As India’s first Prime Minister, Jawaharlal Nehru occupies a unique position in the history of Modern India. He laid down precedents and expectations regarding how things were supposed to be in a democracy. But to trace the history of his ideas, without delving into the philosophies and ideologies of his contemporaries, the significant leaders and thinkers who participated in the Indian National Movement, seems like an impossible task.

And we may not be the only ones to claim the significance of these contemporaries and their ideologies.

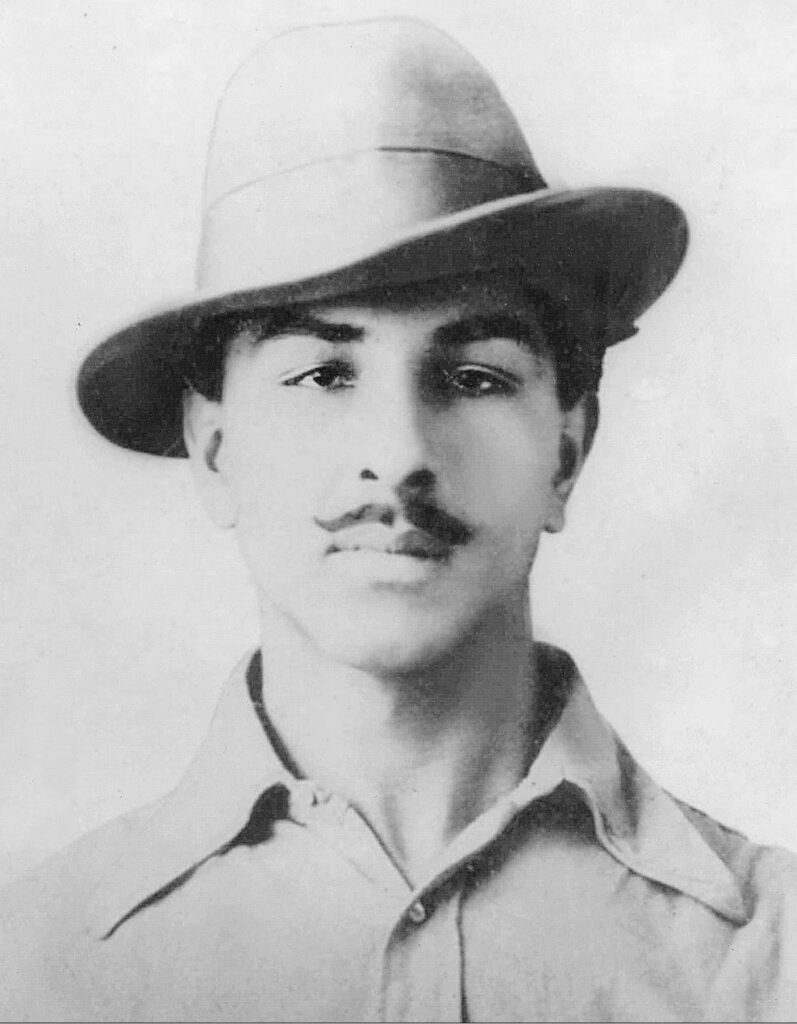

At 21 years of age, in 1928, Bhagat Singh, “an astonishingly mature and deeply political thinker” (Purushottam Agrawal), published an article in the journal ‘Kirti’, titled ‘Naye Netaon ke Alag-Alag Vichar’, an English translation of which (titled ‘New Leaders and their Different Ideologies’) is reproduced below.

Singh, as is understood in the popular context of his historical role in the Indian freedom struggle, was a ‘revolutionary’ — a school of thought that perhaps also included Subhash Chandra Bose. As the ‘men of action’, both were known for their extremist viewpoints in their anti-colonial stance, and in sharp contrast with the philosophies of Nehru, whose idea of revolution, according to Madhavan Palat, was “non-violent”. This article by Singh, however, gives us a glimpse into a different strand of thought.

Singh begins by recounting the failure of Gandhi’s non-cooperation movement in bringing hope to the people of the nation. However, he goes on to admire the willingness of the youth of the country to take on the mantle of leadership and keep up the spirit of freedom alive.

