. Some of its major features suggest a reaction to the competition with Shramanism. This would be an example of dissent helping to engineer a new formulation of an existing religion. Its texts were the Puranas, composed in a more widely spoken Sanskrit than the now-rather-archaic Vedic Sanskrit of the Vedas, and in later centuries even more in local languages. The study and recitation of the Vedas was restricted to appropriate people, but the Puranas were recited and made familiar to popular audiences. Unlike the major Vedic sacrificial rituals that were not associated with the worship of idols and could be performed wherever thought suitable, and whose locations were disbanded at the conclusion of the ritual, Puranic Hinduism now began building permanent places of worship, namely, temples housing images of deities with an increasing focus on their worship, and accompanying the changes in the religion.

Nevertheless, this period saw substantial scholarship both among the shramanas and the brahmanas in a remarkable articulation of philosophical ideas. Given that the premises of each were so different, there was naturally much debate that drew on both orthodoxy and dissent. Dissent was not restricted to the instituting of renunciatory orders. It also focused on the discussion of philosophical ideas. Debates were known to take place at royal courts, as, for instance, at that of Harshavardhana, the seventh-century ruler of Thanesar-Kanauj. Among the well-known philosophers of around that period were Dignaga and Dharmakirti. Subsequently, the practice is associated with Shankaracharya and others.

Even within what may broadly be called the different Shramana traditions, there evolved a large range of sects that differed among themselves and asserted a degree of autonomy. The differences focused on the interpretation of the teachings of the founders, on the rules of the monastic orders, and on the precepts required to be observed by lay followers. Such differences could be theological in origin or more often due to a changing historical context.

For instance, when the money economy gained currency in early times, an obvious question arose as to whether monks could accept donations of money, and this was one of the causes of a rift in the early Buddhist Sangha. Later when patrons and donors included more than just the lay following and registered gifts from diverse categories such as royalty and mercantile interests, the particular requirements of each of these categories had to be accommodated. Large donations of land generally from royalty led to what Max Weber described as monastic landlordism. This was counter to the rule that the monastery should not own property, and more so when the landed property was so large that it required the monks to do administrative work and supervise the labour employed to work the land. In such situations, the monastery was also a socioeconomic institution not entirely divorced from political connections. As such its nurturing of dissent might have been muted. The imprint of having to administer landed property would also have altered the patterns of living in the mathas and agraharas of the brahmanas, not to mention the richly endowed temples. Not all brahmanas could spend their time studying the texts, for some among them had to supervise the farming and its ancillary produce and some others had to keep the accounts in order. The monks of the monasteries were familiar with these procedures.

From the mid-first millennium AD, the Shramanic religions were not invariably dissenting groups in relation to the increasingly well-endowed Puranic Hinduism. By this time, they had evolved both their own orthodoxies and their own dissenting ideas and practices vis-à-vis these orthodoxies. The survival of these varied.

From the mid-first millennium AD, the Shramanic religions were not invariably dissenting groups in relation to the increasingly well-endowed Puranic Hinduism. By this time, they had evolved both their own orthodoxies and their own dissenting ideas and practices vis-à-vis these orthodoxies. The survival of these varied.

Virtually every religion in India consisted by now of multiple sects, each seeking its own patronage and asserting its identity. This pattern was applicable to later religions as well. Having an institution and an identity helped in locating it in the gamut of sects and this allowed it to be characterized as conforming to or dissenting from, or locating itself somewhere in-between the original teaching and its variant. The feasibility of differences and their coexistence was recognized, although some among them faced animosity and conflict. But in either case, the relationship between sects, whether friendly or hostile, was confined to small, local groups. A single, uniformly applicable, overarching religion was unfamiliar. Nor was there a single sacred overarching text even for what might be taken as a formal religion. A canon was recognized by some of the followers but no text was singled out as unquestionably the single and most sacred one over and above all others. This made the localization of religious practices and ideas far stronger than the somewhat abstract loyalty to an overarching single text.

Later when attempts were made to write on past events linked to the religion, these tended to be potted histories or documented recalls of the sect rather than a story of the larger religion. Even where they began with the larger story, they moved into the particulars of the sect. The Shramana religions had better documentation on their pasts but this may have been because they were rooted in the thoughts of a historical founder, and they were initially dissident groups that made it a point to construct and recall the past, perhaps in part to give themselves legitimacy. One of the purposes of claiming a history is to claim legitimacy. Today, however, we require that the history not be a casual narrative, but be such that it draws on reliable evidence for supporting the claim.

