The role of women in history, especially in the pre-modern period, is not considered to be of particular importance with respect to macro-level political, social or economic events. This is due in part to the restrictions placed upon the mobility (such as the custom of purdah) of elite women, significantly limiting their public presence, and partially because of the biases of contemporary chroniclers which leave us with far fewer sources to reconstruct the lives of women as compared to male rulers. There are some notable exceptions to this phenomenon – Razia Sultan is celebrated as the first female Muslim ruler of the Indian subcontinent and Jahanara Begum, the daughter of Shah Jahan, is credited with a significant role in the building of the city of Shahjahanabad (Old Delhi).

However, there were many other women, who had a great impact on the history of the country without occupying such a public position or leaving physical imprints of the same. The wives of male rulers, particularly, could exercise considerable influence in politics despite operating as they did from within the confines of the zenana or harem. A notable example of such women were the Begums of Awadh, whose role in the history of the kingdom spanned nearly its entire existence, i.e. 135 years.

While, as KS Santha writes, the atmosphere of the harem could “be considered extremely unlikely as fostering ground for women of high calibre who could leave their mark on the history of the kingdom,” a close study of the documentary evidence of the period leads her to conclude that “had these courageous Begums been aided instead of hindered by circumstances, they may have easily found their place amongst the ablest.” This excerpt from KS Santha’s book, The Begums of Awadh, published in 1980, looks at the life of Bahu Begum, the wife of Nawab Mirza Jalal-ud-din Haidar Shuja-ud-daulah.

The roots of the “dynastic history” of Awadh can be traced to the appointment of Mir Muhammad Amin Saadat Khan Burhan-ul-mulk as Governor of the Mughal province in 1722 A.D. By this time, the power of the Mughal Emperors had begun to wane. While they were still the nominal rulers, their feudatories had begun to exercise considerable power of their own. This was the situation that confronted Saadat Khan when he arrived in Awadh, which was “dominated by semi-independent feudal barons.”

The story of how he was able to subdue these feudal lords and establish his control over the province is one coloured by much political manoeuvring, intrigues and negotiations, which may not detain us here. What is relevant is that by the time of his death, he had established a hold over the kingdom of Awadh such that it passed into the hands of Safdar Jung, his son-in-law and husband of the first influential Begum of Awadh, Sadr-i-Jahan. Thus, as Santha states, “very early in the history of Awadh the impress of the first Begum left its mark.” Safdar Jung was also appointed the Wazir to the Mughal Emperor and it was on imperial behest that their son, Shuja-ud-daulah, third Nawab of Awadh, was married to Bahu Begum in 1745 A.D.

Before moving on to the life of Bahu Begum, however, it is important to highlight another aspect of the history of Awadh – that of the growing power of the East India Company. The Company had already established footholds in parts of the Indian Subcontinent by the first half of the 18th century but their power increased significantly after the Battle of Plassey (1757), through which they got control of Bengal, and the Battle of Buxar (1764). Shuja-ud-daulah had entered the Battle of Buxar in support of the losing side and therefore had to sign the Treaty of Allahabad, concluded in 1765, which was ruinous to the state. His successor, Asaf-ud-daulah, further signed the Treaty of Benares (1778), ceding significant territory to the Company, and the Treaty of Chunar (1781).

The life and politics of Bahu Begum must be placed in the above context. She was keenly aware of the political realities of the period and tried her best to preserve the independence of Awadh. For instance, she remained bitterly opposed to the Treaty of Benares, even if it earned her the displeasure of Company authorities. At the same time, she was a shrewd woman who did not hesitate from appealing to these very authorities when it came to protecting her interests and those of her people.

Born as Umat-ul-Zohra Begum, she was the daughter of Motamn-ud-daulah Nawab Muhammad Ishaq Khan, the Governor of Gujarat. Her family had a long history of imperial service and both her father and brother were important pillars of support for the Emperor. Such was his indebtedness to her family, that Bahu Begum became his adoptive daughter and her marriage was arranged to Shuja-ud-daulah on his request. While initially she was deprived of the affection of her husband, her support to him after his defeat in the Battle of Buxar, when he had been abandoned by many near and dear ones, succeeded in creating a place for her in his heart. She became the chief consort of the Nawab, who showered her with gifts and also fifty percent of the revenues of the state. Due to “such grateful gestures from her husband,” she “amassed great wealth besides the ownership of the jagirs that were bestowed upon her.”

She was an efficient administrator, despite the limits placed upon her mobility due to the practice of purdah. She governed her jagirs through a hierarchy of officials, with many of whom she built strong ties of trust through her generosity. After her son, Asaf-ud-daulah, shifted the capital to Lucknow, she “practically governed Faizabad.”

Tragically, after the death of Shuja-ud-daulah, she entered into a protracted conflict with her son, Asaf-ud-daulah and two of his ministers, Murtaza Khan and Haidar Beg Khan. According to KS Santha, Asaf-ud-daulah was a weak-willed ruler who was easily influenced by his ministers. He frequently appealed to his mother for a share of her wealth and their relationship suffered as a consequence of her refusal. Bahu Begum reached out to British Resident for assistance and later, perhaps breaching the bounds of ‘propriety,’ even wrote to the Governor-General. However, the Company refused to help her as they benefited more from supporting the Nawab, who promised them huge payments from the wealth he would acquire from his mother.

Further, the Company was suspicious of the Begum’s hostility towards their increasing power in Awadh – she was even accused of being one of the chief conspirators, along with Sadr-i-Jahan, in the rebellion of Chait Singh in 1781. As a consequence of the machinations of the ministers of the Nawab and the hostility of the Company, she lost many of her jagirs and much of her wealth. However, she continued to be an influential figure in politics and was a main party in the conflict surrounding the ascension of Wazir Ali and later, Saadat Ali Khan, to the masnad after the death of Asaf-ud-daulah. She strongly opposed Saadat Ali Khan’s ascension since she feared he was under the thumb of the British, which later proved to be true, but she was not successful in installing his brother, Mirza Jungli, upon the throne instead.