“Many new leaders with a modern sensibility are emerging. Young leaders are at the forefront this time, and youth movements are proliferating. Only young leaders are commanding the attention of patriotic-minded Indians.”

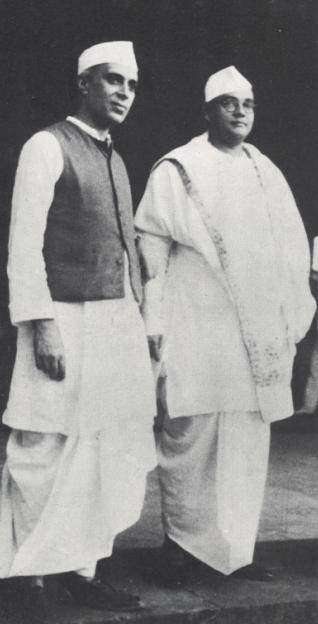

It is in this context that he pins down two emerging leaders, Subhash Chandra Bose and Jawaharlal Nehru, and goes on to describe them as “both uncompromising champions of Indian independence; both intelligent and genuine patriots”.

Krishna Bose also writes,

“When Bose and Nehru first appeared on India’s political scene in the early 20s, they appeared alike in many ways. Both emerged as leaders of youth and both had a magnetic charm about them. No other leaders of the time possessed this youthful charm which cast a spell on the nationalist masses… At the beginning of their political careers, the two strikingly handsome young leaders seemed to have a good deal in common. Their modernist orientation in politics and economics distinguished them from the deep-dyed Gandhians. Nehru and Bose shared a scientific approach towards India’s problems that was fundamentally opposed to the Gandhian creed of spinning our way to Swaraj and theories of non-industrialisation.”

How, then, history remembers the two leaders as having a different idea of a nation and freedom?

Before delving into their respective differences, Singh initially gives us an insight into another “champion of independence”, Sadhu Vaswani, the founder of Bharat Yuva Sangh, summing up his ideology in a single phrase: “Back to the Vedas”. Ironic as it may seem, Singh criticizes the very spirit of Vaswani that is associated with the identity of Singh himself in the popular discourse today. He says about Vaswani, “He’s a romantic poet. His poetry can offer no special purpose, it can only excite the heart a little. In fact, he has no vision to offer, except great noise about our ancient civilisation. He gives nothing to young minds. His only aim is to fill every heart with plain emotion. He has obvious influence among the youth, and it is growing. His ideas are regressive and patchy…”.

Coming back to Bose and Nehru, Singh then goes on to elaborate on the defining features of their personalities that separate the two. And to a reader’s surprise in today’s times, Singh appears to be critical of his revolutionary counterpart — Subhash Bose — envisioning, in contrast, Nehru’s idea of India.

“Pandit Ji wants to bring in revolution and change the existing system altogether. Subhash Chandra is emotional and romantic — he is giving the young food for their hearts, and only their hearts… Subhash Babu feels the need to focus on national politics only as long as it is necessary to safeguard and promote India’s position in world politics. But Pandit Ji has freed himself of the narrow confines of plain nationalism and emerged into an open field.”

“Which way should we incline?” — asks Singh, having held out his views about the two leaders and their thoughts. The answer, as is evident, is Nehru’s way. “Through serious thought and analysis, the youth should bring clarity and conviction to their ideas, so that even in times of very little hope, times of disillusionment and defeat, they should not lose direction, stand tall and strong against a hostile world and not give up. This is how the public will achieve the goal of revolution.”

Singh died three years after the publication of this article. The questions that linger on include the one that Apoorvanand asks here:

“What could have been his trajectory had he lived longer? Would he have joined Bose when the latter broke away from Gandhi and Nehru and went on to found Azad Hind Fauj and collaborated with Tojo and Hitler against the British?”

Read the full article as reproduced below.

After the failure of the non-cooperation movement, the Indian people had lost hope. Communal conflict between Hindus and Muslims wiped out the little resolve that still remained. But once a sense of awakening has come upon a nation, it cannot remain asleep for long. In just a few days, the public is back on its feet and ready for battle. Today, India is full of life and vigour again; it is awake. We may not see clear signs of a great mass movement, but the ground is certainly being prepared for it. Many new leaders with a modern sensibility are emerging. Young leaders are at the forefront this time, and youth movements are proliferating. Only young leaders are commanding the attention of patriotic-minded Indians. Even the tallest veteran leaders are being left behind.