Interestingly, this was also a time when the notion of heresy was spoken of more frequently in a variety of texts, such as the Puranas. This is significant since the Puranas were the texts that gave a formal structure to Puranic Hinduism. Heresy takes on a force when dissent from a canonical position becomes apparent and audible, when a lay following and competition for patronage increases, and when the institutional base of orthodoxy requires larger investments of wealth.

The success of Brahmanism in the later first millennium meant that it faced all these problems to a greater extent than before. Heresy was not limited to the erstwhile Other as it now crept into the ambitions of various sects previously within the confines of the thought and life of the Self. The relationship between the Shaiva and Vaishnava sects in the context of yet another stream—that of the Shaktas—would be worth investigating from this perspective. To what degree was there a rivalry among them? Or were there mutual adjustments? Were they linked to a potential following? The term pashanda initially applied to any sect now shifted in meaning and began to refer specifically to those sects that were being condemned as fraudulent by the more conservative. The point at which a religion recognizes that it has orthodoxy is often also the moment when a heterodoxy opposing it becomes apparent.

This was also a time when the notion of heresy was spoken of more frequently in a variety of texts, such as the Puranas… that gave a formal structure to Puranic Hinduism. Heresy takes on a force when dissent from a canonical position becomes apparent and audible, when a lay following and competition for patronage increases, and when the institutional base of orthodoxy requires larger investments of wealth… Heresy was not limited to the erstwhile Other as it now crept into the ambitions of various sects previously within the confines of the thought and life of the Self. The relationship between the Shaiva and Vaishnava sects in the context of yet another stream—that of the Shaktas—would be worth investigating from this perspective.

The emergence of these renouncers took on the characteristics of what may be called a counter-culture, at least to begin with. It was an entirely new kind of Other. It should not be confused with the ascetic with which it often is. The renouncer may have had traces of the ascetic but was actually quite distinct.

The one who wished to become an ascetic, the samnyasi, performed the funerary rituals that would have been required for him. He cut his ties with family and society, and went to live in isolation. Sometimes he would visit an ashrama in some distant place where other ascetics were living but essentially he was supposed to live away from others. This idea has of course disappeared from the many institutions that call themselves ashramas today and are anything but socially isolated. The ascetic’s purpose was to search for ways to liberate his soul from rebirth. On his death he was not to be cremated but to be buried in a sitting position.

The renouncer, by joining an Order or a sect, renounced his prior social identity and assumed a new one as a member of that Order or sect. Family ties were not entirely discontinued. He did not regard himself as severed from society as the sects accepted patronage from virtually anyone who gave it, and worked towards acquiring a large lay following of people by convincing them of the teaching of the founders—at least of that version of the teaching which was being propagated by the particular sect he belonged to. The teaching was not conversion to a new religion but was intended more to give people a new ethical ideal. The Shramanas emphasized the centrality of improving the social good.

Renunciation is not a necessary component of dissent, but where it exists there is some element of dissent. To consider the views of the latter as we know does make for a greater representation of diverse opinion. Using this experience of the past and questioning the activities of the present can help define a better future. This, after all, was part of the purpose in imagining and projecting the future in the form of a millennial utopia, to be ushered in by the Buddha to come, the Buddha Maitreya.

The Shramana tradition recognized the difference in status given by society to men and to women. It did concede giving the choice of renunciation to women and quite a few took it. They had to get the consent of their husbands if they were married. Even women who were not from elite groups could make donations to the Buddhist Sangha and their donations were recorded. But it was not a choice that allowed autonomy to women since nuns were to be essentially subservient to the orders and the teaching of the monks. It did however assist in persuading women to become lay followers. Respect for nuns was not universal. According to one dharma-shastra, respectable women should have no communication with nuns. The Arthashastra states repeatedly that Buddhist and Jaina nuns can be employed as spies by the royal court. One wonders whether it was actually so or whether this was said to cast suspicion on the nuns.

Jain Temple, Nagarparkar.