The story of Bahu Begum may not come across as one of success, since she had to deal with many losses and betrayals. However, it does much to illuminate the administrative abilities, shrewdness and knowledge of statecraft that the Begums of Awadh possessed. Though she arguably had much greater political acumen than the Nawabs and could predict the future decline of Awadh under the British, her advice was often ignored.

Despite the losses she suffered, it must be remembered that she had to contend with the combined power of the Nawab of Awadh and the East India Company, and yet was able to safeguard her dignity, position and influence, if not her wealth. She outlived both Asaf-ud-daulah and Saadat Ali Khan and was remembered by the chroniclers of the age for her efficiency, generosity and grace. Bahu Begum’s legacy was carried forward by Begums who came after her, most notably, Begum Hazrat Mahal, the wife of exiled Nawab Wajid Ali Shah, who mobilised large sections of Awadh during the Revolt of 1857.

Bahu Begum was the most significant and renowned of the Begums of Awadh who left a significant mark in Indian History. Her real name was Umat-ul-Zohra Begum. She was the daughter of Motamn-ud-daulah Nawab Muhammad Ishaq Khan who was the great-grandson of Mirza Soshthari and belonged to the lineage of Malik Asther. He was the Governor of Gujrat. Her grand-father had been in the employment of Aurangzeb. Motamn-ud-daulah Muhammad Ishaq Khan was [the] great Iranian leader of the Mughal court and had held the post of Diwan-i-Khas. His death deprived the emperor of a great supporter against the powerful Turani party led by Nizam-ul-mulk. While, the conduct of another Iranian leader, Amir Khan Umdat-ul-mulk was unendurable to the Emperor, he decided to raise Mirza Muhammad Khan Najm-ud-daulah, who was his favourite and the son of Ishaq Khan, to a high rank equal to that of Amir Khan. He called Safdar Jung, the then Prime Minister (Wazir-i-Azam) to negotiate for the marriage between Jalal-ud-din Haidar Shuja-ud-daulah and the sister of Najm-ud-daulah, the future Bahu Begum. The Emperor declared her to be his daughter and deputed Amir Khan to make preparations for her marriage. Safdar Jung was extremely pleased with this proposal. Desirous like-wise of complimenting the Imperial pleasure, “he exerted himself in rendering the nuptials as pompous and as magnificent as possible.” Among other articles which Safdar Jung has sent as usual to the bride, as part of her future dowry, were hundreds of silver vessels, “each one of which weighed not less than one hundred rupees or hundred tolas.” The procession of gift bearers accompanied by friends and well-wishers with gifts to the bride on the sachek (Bridegroom’s gifts to the bride) extended from the foot to Kotila Feroz. Nothing could be seen but the trays full of various kinds of sweets, fruits, apparel, ornaments, bottles of perfumes and a large number of vessels of various shapes, designs and workmanship. The bride’s party too sent in return, presents on the Mehndi which were even costlier than those of sachek. The marriage was performed amidst great feasting and illumination. The expenditure was supposed to be to the tune of forty-six lakhs of rupees. The great ceremony took place in 1158H, July/August, 1745 A.D. It was said that none had witnessed such a marriage which was equal to that of Jafar Khan, the Wazir of Shah Jahan or that of Emperor Farrukh Siyar.

Bahu Begum of Awadh.

Bahu Begum, the much favoured foster child of the Mughal Emperor, was married to Shuja-ud-daulah primarily for the sake of political expediency and so did not seem to have appealed to her libertine husband. Bahu Begum came to Awadh with a fabulous dowry and added prestige to the family of Safdar Jung. Although illiterate, she undoubtedly possessed great abilities and a shrewd mind. She had heard and also witnessed the changes of fortune from the days of Bahadur Shah I to Shah Alam and was well acquainted with the intrigues of the Mughal Court. She exhibited a remarkable alertness whenever occasion demanded. At the same time, she was a kind and an affectionate woman and treated her relatives very cordially. She was deeply attached to two of her brothers Mirza Ali Khan and Salar Jung who were with her at Faizabad.

Although illiterate, she undoubtedly possessed great abilities and a shrewd mind. She had heard and also witnessed the changes of fortune from the days of Bahadur Shah I to Shah Alam and was well acquainted with the intrigues of the Mughal Court. She exhibited a remarkable alertness whenever occasion demanded. At the same time, she was a kind and an affectionate woman and treated her relatives very cordially.

In the time of Bahu Begum the English had acquitted [acquired?] greater power and consequence in Awadh. They did not as yet allow the semblance of friendly relationship to be affected by their assumption of superiority. Bahu Begum, being a gracious princess, was very hospitable towards the English residents, travellers and authorities. Lord Valentia, Hodges and others visited the Begum, and testified to her hospitality. If English officers were to pass through Faizabad, her orders were that people of the city should render them assistance and that her agents should look after their needs.

Shuja-ud-daulah, Third Nawab of Awadh.

At the time of the debacle of Buxar, Shuja-ud-daulah was defeated and humiliated and was the mercy of the English for the restoration of his position. Bahu Begum revealed her magnanimous nature which was a turning point in the relations of Shuja-ud-daulah towards his wife. He had appealed to his mother, wife, relations, friends and other important officials for help in cash, jewels, and other precious articles. Most of the persons evaded the full compliance and sent only a quarter or half of what they could spare. Despite the warnings of her own kith and kin, Bahu Begum gave away everything that she possessed including even her nose ring, with its bunch of pearls which no married woman would ordinarily part with under the direst conditions. She silenced her advisers by saying “whatever I have is of use to me, so long as Shuja-ud-daulah is safe. If he ceases to live, all these things would also cease to be of value to me.”