Bhagat Singh

Many new leaders with a modern sensibility are emerging. Young leaders are at the forefront this time, and youth movements are proliferating. Only young leaders are commanding the attention of patriotic-minded Indians.

The leaders who have gained prominence this time are the venerable Subhash Chandra Bose of Bengal and the eminent Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru. These are the two leaders who appear to be rising above all others in India and involving themselves in youth movements in particular. They are both uncompromising champions of Indian independence; both intelligent and genuine patriots. And yet, their ideologies are as different as night and day. One is believed to be a devotee and proponent of India’s ancient culture and the other a committed follower of western civilization. If one is regarded as tender-hearted and sensitive, the other is spoken of as a quintessential revolutionary. Our attempt in this essay will be to present their respective ideologies before the public, so that people understand the difference between the two and make up their own minds.

But before we examine the ideas of these two leaders, it is important to mention another who is a champion of independence just as they are, and is also a prominent figure in certain youth movements. Sadhu Vaswani may not be as well known as the leading lights of the Congress, he may not occupy a special place in the country’s political arena, yet his influence is apparent among the youth, who will shape the country’s future. The organization Sadhu Vaswani founded — Bharat Yuva Sangh — has a particular hold on young Indians. Vaswani’s ideology can be summed up in a single phrase: back to the Vedas. This call was first given by the Arya Samaj. It is based on the belief that the Almighty has poured all the knowledge of the world into the Vedas. No progress is possible beyond them. Therefore, the world has not and cannot achieve anything greater than the wonders our very own India had achieved in the ancient past! So that is the entire faith of people like Vaswani. Which why he says:

“Up until now, our politics has either considered Mazzini and Voltaire as its ideals, or it has sought inspiration from Lenin and Tolstoy. This, when they should know that they have far greater ideals in our ancient rishis…”

Vaswani is convinced that once upon a time, our country had reached the final summit of development and today there is no reason for us to move forward at all; we only need to go back to the past.

Vaswani is a poet. Everything about his ideology is poetic. He is also a great practitioner of religious dharma. He wants to establish ‘Shakti-dharma’. He says, ‘At this time we need shakti — power — more than ever. He does not use the word ‘shakti’ only for India. He sees the word as the path and means to a kind of Devi, a special godhead. Like a very emotional poet he tells us:

‘For in solitude have I communicated with her, our admired Bharat Mata and my aching head has heard voices saying — “The day of freedom is not far off.” Sometimes indeed a strange feeling visits me and I say to myself: Holy, holy is Hindustan. For still is she under the protection of her mighty Rishis and their beauty is around us, but we behold it not.’

It must be the poet’s lament that makes him declare, over and over like a man deranged or distracted: ‘Our mother is the greatest. She is the mightiest. No one alive can vanquish her!’ In this fashion, driven purely by emotion, he ends up saying things like this: ‘Our national movement must become a purifying mass movement, if it is to fulfill its destiny without falling into class war one of the dangers of Bolshevism.’

He believes that all one needs to do is to say — ‘Go among the poor, go to the villages, give them free medicines’ — and our mission is accomplished. He’s a romantic poet. His poetry can offer no special purpose, it can only excite the heart a little. In fact, he has no vision to offer, except great noise about our ancient civilisation. He gives nothing to young minds. His only aim is to fill every heart with plain emotion. He has obvious influence among the youth, and it is growing. His ideas are regressive and patchy, as we’ve seen above. Such ideas have no direct connection with politics, and yet they have a significant effect. Mainly because it is the youth who are the future, and it is among them that such ideas are being propagated.

The leaders who have gained prominence this time are the venerable Subhash Chandra Bose of Bengal and the eminent Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru. These are the two leaders who appear to be rising above all others in India and involving themselves in youth movements in particular. They are both uncompromising champions of Indian independence; both intelligent and genuine patriots. And yet, their ideologies are as different as night and day.