Since they had a commitment to the welfare of society, the monks remained connected with the lay following. Unlike the ashramas—the forest hermitages of earlier times—these monasteries located near villages and towns were the institutional spine of the Buddhist and Jaina religions and, as such, had a marked presence in society. Their effective interventions may have encouraged other religious sects to establish similar institutions. When brahmanas received land grants of agraharas and when they established their mathas, there was a striking increase in their presence in the more fertile and wealthier parts of kingdoms. The same pattern can be noticed, not surprisingly, with the coming of the Sufis and their founding khanqahs and dargahs in the agriculturally and commercially richer areas, where patronage was forthcoming. For instance, there was much Sufi activity in the Multan region of southern Punjab and in the upper Doab with the arrival of the first Sufis. Important trade routes ran through this area and irrigation systems were introduced.

The institution encapsulating the teaching became the focus. A range of religious sects adopted this institutional form as they do to this day. Monasteries were locations for the study of religious and philosophical ideas and for meditation but many, in the course of just being present in the proximity of villages and towns, extended their concerns to matters political and social, expanding their range of Otherness. Their extension into taking on the function of social institutions imbued them with the power and authority that they required to formulate the codes by which communities would search for an identity. In this situation, dissent might still have had a religious form but in effect it began to relate to a greater degree to social concerns.

Since they had a commitment to the welfare of society, the monks remained connected with the lay following. Unlike the ashramas—the forest hermitages of earlier times—these monasteries located near villages and towns were the institutional spine of the Buddhist and Jaina religions and, as such, had a marked presence in society. Their effective interventions may have encouraged other religious sects to establish similar institutions. When brahmanas received land grants of agraharas and when they established their mathas, there was a striking increase in their presence in the more fertile and wealthier parts of kingdoms. The same pattern can be noticed, not surprisingly, with the coming of the Sufis and their founding khanqahs and dargahs in the agriculturally and commercially richer areas, where patronage was forthcoming… The institution encapsulating the teaching became the focus. A range of religious sects adopted this institutional form as they do to this day. Monasteries were locations for the study of religious and philosophical ideas and for meditation but many, in the course of just being present in the proximity of villages and towns, extended their concerns to matters political and social, expanding their range of Otherness.

Their becoming wealthy and well established coincided with orthodoxies arising in these institutions and this, in turn, opened up some of them to further dissenting opinion. Earlier dissenting groups were also subjected to new concepts of disagreement and the pattern that emerged demonstrated the potential of being the Other. What was open to negotiation, depending on the focus of dissent, was the question of whether the dissent was helping to strengthen orthodoxy or was encouraging heterodoxy. All Shramana sects were not necessarily centres of dissent since there were debates within the overall thinking of their views. Similarly, there were disagreements among sects following other religious ideas. Dissent therefore has to be seen in relation to who is the particular Self.

Not all renouncers joined institutions and communities. There were individual renouncers who moved across the historical landscape in diverse forms, such as the sadhu, faqir, jogi, and were recognized as part of the larger category of the Other—but in their individual capacity. The renouncer opting out of society to work for the good of all gave him a status, and he acquired moral authority within society. This seems somewhat contradictory but it gave legitimacy to his dissent and to the social ethics that he taught, dissenting as he was from the views of the dominant groups. If he attracted supporters, then this in turn gave him a social leverage. Was this perhaps the reason why Kautilya, supporting authoritarian rule, discourages the state from allowing renouncers to enter newly settled lands? Presumably, the argument would be that if the state wishes to exercise complete power, it should disallow dissenting views—familiar from many histories of the past and the present. Where the state controlled the varied aspects of society as was advocated in the Arthashastra, this dictatorial authority gave it the power to disallow dissenting views.

We have to keep in mind that not all ‘holy men’ have arrived at renunciation or semi-renunciation after a serious understanding of why they have done so. Some adopt the symbols associated with holiness as individuals only to exploit them for personal advantage. There is something of a gamble in knowing how far the concern is real. Renunciation can be a genuine act of faith or it can be a disguise for exploiting the faith of others; hence the need to check the authenticity of the claims. There also has to be a balance of emphasis on the message or on the religious symbols and idioms. If the message is too heavily encumbered by the latter, it loses its force.

The period between the Mauryan and Gupta times was one of some competition for superiority, even if indirectly among sects. Hovering over the statements on political activities in the Manu Dharmashastra and the Kautilya Arthashastra is the fear of anarchy. A condition of anarchy is described as matsyanyaya, when the big fish eat the little fish. The texts speak of pervading evil and the wicked not being punished, without defining exactly who is meant by these references. Nevertheless, it is interesting that it is the activities of the big fish that crystallize the sense of anarchy.