The author of Sier-ul-Mutakhirin, in that context wrote that “It was only a woman that spoke so; but her sentiments would have done honour to any man upon earth. And may so much generosity and so much gratitude, may so respectable a remembrance of scoeity, of table and bed be ever rewarded with the blessing of heaven. Doubtless it is of such [a] noble minded woman, that the poet thought when he said “A pious, obedient and dutiful woman will make a king of a poor man.”

Shuja-ud-daulah was touched by her devotion and noble disposition and thereafter held her in high esteem. He treated her with respect and affection. In spite of his unbridled licentiousness that continued throughout his life, he paid great attention to his wife and made it a custom to dine both times of the day at her palace. After his mid-day rest, at about 2 O’clock, he used to pay stealthy visits to his other women. Bahu Begum, however, knew about the visits, because she used to call her husband a thief and the palaces belonging to the secondary wives as chor mahal. He invariably passed the nights in the palace of Bahu Begum and when he failed to do so, he would pay the Begum Rs. 5000/- as the stipulated fine for his nocturnal misbehaviour.

Shuja-ud-daulah had also made it customary, as a grateful gesture to Bahu Begum to commit to her care whatever money came to his hands in presents or could be spared from necessary expenses. He daily used to examine the balance sheet prepared by Diwan Surat Singh and order Illich Khan and Muhammad Bashir Khan to realise the same from the district officials and Collectors and deposit the same into the Nawab’s private until he returned home at midday. After examining the account, he would order that half of the amount should be handed over to Bahu Begum. As a consequence of such grateful gestures from her husband, the Begum amassed great wealth besides the ownership of the jagirs that were bestowed upon her.

Shuja-ud-daulah had also made it customary, as a grateful gesture to Bahu Begum to commit to her care whatever money came to his hands in presents or could be spared from necessary expenses… After examining the account, he would order that half of the amount should be handed over to Bahu Begum. As a consequence of such grateful gestures from her husband, the Begum amassed great wealth besides the ownership of the jagirs that were bestowed upon her.

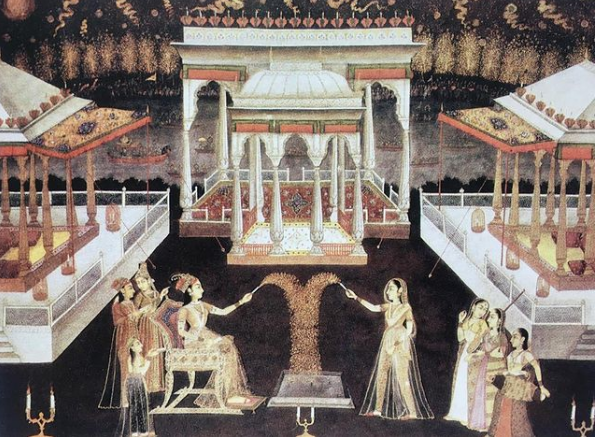

In this 1750 painting of the festival of Shab-e Barat, it is possibly Bahu Begum shown sitting on a jewelled throne of gold, lighting fireworks in her summer pavilion with her friends. (Image credit: Vijay Sharma, paintings in the Kangra Valley. From Ira Mukhoty’s Instagram)

Thus, she gained the confidence of her husband and could later on share in his official dealings. She accompanied Shuja-ud-daulah to Banaras when it was rumoured that Warren Hastings was to arrive at Banaras, who was entertaining misgivings about Shuja-ud-daulah’s interest in increasing the army and maintaining friendly relations with other countries. Obviously Shuja-ud-daulah was nervous of the forthcoming encounter with Hastings and probably Bahu Begum went with him to render moral support.

As the chief consort to Shuja-ud-daulah, she held a distinguished position in the harem. None ventured to mention to her the names of Shuja-ud-daulah’s inferior wives. Only after the Nawab’s death, these women gradually made her acquaintance and Mirza Mangli (the future Yamini-ud-daulah Saadat Ali Khan) and Mirza Jangli were sometimes admitted to see her. Many years later, the inferior wives could address her and it was said that they were like slave girls to her. After his death they begged her to permit them to accompany her when she took a stroll in the gardens and visited such other places. She hired bullock coaches in which they could accompany her. Yet they were never permitted to sit before her. Only a few who were more respectable were allowed to sit behind her and that too beyond her carpet. The imperious lady was upset when Saadat Ali Khan, after his accession called his own mother to Lucknow and conferred distinctions upon her equal to that of Bahu Begum. Bahu Begum did not allow Saadat Ali Khan’s mother and her retinue to pass through her residence at Brij Tilai.

Bahu Begum, however, was concerned about their comfortable living. She complained to the Company authorities about the pensions left by Shuja-ud-daulah to his inferior wives and others, who were in dire distress as they had difficulties in obtaining the cash amount. She, therefore, requested the company to assign the district of Gonda to her so as to enable her to pay these persons every month. The company acceded to her request.

She continued to maintain her dignity and rank after the death of Shuja-ud-daulah by observing the customary formalities of pomp and show. Her private life was marked by sadness and austerity. She took only one meal per day and slept on a bare ebony bed. She regularly observed the anniversary of her husband’s death and liberally provided for the maintenance of the tomb of Shuja-ud-daulah with carpets, illuminations and recitation of Koran at the tomb. Her love for her husband was intense and she cherished his memory fondly. She was supposed to have said a day before her death that Nawab Shuja-ud-daulah had come to take her.