Jawaharlal Nehru with Subhas Chandra Bose

Let us now return to Subhash Chandra Bose and Jawaharlal Nehru. During the last three months, they have both chaired many conferences and put their thoughts and ideas before people. The government considers Subhash Babu a member of the group that is committed to overthrowing it, for which reason it had charged and imprisoned him under the Bengal Act. Upon his release, he was chosen as the leader of the Extremist group [of the Congress]. He espouses Purna Swaraj [complete independence], and argued for this in his presidential address at the Maharashtra session [of the Congress].

Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru is the son of the Swaraj Party leader Motilal Nehru. He is a barrister, and a very learned man. He has travelled to Russia and other countries. He is also a leader of the Extremist group, and it was due to his efforts, and those of his fellow leaders, that the resolution for Purna Swaraj was passed and adopted at the Madras session. Before this, he had spoken emphatically in favour of Purna Swaraj at the Amritsar session.

And yet, the two leaders are poles apart in their thinking. Reading the transcripts of their speeches at the Amritsar and Maharashtra sessions, this difference was apparent to us. But the difference became clear as daylight after a speech delivered in Bombay. Pandit Nehru was chairing the conference and Subhash Bose made a speech. He is a very emotional Bengali. He began his address with the statement that India has a special message for the world. It has a lesson in spirituality for humanity. And then he launched into his speech like a man in the grip of disorienting emotion — ‘Behold the Taj Mahal on a moonlit night and think of the vision of that heart that imagined it. Recall that a Bengali novelist has written that “our flowing tears hardened into stone within us”. Bose also declares that we should return to the Vedas. In his Poona [Congress session] address, he had expounded on ‘nationalism’ and said that internationalists criticize nationalism as narrow, chauvinistic ideology, but that this is a mistake. Indian nationalist thought, according to him, is nothing of the kind. It is not chauvinistic. It is not born of self-interest, and it is not oppressive, because at its root is the philosophy of Satyam Shivam Sundaram — Truth is bountiful and beautiful.

The same old romanticism. Pure emotionalism. And [like Vaswani], Bose too has great faith in his ancient past. He sees only greatness in this ancient era. In his thinking, there’s nothing new in the system of panchayati raj, or the rule of the people, which he says is very old in India. He goes so far as to say that Communism isn’t new to India either. Anyway, that day in Bombay, he went on long and hard about India’s special message for the world.

Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru, like many others, holds an entirely different view: ‘Every country thinks it has a special message for the world. England has arrogated to itself the right to teach the world culture. I don’t see anything special that belongs to my country alone. But Subhash Babu has great belief in such things!’ Nehru also says, ‘Every youth must rebel. Not only in the political sphere, but in social, economic and religious spheres also. I have not much use for any man who comes and tells me that such and such thing is said in the Koran. Everything unreasonable must be discarded, even if they find authority for it in the Vedas and the Koran.’

One man thinks our old systems are very superior; the other man believes we should rebel against these systems. Yet the latter is called emotional, sensitive, and the former a transformative revolutionary!

These are the thoughts of a true revolutionary, while Subhash Chandra’s are the thoughts of someone who wants to replace one regime with another. One man thinks our old systems are very superior; the other man believes we should rebel against these systems. Yet the latter is called emotional, sensitive, and the former a transformative revolutionary! At one point Pandit Nehru says:

“To those who still fondly cherish old ideas and are starving to bring back the conditions which prevailed in Arabia 1300 years ago or in the vedic age in India, I say that it is inconceivable that you can bring back the hoary past. The world of reality will not retrace its steps, the world of imagination may remain stationary.”

This is why it feels necessary to revolt.

Jawaharlal Nehru and Subhash Chandra Bose

Subhash Babu supports Purna Swaraj, complete independence, because the British are people of the West and we are of the East. Pandit Ji’s position is that we need to establish our own rule so that we can change the entire social structure. This is why we must have complete and absolute independence.

Subhash Babu is in sympathy with labour, the working class, and wants to improve their condition. Pandit ji wants to bring in revolution and change the existing system altogether. Subhash Chandra is emotional and romantic — he is giving the young food for their hearts, and only their hearts. The other man is an epochal change — maker who is fuelling not just the heart but also the mind:

“They should aim at Swaraj for the masses based on Socialism. That was a revolutionary change which they could not bring about without revolutionary methods… Mere reform or gradual repairing of the existing machinery could not achieve the real, proper Swaraj for the general masses.”