Yet, in periods of emergency, Kautilya permits the king to confiscate the wealth of a religious institution. Later historical examples of this are described in detail in Kalhana’s Rajatarangini, where we are told that towards the end of the first millennium AD various rulers of Kashmir used the excuse of a fiscal crisis to loot temples, culminating in the horrendous attacks on temples by the eleventh-century ruler Harshadeva.

Curiously, despite all these changes and challenges to existing norms, there seems to have been some hesitation in dissent turning into revolt. Dissent was perhaps a way of containing it. The awareness of the possibility of revolt was known but discouraged. Caste rules could be quietly reformulated as long as no questions were asked, or people could get away with it; new deities and rituals were incorporated into the formal religions, and occasionally new teaching hinting at a different kind of society could be spoken of among some people. This has been an ongoing process through the centuries—and explains the acceptance of interpolations into texts such as the Mahabharata, Ramayana and Gita. Through these interpolations, the texts were, as it were, living with the times.

Curiously, despite all these changes and challenges to existing norms, there seems to have been some hesitation in dissent turning into revolt. Dissent was perhaps a way of containing it. The awareness of the possibility of revolt was known but discouraged. Caste rules could be quietly reformulated as long as no questions were asked, or people could get away with it; new deities and rituals were incorporated into the formal religions, and occasionally new teaching hinting at a different kind of society could be spoken of among some people.

The migration of discontented peasants from one kingdom to another is referred to, although it is disapproved of by the rulers since it resulted in a loss of revenue. As it has been argued, if peasants migrate, then it can be understood that they are agitating against an oppressive authority. But the right of subjects to revolt is not easily conceded in the texts of the earlier period. The Mahabharata allows the assassination of oppressive kings but only by those capable of making such a judgement such as the brahmanas. Buddhist sources, though, are more flexible.

This flexibility may be an outcome of the Buddhist view on the origin of the state, repeated in the Mahabharata. It is narrated that when the pristine utopia of human society began to decline with the introduction of kinship rules and ownership of property determining social-behaviour, the people affected by this change gathered and elected one from among themselves to make laws and to rule over them in accordance with the laws. This notion of what can almost be called a social contract is consistent in Buddhist writing. In the texts authored by brahmanas, this comes at a later stage, the earlier argument favouring the raja being appointed by a deity.

References to peasants threatening to revolt appear to be made more frequently in the second millennium AD, but these may just have been rhetorical. Actual disturbances are few. Similarly, when some urban artisans also objected to the amount of taxes and rents they had to pay, an agreement was negotiated.

This excerpt has been carried courtesy the permission of Seagull Books. You can buy Voices of Dissent: An Essay here.

Romila Thapar is Emeritus Professor of History at Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi. She has been General President of the Indian History Congress. She is a Fellow of the British Academy and holds honorary doctorates from Universities of Calcutta, Oxford and Chicago, among others. She is an Honorary Fellow of Lady Margaret Hall, Oxford, and SOAS, London. She has edited and written several books including Aśoka and the Decline of the Mauryas, Ancient Indian Social History: Some Interpretations, Somanatha: the Many Voices of a History, A History of India (Volume One), and Early India: From the Origins to AD 1300. Her area of specialisation is in early Indian history. In 2008 she was awarded the prestigious Kluge Prize of the Library of Congress, USA. You can read more about her and her work here.

| 2500 BC - Present | |

|

2500 BC - Present |

| Tribal History: Looking for the Origins of the Kodavas | |

| 2200 BC to 600 AD | |

|

2200 BC to 600 AD |

| War, Political Violence and Rebellion in Ancient India | |

| 400 BC to 1001 AD | |

|

400 BC to 1001 AD |

| The Dissent of the ‘Nastika’ in Early India | |

| 600CE-1200CE | |

|

600CE-1200CE |

| The Other Side of the Vindhyas: An Alternative History of Power | |

| c. 700 - 1400 AD | |

|

c. 700 - 1400 AD |

| A Historian Recommends: Representing the ‘Other’ in Indian History | |

| c. 800 - 900 CE | |

|

c. 800 - 900 CE |

| ‘Drape me in his scent’: Female Sexuality and Devotion in Andal, the Goddess | |