She continued to maintain her dignity and rank after the death of Shuja-ud-daulah by observing the customary formalities of pomp and show. Her private life was marked by sadness and austerity. She took only one meal per day and slept on a bare ebony bed. She regularly observed the anniversary of her husband’s death and liberally provided for the maintenance of the tomb of Shuja-ud-daulah with carpets, illuminations and recitation of Koran at the tomb. Her love for her husband was intense and she cherished his memory fondly. She was supposed to have said a day before her death that Nawab Shuja-ud-daula had come to take her.

A bathing scene from the zenana. Awadh, 1760 – 1777.

Bahu Begum was extremely fond of her only son Asaf-ud-daulah whom she pampered excessively. Perhaps this proved injurious to Asaf-ud-daulah’s up-bringing. Shuja-ud-daulah himself brought up strictly by his parents, disapproved of his son’s actions and was greatly incensed with his behaviour. On one occasion Bahu Begum intervened to save her son from being nearly killed by his father.

Asaf-ud-daulah his not prove to be a promising son. He began to take interest in and indulge in such acts that were very disappointing and disgusting to his teachers as well as his father. The father doubted the abilities of his heir and began to entertain the idea of nomination Mirza Mangli (the future Saadat Ali Khan) as his successor. Mirza Mangli was intelligent, shrewd and took a keen interest in matters of administration and organisation of the state. Bahu Begum’s blind affection for her only son led her to disregard her husband’s wishes as well as the wise suggestions of Sadr-i-Jahan Begum who also warned her against Asaf-ud-daulah. Had Bahu Begum taken the advice of Sadr-i-Jahan Begum, perhaps the subsequent poignant events could at least have been averted. Though shrewd and intelligent, she was swayed by motherly love. Later events made the relationship between the kind mother and her son painful, each event piling fresh distress upon her.

Asaf-ud-daulah proved true to the observations of his grand-mother. Immediately after the death of Shuja-ud-daulah, he proceeded to Mehdi Ghat for an excursion and instigated by his companion and minister Murtaza Khan Mukhtar-ud-daulah, applied to his mother for expenses. Murtaza Khan approached her for money. Bahu Begum’s brother Salar Jung mediated for this purpose. She expressed grief at Asaf-ud-daulah’s lack of respect for his father who was hardly dead ten days. She was distressed at the untimely demand for money while she was still in mourning. She asked Salar Jung whether Asaf-ud-daulah had no time to shed a tear for his father. In the end the indulgent mother yielded after two or three days of negotiations and gave him six lakhs of rupees. As predicted, this proved to be the first occasion of a breach between the mother and the son. The money was frittered away by Asaf-ud-daulah within a very short time and he repeated the demand, through another mediator called Mirza Ali Khan who was also her brother.

(She had three brothers – Najm-ud-daulah, Mirza Ali Khan and Salar Jung, see Imad-us-Saadat, p. 35)

Bahu Begum was greatly displeased but gave him again four lakhs of rupees. As the sum was too small, Asaf-ud-daulah hurried back to Faizabad and asked for more money on loan. He gave her a sanad directing Naoroz Ali Khan to make over certain mahals etc. out of his districts to her against the loan of four lakhs of rupees. He also promises that he would not make any further demands. Asaf-ud-daulah never returned to Faizabad. He proceeded to Lucknow and permanently took up his residence at the Yakh Mahal.