Subhash Babu feels the need to focus on national politics only as long as it is necessary to safeguard and promote India’s position in world politics. But Pandit ji has freed himself of the narrow confines of plain nationalism and emerged into an open field.

Subhash Babu feels the need to focus on national politics only as long as it is necessary to safeguard and promote India’s position in world politics. But Pandit ji has freed himself of the narrow confines of plain nationalism and emerged into an open field.

Now the ideas of the [two] leaders are before us. Which way should we incline? One Punjabi newspaper has heaped praise upon Subhash Chandra and said of Pandit ji and others that such rebels destroy themselves beating their heads against stone. We must of course remember that Punjab has always been a rather emotional province. People’s passions here rise very quickly and just as quickly subside, like foam.

Subhash Chandra doesn’t appear to be providing any intellectual nourishment, only food for the heart. The need of the hour now is for the youth of Punjab to understand and strengthen revolutionary ideas. At this time, Punjab needs food for the mind, does not mean we should become his blind followers. But as far as ideas are concerned, the young people of Punjab should align themselves with him, so that they can know the true meaning of revolution, realize the need for a revolution in India, understand the significance of revolution in the world at large, and so on Through serious thought and analysis, the youth should bring clarity and conviction to their ideas, so that even in times of very little hope, times of disillusionment and defeat, they should not lose direction, stand tall and strong against a hostile world and not give up. This is how the public will achieve the goal of revolution.

— Bhagat Singh

This is a translation of Bhagat Singh’s ‘Naye Netaaon ke Alag Alag Vichar’ in the July 1928 issue of the journal Kirti. This translated version has been carried courtesy the permission of Purushottam Agrawal.

You can buy Who is Bharat Mata? On History, Culture and the Idea of India: Writings by and On Jawaharlal Nehru here.

Bhagat Singh (1907-1931), a socialist and a revolutionary, was executed by the British government in 1931, when he was just twenty-three. In 1928 Bhagat Singh plotted with others to kill the police chief responsible for the death of Indian writer and politician Lala Lajpat Rai, one of the founders of National College, during a silent march opposing the Simon Commission. Instead, in a case of mistaken identity, junior officer J.P. Saunders was killed, and Bhagat Singh had to flee Lahore to escape the death penalty. He worked as a writer and editor in Amritsar for Punjabi- and Urdu-language newspapers espousing Marxist theories. He is credited with popularizing the catchphrase “Inquilab zindabad” (“Long live the revolution”).

| 2500 BC - Present | |

|

2500 BC - Present |

| Tribal History: Looking for the Origins of the Kodavas | |

| 2200 BC to 600 AD | |

|

2200 BC to 600 AD |

| War, Political Violence and Rebellion in Ancient India | |

| 400 BC to 1001 AD | |

|

400 BC to 1001 AD |

| The Dissent of the ‘Nastika’ in Early India | |

| 600CE-1200CE | |

|

600CE-1200CE |

| The Other Side of the Vindhyas: An Alternative History of Power | |

| c. 700 - 1400 AD | |

|

c. 700 - 1400 AD |

| A Historian Recommends: Representing the ‘Other’ in Indian History | |

| c. 800 - 900 CE | |

|

c. 800 - 900 CE |

| ‘Drape me in his scent’: Female Sexuality and Devotion in Andal, the Goddess | |

| 1192 | |

|

1192 |

| Sufi Silsilahs: The Mystic Orders in India | |

| 1200 - 1850 | |

|

1200 - 1850 |

| Temples, deities, and the law. | |

| c. 1500 - 1600 AD | |

|

c. 1500 - 1600 AD |

| A Historian Recommends: Religion in Mughal India | |

| 1200-2020 | |

|

1200-2020 |

| Policing Untouchables and Producing Tamasha in Maharashtra | |

| 1530-1858 | |

|

1530-1858 |

| Rajputs, Mughals and the Handguns of Hindustan | |

| 1575 | |

|

1575 |

| Abdul Qadir Badauni & Abul Fazl: Two Mughal Intellectuals in King Akbar‘s Court | |