| 1192 | |

|

1192 |

| Sufi Silsilahs: The Mystic Orders in India | |

| 1200 - 1850 | |

|

1200 - 1850 |

| Temples, deities, and the law. | |

| c. 1500 - 1600 AD | |

|

c. 1500 - 1600 AD |

| A Historian Recommends: Religion in Mughal India | |

| 1200-2020 | |

|

1200-2020 |

| Policing Untouchables and Producing Tamasha in Maharashtra | |

| 1530-1858 | |

|

1530-1858 |

| Rajputs, Mughals and the Handguns of Hindustan | |

| 1575 | |

|

1575 |

| Abdul Qadir Badauni & Abul Fazl: Two Mughal Intellectuals in King Akbar‘s Court | |

| 1579 | |

|

1579 |

| Padshah-i Islam | |

| 1550-1800 | |

|

1550-1800 |

| Who are the Bengal Muslims? : Conversion and Islamisation in Bengal | |

| c. 1600 CE-1900 CE | |

|

c. 1600 CE-1900 CE |

| The Birth of a Community: UP’s Ghazi Miyan and Narratives of ‘Conquest’ | |

| 1553 - 1900 | |

|

1553 - 1900 |

| What Happened to ‘Hindustan’? | |

| 1630-1680 | |

|

1630-1680 |

| Shivaji: Hindutva Icon or Secular Nationalist? | |

| 1630 -1680 | |

|

1630 -1680 |

| Shivaji: His Legacy & His Times | |

| c. 1724 – 1857 A.D. | |

|

c. 1724 – 1857 A.D. |

| Bahu Begum and the Gendered Struggle for Power | |

| 1818 - Present | |

|

1818 - Present |

| The Contesting Memories of Bhima-Koregaon | |

| 1831 | |

|

1831 |

| The Derozians’ India | |

| 1855 | |

|

1855 |

| Ayodhya 1855 | |

| 1856 | |

|

1856 |

| “Worshipping the dead is not an auspicious thing” — Ghalib | |

| 1857 | |

|

1857 |

| A Subaltern speaks: Dalit women’s counter-history of 1857 | |

| 1858 - 1976 | |

|

1858 - 1976 |

| Lifestyle as Resistance: The Curious Case of the Courtesans of Lucknow | |

| 1883 - 1894 | |

|

1883 - 1894 |

| The Sea Voyage Question: A Nineteenth century Debate | |

| 1887 | |

|

1887 |

| The Great Debaters: Tilak Vs. Agarkar | |

| 1893-1946 | |

|

1893-1946 |

| A Historian Recommends: Gandhi Vs. Caste | |

| 1897 | |

|

1897 |

| Queen Empress vs. Bal Gangadhar Tilak: An Autopsy | |

| 1913 - 1916 Modern Review | |

|

1913 - 1916 |

| A Young Ambedkar in New York | |

| 1916 | |

|

1916 |

| A Rare Account of World War I by an Indian Soldier | |

| 1917 | |

|

1917 |

| On Nationalism, by Tagore | |

| 1918 - 1919 | |

|

1918 - 1919 |

| What Happened to the Virus That Caused the World’s Deadliest Pandemic? | |

| 1920 - 1947 | |

|

1920 - 1947 |

| How One Should Celebrate Diwali, According to Gandhi | |

| 1921 | |

|

1921 |

| Great Debates: Tagore Vs. Gandhi (1921) | |

| 1921 - 2015 | |

|

1921 - 2015 |

| A History of Caste Politics and Elections in Bihar | |

| 1915-1921 | |

|

1915-1921 |

| The Satirical Genius of Gaganendranath Tagore | |

| 1924-1937 | |

|

1924-1937 |

| What were Gandhi’s Views on Religious Conversion? | |

| 1900-1950 | |

|

1900-1950 |

| Gazing at the Woman’s Body: Historicising Lust and Lechery in a Patriarchal Society | |

| 1925, 1926 | |

|

1925, 1926 |

| Great Debates: Tagore vs Gandhi (1925-1926) | |

| 1928 | |

|

1928 |

| Bhagat Singh’s dilemma: Nehru or Bose? | |

| 1930 Modern Review | |

|

1930 |

| The Modern Review Special: On the Nature of Reality | |

| 1932 | |

|

1932 |

| Caste, Gandhi and the Man Beside Gandhi | |

| 1933 - 1991 | |

|

1933 - 1991 |

| Raghubir Sinh: The Prince Who Would Be Historian | |

| 1935 | |

|

1935 |

| A Historian Recommends: SA Khan’s Timeless Presidential Address | |

| 1865-1928 | |

|

1865-1928 |

| Understanding Lajpat Rai’s Hindu Politics and Secularism | |

| 1935 Modern Review | |

|

1935 |

| The Modern Review Special: The Mind of a Judge | |

| 1936 Modern Review | |

|

1936 |

| The Modern Review Special: When Netaji Subhas Bose Was Wrongfully Detained for ‘Terrorism’ | |