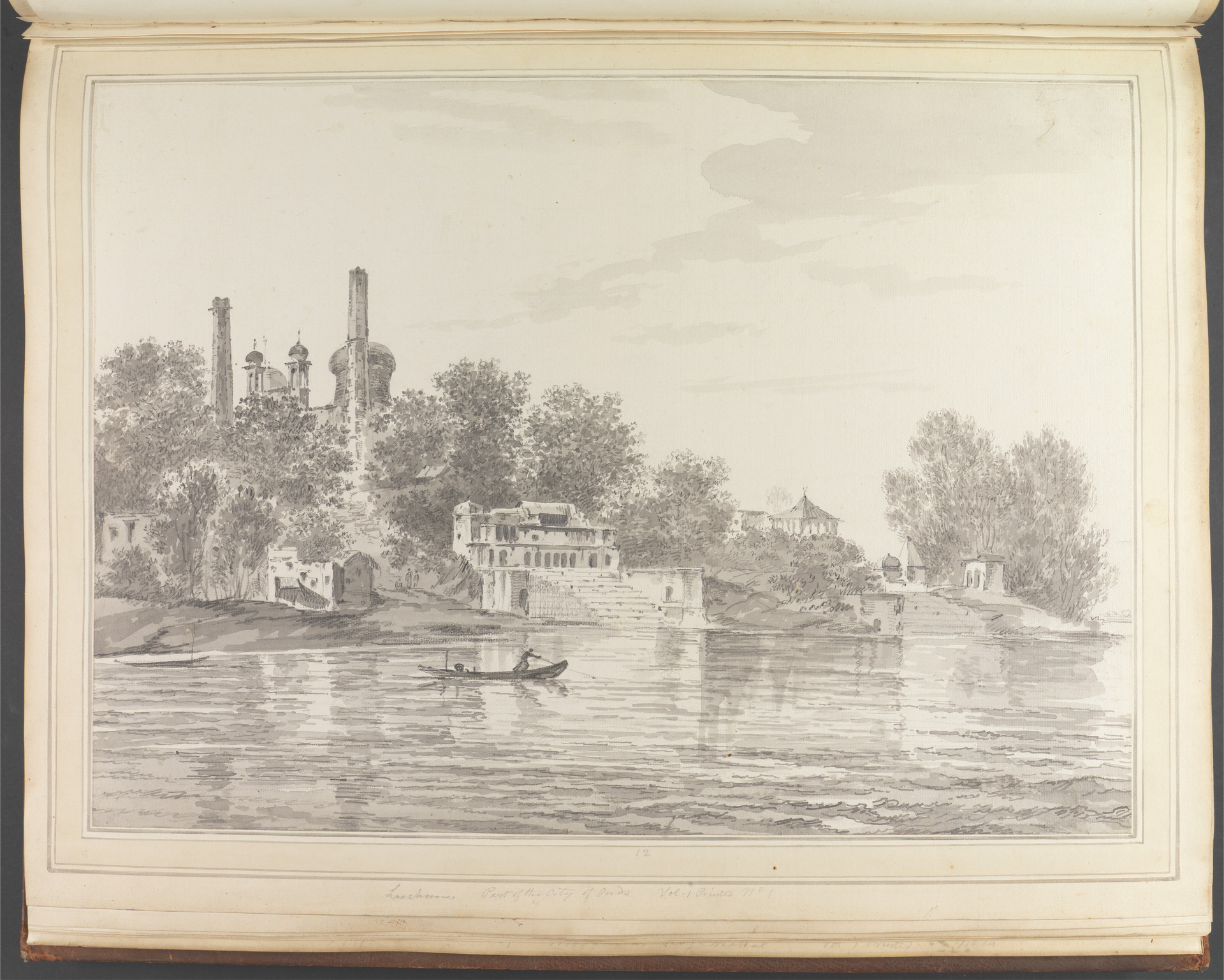

A painting by William Hodges, titled “A View of Part of the City of Oudh,” c. 1783.

It is said that this move was manoeuvred by Murtaza Khan. Murtaza Khan was the same man who with his brother had been banished from Awadh by Shuja-ud-daulah for their father’s aspersions against Sadr-i-Jahan Begum. These two brothers had returned to Lucknow and had managed to gain the favour of Asaf-ud-daulah much to the anger and displeasure of Shuja-ud-daulah. After the death of Shuja-ud-daulah, their elevation in the court of Faizabad has merited warnings from Sadr-i-Jahan Begum. They, however, continued to flourish.

Immediately after the death of Shuja-ud-daulah, he [Asaf-ud-daulah] proceeded to Mehdi Ghat for an excursion and instigated by his companion and minister Murtaza Khan Mukhtar-ud-daulah, applied to his mother for expenses. Murtaza Khan approached her for money. Bahu Begum’s brother Salar Jung mediated for this purpose. She expressed grief at Asaf-ud-daulah’s lack of respect for his father who was hardly dead ten days…In the end the indulgent mother yielded after two or three days of negotiations and gave him six lakhs of rupees.

Murtaza Khan, fearing the interference and influence of the two Begums in the activities of Asaf-ud-daulah, cleverly instigated the plan of separating him from them. Asaf-ud-daulah was too simple and weak to grasp such intricate moves and was contented by the very idea of his pursuing a leisurely life of amusement unhampered and unchecked by the strict Begums. He easily fell into the trap and proceeded to Lucknow. At Lucknow, he completely abandoned his interest in the Government and became deeply engrossed in wine and unworthy activities. The mantle of protection, advice and maternal care were thus removed from him permanently. This was ruinous for him and the state in general.

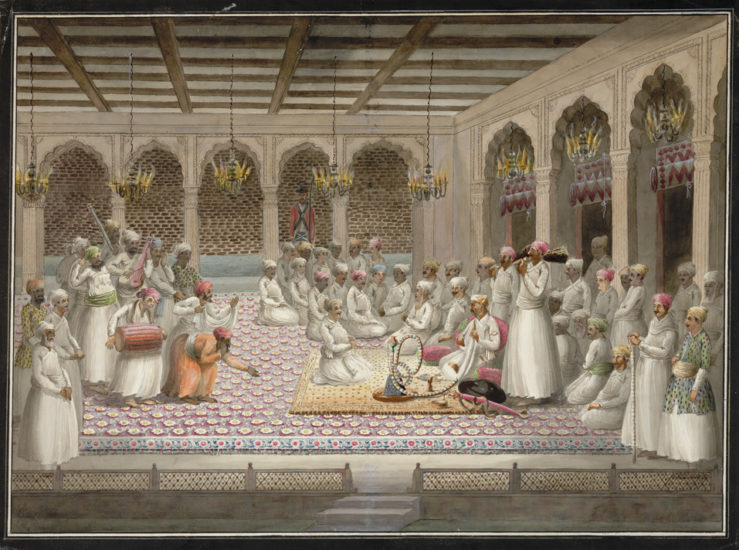

Asaf-ud-daulah listening to musicians in his court and smoking a hookah, c. 1812.

It is believed that Murtaza Khan had been nursing a deep grudge against the family of Shuja-ud-daulah and had intended to bring ruin to that house. He slowly undertook to impair the government and appoint his own men in various offices. He appointed his brother Saiyyad Muhammad Khan as his deputy and sent him to Faizabad where he behaved disrespectfully and without courtesy to the Begums (Saiyyad Muhammad Khan began to order the drums to be beaten as a mark of his office whenever he rode through chowk where the two respected Begums resided at Moti Mahal which was a slight to the Begums. Memoirs of Delhi and Faizabad, Vol. II, p. 24). He also appointed his own men in the various offices and began to dismiss the trusted old servants of Shuja-ud-daulah. Unfortunately, the two brothers of Bahu Begum who were at Faizabad remained docile due to “their personal cowardice and profligate pursuits.” They even gave a daughter’s hand in marriage to the son of Murtaza Khan.

The growing influence of Murtaza Khan made Bahu Begum feel insecure. She preferred to contact the officials of the East India Company directly and intended to secure their sympathy and support if possible. She therefore addressed a formal letter to the Resident of Awadh, John Bristow who had just reached Lucknow. She expressed in her letter that she wished to go to Karbala and to deposit the remains of her husband at that place. The letter was a mere pretext to communicate with the Resident or might have been an expression of sheer disgust at the behaviour of her son. Whatever it might be, the Resident immediately reciprocated, and expressed concern at her plans. He wrote to the Governor-General about it and some correspondence relating to the arrangements for her journey took place.