| 1579 | |

|

1579 |

| Padshah-i Islam | |

| 1550-1800 | |

|

1550-1800 |

| Who are the Bengal Muslims? : Conversion and Islamisation in Bengal | |

| c. 1600 CE-1900 CE | |

|

c. 1600 CE-1900 CE |

| The Birth of a Community: UP’s Ghazi Miyan and Narratives of ‘Conquest’ | |

| 1553 - 1900 | |

|

1553 - 1900 |

| What Happened to ‘Hindustan’? | |

| 1630-1680 | |

|

1630-1680 |

| Shivaji: Hindutva Icon or Secular Nationalist? | |

| 1630 -1680 | |

|

1630 -1680 |

| Shivaji: His Legacy & His Times | |

| c. 1724 – 1857 A.D. | |

|

c. 1724 – 1857 A.D. |

| Bahu Begum and the Gendered Struggle for Power | |

| 1818 - Present | |

|

1818 - Present |

| The Contesting Memories of Bhima-Koregaon | |

| 1831 | |

|

1831 |

| The Derozians’ India | |

| 1855 | |

|

1855 |

| Ayodhya 1855 | |

| 1856 | |

|

1856 |

| “Worshipping the dead is not an auspicious thing” — Ghalib | |

| 1857 | |

|

1857 |

| A Subaltern speaks: Dalit women’s counter-history of 1857 | |

| 1858 - 1976 | |

|

1858 - 1976 |

| Lifestyle as Resistance: The Curious Case of the Courtesans of Lucknow | |

| 1883 - 1894 | |

|

1883 - 1894 |

| The Sea Voyage Question: A Nineteenth century Debate | |

| 1887 | |

|

1887 |

| The Great Debaters: Tilak Vs. Agarkar | |

| 1893-1946 | |

|

1893-1946 |

| A Historian Recommends: Gandhi Vs. Caste | |

| 1897 | |

|

1897 |

| Queen Empress vs. Bal Gangadhar Tilak: An Autopsy | |

| 1913 - 1916 Modern Review | |

|

1913 - 1916 |

| A Young Ambedkar in New York | |

| 1916 | |

|

1916 |

| A Rare Account of World War I by an Indian Soldier | |

| 1917 | |

|

1917 |

| On Nationalism, by Tagore | |

| 1918 - 1919 | |

|

1918 - 1919 |

| What Happened to the Virus That Caused the World’s Deadliest Pandemic? | |

| 1920 - 1947 | |

|

1920 - 1947 |

| How One Should Celebrate Diwali, According to Gandhi | |

| 1921 | |

|

1921 |

| Great Debates: Tagore Vs. Gandhi (1921) | |

| 1921 - 2015 | |

|

1921 - 2015 |

| A History of Caste Politics and Elections in Bihar | |

| 1915-1921 | |

|

1915-1921 |

| The Satirical Genius of Gaganendranath Tagore | |

| 1924-1937 | |

|

1924-1937 |

| What were Gandhi’s Views on Religious Conversion? | |

| 1900-1950 | |

|

1900-1950 |

| Gazing at the Woman’s Body: Historicising Lust and Lechery in a Patriarchal Society | |

| 1925, 1926 | |

|

1925, 1926 |

| Great Debates: Tagore vs Gandhi (1925-1926) | |

| 1928 | |

|

1928 |

| Bhagat Singh’s dilemma: Nehru or Bose? | |

| 1930 Modern Review | |

|

1930 |

| The Modern Review Special: On the Nature of Reality | |

| 1932 | |

|

1932 |

| Caste, Gandhi and the Man Beside Gandhi | |

| 1933 - 1991 | |

|

1933 - 1991 |

| Raghubir Sinh: The Prince Who Would Be Historian | |

| 1935 | |

|

1935 |

| A Historian Recommends: SA Khan’s Timeless Presidential Address | |

| 1865-1928 | |

|

1865-1928 |

| Understanding Lajpat Rai’s Hindu Politics and Secularism | |

| 1935 Modern Review | |

|

1935 |

| The Modern Review Special: The Mind of a Judge | |

| 1936 Modern Review | |

|

1936 |

| The Modern Review Special: When Netaji Subhas Bose Was Wrongfully Detained for ‘Terrorism’ | |