| 1936 | |

|

1936 |

| Annihilation of Caste: Part 1 | |

| 1936 Modern Review | |

|

1936 |

| The Modern Review Special: An Indian MP in the British Parliament | |

| 1936 | |

|

1936 |

| Annihilation of Caste: Part 2 | |

| 1936 | |

|

1936 |

| A Reflection of His Age: Munshi Premchand on the True Purpose of Literature | |

| 1936 Modern Review | |

|

1936 |

| The Modern Review Special: The Defeat of a Dalit Candidate in a 1936 Municipal Election | |

| 1937 Modern Review | |

|

1937 |

| The Modern Review Special: Rashtrapati | |

| 1938 | |

|

1938 |

| Great Debates: Nehru Vs. Jinnah (1938) | |

| 1942 Modern Review | |

|

1942 |

| IHC Uncovers: A Parallel Government In British India (Part 1) | |

| 1943-1945 | |

|

1943-1945 |

| Origin Of The Azad Hind Fauj | |

| 1942-1945 | |

|

1942-1945 |

| IHC Uncovers: A Parallel Government in British India (Part 2) | |

| 1946 | |

|

1946 |

| Our Last War of Independence: The Royal Indian Navy Mutiny of 1946 | |

| 1946 | |

|

1946 |

| An Artist’s Account of the Tebhaga Movement in Pictures And Prose | |

| 1946 – 1947 | |

|

1946 – 1947 |

| “The Most Democratic People on Earth” : An Adivasi Voice in the Constituent Assembly | |

| 1946-1947 | |

|

1946-1947 |

| VP Menon and the Birth of Independent India | |

| 1916 - 1947 | |

|

1916 - 1947 |

| 8 @ 75: 8 Speeches Independent Indians Must Read | |

| 1947-1951 | |

|

1947-1951 |

| Ambedkar Cartoons: The Joke’s On Us | |

| 1948 | |

|

1948 |

| “My Father, Do Not Rest” | |

| 1940-1960 | |

|

1940-1960 |

| Integration Myth: A Silenced History of Hyderabad | |

| 1948 | |

|

1948 |

| The Assassination of a Mahatma, the Princely States and the ‘Hindu’ Nation | |

| 1949 | |

|

1949 |

| Ambedkar warns against India becoming a ‘Democracy in Form, Dictatorship in Fact’ | |

| 1950 | |

|

1950 |

| Illustrations from the constitution | |

| 1951 | |

|

1951 |

| How the First Amendment to the Indian Constitution Circumscribed Our Freedoms & How it was Passed | |

| 1967 | |

|

1967 |

| Once Upon A Time In Naxalbari | |

| 1970 | |

|

1970 |

| R.C. Majumdar on Shortcomings in Indian Historiography | |

| 1973 - 1993 | |

|

1973 - 1993 |

| Balasaheb Deoras: Kingmaker of the Sangh | |

| 1975 | |

|

1975 |

| The Emergency Package: Shadow Power | |

| 1975 | |

|

1975 |

| The Emergency Package: The Prehistory of Turkman Gate – Population Control | |

| 1977 – 2011 | |

|

1977 – 2011 |

| Power is an Unforgiving Mistress: Lessons from the Decline of the Left in Bengal | |

| 1984 | |

|

1984 |

| Mrs Gandhi’s Final Folly: Operation Blue Star | |

| 1916-2004 | |

|

1916-2004 |

| Amjad Ali Khan on M.S. Subbulakshmi: “A Glorious Chapter for Indian Classical Music” | |

| 2008 | |

|

2008 |

| Whose History Textbook Is It Anyway? | |

| 2006 - 2009 | |

|

2006 - 2009 |

| Singur-Nandigram-Lalgarh: Movements that Remade Mamata Banerjee | |

| 2020 | |

|

2020 |

| The Indo-China Conflict: 10 Books We Need To Read | |

| 2021 | |

|

2021 |

| Singing/Writing Liberation: Dalit Women’s Narratives | |

Enlighening