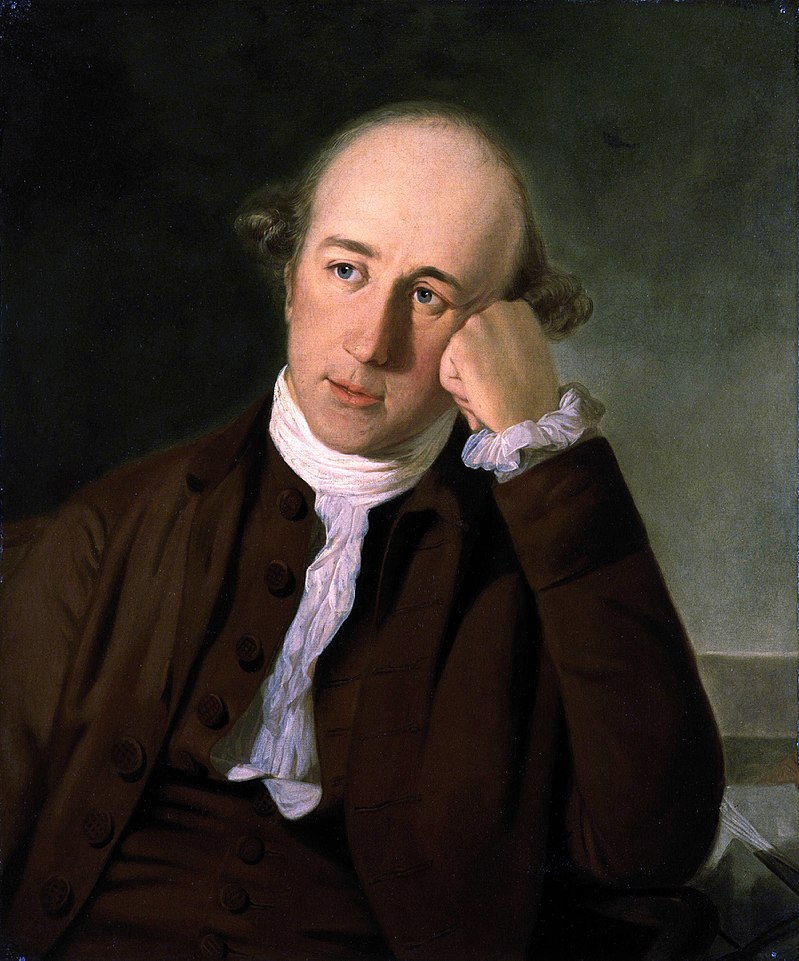

Awadh British Resident John Bristow’s successor Nathaniel Middleton.

The Nawab under the influence of the minister Murtaza Khan reacted to such direct dealings between the Begum and the Resident. In a polished manner, he indicated to the Resident that it was not his desire to break the correspondence. On the other hand he only wished “to have the custom of his country and Hindostan adhered to and not to see the Begum supplying a connection independently to him.”

The growing influence of [Minister] Murtaza Khan made Bahu Begum feel insecure. She preferred to contact the officials of the East India Company directly and intended to secure their sympathy and support if possible. She therefore addressed a formal letter to the Resident of Awadh, John Bristow who had just reached Lucknow. She expressed in her letter that she wished to go to Karbala and to deposit the remains of her husband at that place…the Resident immediately reciprocated, and expressed concern at her plans.

Meanwhile the Begum sent another letter in which she boldly complained that her son was displeased with her and had threatened to take away the life of her principal agent and to dishonour and disgrace her. She, therefore, requested the Resident to visit her immediately. The shrewd Resident sensed the situation and understood that she expected him to become a party in this dispute and support her. The attitude of the Resident now became more sympathetic towards the Nawab, since he learnt about the large fortune that was in the possession of the Begum and the desire of the Nawab to receive a substantial amount from it on the basis of the Muhammadan law. The Nawab desired that amount so as to repay the arrears which he owed the Company for the cost of maintaining a brigade. Henceforth the Resident became unsympathetic to her; this change is clearly noticeable in this entire correspondence with the Governor-General, as well as in the Begum’s letters to the Governor-General in which she complained about the Resident’s attitude.

When such imperceptible and forceful motives were acting silently, Murtaza Khan added colour to them. He resolved to go to Faizabad and ruin the Begum financially. He knew that vast treasures were lying hidden in Bahu Begum’s palace. He cleverly persuaded Asaf-ud-daulah while he was intoxicated saying, “All the accumulated wealth of Safdar Jung and Shuja-ud-daulah is with the Begum, and it will all go to keep up the style of their eunuchs. If you direct, I shall go and get it out of them as best as I can.” Asaf-ud-daulah gave into his malicious persuasions. Once again Bahu Begum was approached by Murtaza Khan, accompanied by the English Resident, John Bristow. A huge force was taken with the eunuch Brigadier Basant Ali Khan and Salar Jung. Murtaza Khan’s mode of behaviour had changed to rudeness by now. Feelings ran high, creating a tense situation for a few days. Mirza Ali Khan made Bahu Begum accept the proposal of Bristow to give enough money, assuring her that Asaf-ud-daulah would not trouble her in the future and that Bristow would stand as a guarantor of a written agreement by Asaf-ud-daulah to abide by his promise. The helpless lady agreed and paid 30 lakhs of rupees in cash and in kind as follows:

All the articles were taken to Lucknow and were undervalued by Murtaza Khan through his Bankers. He made allegations that the articles, such as elephants, camels etc. worth rupees eleven lakhs, actually belonged to Asaf-ud-daulah’s Government and, therefore, were not be considered as part of the thirty lakhs of rupees. Bahu Begum was asked to pay an extra amount of eleven lakhs.