| 1936 | |

|

1936 |

| Annihilation of Caste: Part 1 | |

| 1936 Modern Review | |

|

1936 |

| The Modern Review Special: An Indian MP in the British Parliament | |

| 1936 | |

|

1936 |

| Annihilation of Caste: Part 2 | |

| 1936 | |

|

1936 |

| A Reflection of His Age: Munshi Premchand on the True Purpose of Literature | |

| 1936 Modern Review | |

|

1936 |

| The Modern Review Special: The Defeat of a Dalit Candidate in a 1936 Municipal Election | |

| 1937 Modern Review | |

|

1937 |

| The Modern Review Special: Rashtrapati | |

| 1938 | |

|

1938 |

| Great Debates: Nehru Vs. Jinnah (1938) | |

| 1942 Modern Review | |

|

1942 |

| IHC Uncovers: A Parallel Government In British India (Part 1) | |

| 1943-1945 | |

|

1943-1945 |

| Origin Of The Azad Hind Fauj | |

| 1942-1945 | |

|

1942-1945 |

| IHC Uncovers: A Parallel Government in British India (Part 2) | |

| 1946 | |

|

1946 |

| Our Last War of Independence: The Royal Indian Navy Mutiny of 1946 | |

| 1946 | |

|

1946 |

| An Artist’s Account of the Tebhaga Movement in Pictures And Prose | |

| 1946 – 1947 | |

|

1946 – 1947 |

| “The Most Democratic People on Earth” : An Adivasi Voice in the Constituent Assembly | |

| 1946-1947 | |

|

1946-1947 |

| VP Menon and the Birth of Independent India | |

| 1916 - 1947 | |

|

1916 - 1947 |

| 8 @ 75: 8 Speeches Independent Indians Must Read | |

| 1947-1951 | |

|

1947-1951 |

| Ambedkar Cartoons: The Joke’s On Us | |

| 1948 | |

|

1948 |

| “My Father, Do Not Rest” | |

| 1940-1960 | |

|

1940-1960 |

| Integration Myth: A Silenced History of Hyderabad | |

| 1948 | |

|

1948 |

| The Assassination of a Mahatma, the Princely States and the ‘Hindu’ Nation | |

| 1949 | |

|

1949 |

| Ambedkar warns against India becoming a ‘Democracy in Form, Dictatorship in Fact’ | |

| 1950 | |

|

1950 |

| Illustrations from the constitution | |

| 1951 | |

|

1951 |

| How the First Amendment to the Indian Constitution Circumscribed Our Freedoms & How it was Passed | |

| 1967 | |

|

1967 |

| Once Upon A Time In Naxalbari | |

| 1970 | |

|

1970 |

| R.C. Majumdar on Shortcomings in Indian Historiography | |

| 1973 - 1993 | |

|

1973 - 1993 |

| Balasaheb Deoras: Kingmaker of the Sangh | |

| 1975 | |

|

1975 |

| The Emergency Package: Shadow Power | |

| 1975 | |

|

1975 |

| The Emergency Package: The Prehistory of Turkman Gate – Population Control | |

| 1977 – 2011 | |

|

1977 – 2011 |

| Power is an Unforgiving Mistress: Lessons from the Decline of the Left in Bengal | |

| 1984 | |

|

1984 |

| Mrs Gandhi’s Final Folly: Operation Blue Star | |

| 1916-2004 | |

|

1916-2004 |

| Amjad Ali Khan on M.S. Subbulakshmi: “A Glorious Chapter for Indian Classical Music” | |

| 2008 | |

|

2008 |

| Whose History Textbook Is It Anyway? | |

| 2006 - 2009 | |

|

2006 - 2009 |

| Singur-Nandigram-Lalgarh: Movements that Remade Mamata Banerjee | |

| 2020 | |

|

2020 |

| The Indo-China Conflict: 10 Books We Need To Read | |

| 2021 | |

|

2021 |

| Singing/Writing Liberation: Dalit Women’s Narratives | |

Thanks a lot for sharing this article. Kudos for the work you are doing. It is so necessary and important, at all times, but especially at a time like this when distortions and lies are propagated by charlatans hell bent on destroying our republic.

Wow! I am always blown away by Bhagat Singh. He was so astute and wrote with such clarity despite his youth. Thank you for sharing !