Asaf-ud-Daulah’s Palace, Lucknow.

Once again Bahu Begum was approached by Murtaza Khan, accompanied by the English Resident, John Bristow. A huge force was taken with the eunuch Brigadier Basant Ali Khan and Salar Jung. Murtaza Khan’s mode of behaviour had changed to rudeness by now. Feelings ran high, creating a tense situation for a few days. Mirza Ali Khan made Bahu Begum accept the proposal of Bristow to give enough money, assuring her that Asaf-ud-daulah would not trouble her in the future and that Bristow would stand as a guarantor of a written agreement by Asaf-ud-daulah to abide by his promise.

The Begum then wrote to the Governor-General about it. (Bahu Begum in this letter justified her direct approach to the Governor-General by writing “I went to the Nabab where the hour of his death approached and asked him to whose charge he left me; he replied “Apply to Mr. Hastings whenever you have occasion for assistance, he will befriend you when I am no more and will comply with whatever you may desire of him”). In the letter she bitterly complained about her son and the mischief of Murtaza Khan. She elaborately wrote that her articles which she had given as a part of 30 lakhs of rupees to the Nawab were deliberately under-estimated by the Bankers of Murtaza Khan. She also complained about Bristow’s indifferent behaviour and charged him directly with having “sent a message to her in his own name that he would stop her provisions, beat her servants and send people to plunder the Zanana.” She expressed in the same letter her willingness to proceed to some such place as Banaras or Azimabad (Patna) where she could live peacefully and unmolested by the Nawab. The Governor-General then, while demanding an explanation from Bristow, directed him to get the articles appraised by such persons who would be agreeable to both parties. He wrote that the authorities were willing to grant her a suitable retreat, provided she could obtain the Nawab’s consent. Bristow replied to the Governor-General denying his misconduct towards the Begum and justified his action. He also tried to impress upon the Governor-General the futility of extending sympathy to a person of Bahu Begum who had opposed the treaty of Faizabad (1775) in which Banaras was to be given to the Company by Asaf-ud-daulah.

This culminated in the final estrangement of the relationship between the mother and the son. Thereafter, she never mentioned his name and turned her head away, if anyone else mentioned it. Whenever she was compelled to write to him, she wrote on the envelope merely ‘Asaf-ud-daulah’ instead of using the endearing term “Burkhurdar Nur Chashm.” Yet another disgraceful act was committed by him as reward to all her maternal affection. (see next chapter)

Governor-General Warren Hastings, 1772 – 1785.

Seven years passed in this manner from the time he sat on the masnad. Whenever he passed through Faizabad, he halted for a night or two and then formally called on his mother. He sat in her presence for a few minutes and left. There was no warmth or cordiality on either side. Later, when Warren Hastings suggested to Asaf-ud-daulah to have reconciliation with his mother, he visited her and returned her jagirs and tried to appease her and the old Begum, his grand-mother, by taking them to Lucknow and showering all courtesies upon them and tried to make up for the previous ill inflicted on them. The loving mother forgave him and went him to Bitul for an excursion. Besides this, when she arranged the marriage of her nephew, Asaf-ud-daulah readily came to Faizabad and stayed at her palace until the marriage ceremony was completed.

Later, when Warren Hastings suggested to Asaf-ud-daulah to have reconciliation with his mother, he visited her and returned her jagirs and tried to appease her and the old Begum, his grand-mother, by taking them to Lucknow and showering all courtesies upon them and tried to make up for the previous ill inflicted on them. The loving mother forgave him and went him to Bitul for an excursion.

Asaf-ud-daulah inspite of all his dishonourable acts, loved his mother. When he became seriously ill and knew that he was going to die, he remained brave and poised before all. But when Bahu Begum came to him he could no longer bear and both mother and son silently wept for hours.

However, she outlived him for twenty years and died on Thursday, the 26th Muharram, 1230H (1815 A.D.) at about 2 O’clock in the afternoon amidst tears and cries of her aged and sorrowing servants. None of her dear and near ones had survived except her steward Darab Ali Khan who had succeeded Jawahar Ali Khan. A mention, however, about her wealth and entire establishment may not be out of place.

Bahu Begum lived a life of style and form. Her residence Moti Mahal was situated in the fort. “The walls of the Moti Mahal were very high and of more than twelve cubics.” Outside, right against the walls on all four sides there were lines of houses occupied by the Mewatis’ infantry which guarded the Mahal night and day. Besides, fifty Mewatis under the command of a subaltern used to the walk round the palace throughout the night playing cymbals. At the door of the Begum’s harem, there was at the first entrances a regular infantry, at the second entrance Baheliya infantry and at the third near the inner door there were messengers who were employed to bring supplies from the Bazar. With them were chelas and beadles who carried silver maces. Beyond them and inside the inner door there were Kashmiri women, big and fat who were even better than men for the purpose of vigilance. Beyond was a door which used to be locked both inside and outside. Inside the seraglio and the locked door about twenty five eunuchs both old and young were on guard. In Bahu Begum’s private bed room four smart Mughal women kept watch by turns. Her strict orders were that whoever entered the palace after the first watch of the night should be arrested. Intimacy between servants and maids was strictly forbidden. Bahu Begum always went out in a spectacular procession, either seated in a Sedan chair or in a similar conveyance. Such processions were always headed by drum beaters. During the lifetime of her husband and her son, no one else was permitted to go out in such a procession except her. Even the Nawab Asaf-ud-daulah respected her high status to such an extent that he forbade the steward of the Begum [from] dismounting from his animal as a mark of respect to himself. He told the steward that “You are riding with a superior, continue to ride.” On the contrary, Asaf-ud-daulah himself dismounted from his elephant and holding the foot of the palanquin of the Begum walked politely a few steps, as a gestures of respect to the great lady. During her stay at Lucknow, every day at all meal times forty dishes were sent to her by Asaf-ud-daulah to her residence. She used to take only one meal a day and naturally all the delicacies were enjoyed by her maid and followers. Maulvi Fazli Azim Khan, in charge of [the] house-hold kitchen suggested to Asaf-ud-daulah that instead of sending food which the Begum did not eat, a cash payment of Rs. 400/- be given to her, so that she might utilize the amount as she pleased. The proposal was placed before her and it was accepted.

The great Begum who had been brought up by Emperor Muhammad Shah and who was married into the family of Wazirs, passed most of her life in such splendour that staggers modern imagination. Faiz Buksh wrote that in the entire family of Asaf Jah, Nizam-ul-mulk “there was not a woman left of so great distinction and rank, bearing and dignity, and no women in all thirty-two subahs of India can be held up in these days as her rival in either the grandeur of her surroundings or the respect, she could command.” “The chiefs of the Bangash provinces were of no greater consideration compared to her than were her police officers.” In the light of the exalted position enjoyed by her, it seems all the more tragic that she was exposed to the humiliation at the hands of the English by her own son and his self-serving officials.

The great Begum who had been brought up by Emperor Muhammad Shah and who was married into the family of Wazirs, passed most of her life in such splendour that staggers modern imagination. Faiz Buksh wrote that in the entire family of Asaf Jah, Nizam-ul-mulk “there was not a woman left of so great distinction and rank, bearing and dignity, and no women in all thirty-two subahs of India can be held up in these days as her rival in either the grandeur of her surroundings or the respect, she could command.”

Palace of Nawab Shuja-ud-Daula, Lucknow. Thomas and William Daniels, Late 18th Century.

Bahu Begum was very rich and her establishment resembled a small kingdom. As the foster child of the Delhi Emperor, Muhammad Shah, and respected wife of Wazir-cum-Nawab of a rich province, she was showered with many jagirs, houses, gardens, certain rights of collecting taxes and levies, besides being in possession of fabulous jewellery, costly apparel and silver and gold vessels and other articles. After the battle of Buxar, Shuja-ud-daulah made it a principle to give her half of whatever came out of his revenue or income. She practically governed Faizabad after her son left for Lucknow.

Faiz Buksh listed such places and rights as bestowed upon her in the form of jagirs. These were, firstly the larger Mahals, such as Solan, Simrauta, Mohan Gunj, Jias, Kora, Prasidhipur, Rukka, Altha and Gonda and the zilas like Mirganj, Sindh, Ghoriabad, Nawab Ganj, Garhaiya, Fursat Ganj and Banaura which were all located in the south of Faizabad. Some more were located at other places such as Nawab Ganj in the north. Tanda in the east and Ismail Gunj near Lucknow to the west of Faizabad. Few more zilas were Ismailgunj (situated near Yahyagunj), Wazirganj (situated between Mohan and Lucknow), Unnao Khas and Begum Bari. He also mentioned certain rights of the Begum to levy taxes, such as Galladagh and Fatehdagh (rights of cattle branding) in the entire province. Thus the Begum was in possession of Jagirs, Ganjes, gardens and rights on meat markets and Mints of the entire province. The jagirs were completely rent free lands.

Nawab of Awadh Saadat Ali Khan I.

Allegations were levelled at Bahu Begum to say that her faithful officials and subordinates sometimes, with or without her knowledge and without the Nawab’s sanction, simply appropriated certain places and markets. Asaf-ud-daulah once complained to Warren Hastings that some of the places claimed by the Begum were not in her possession during the life time of Shuja-ud-daulah and that she had unjustly appropriated them. Similarly Saadat Ali Khan repeated the same complaint in his memorandum to the Governor-General. He wrote, “I request His Lordship will have the goodness to send for Darab Ali Khan and desire that exclusively of the jagir, such property, land, Bazars, gardens etc. to a considerably extent belonging to the Sircar as the offers of Her Highness unjustly and without requisite vouchers (sanads) appropriated since four years.” Bahu Begum was the virtual ruler over these places. Saadat Ali Khan regarded the power wielded by the Begum as detrimental to his own prestige. It was like an “imperium in imperio” and he requested the Governor-General for certain curtailment of her powers and interference in the matters of justice, tax collection etc. in her own jurisdiction.

The Begum exhibited remarkable capacity in the maintenance of order and discipline and proved her talents in her administrative ability. It was no ordinary task to maintain and supervise such a huge establishment.

The Begum exhibited remarkable capacity in the maintenance of order and discipline and proved her talents in her administrative ability. It was no ordinary task to maintain and supervise such a huge establishment.

The sources of information regarding the division and administration of the jagirs are of course limited to the narration of Faiz Buksh and the stray official accounts of the Company. In spite of the paucity of material, the capacities of Bahu Begum are clearly revealed and are discernible in these accounts. She had the insight to detect the calibre and abilities of people and her choice of men women to various posts, big and small, was invariably commendable. She did not pay any attention either to the consideration of relationship or any other recommendations. To cite an example, her relation Mirza Muhammad Taqi very much wanted the administration of Mahal Gonda to be conferred on him. He tried to influence her through her trusted steward Jawahar Ali Khan. The Begum refused to appoint him saying that he was a spend-thrift and would lose the whole income within a short period.

Although the Begum’s jagirs were scattered, she efficiently managed them through a hierarchy of officials, who were efficient, loyal and sincere to her. For large Mahals which were eight according to Faiz Buksh, Collectors (for revenue collections) and Faujdars (for magisterial purposes) were appointed. For others either Police Officers or sub-faujdars or collectors and Tehsildars were appointed according to necessity.

Curiously enough the duties of supervision of these officers were entrusted to the eunuchs who were in charge of her household. Their loyalty and trustworthiness was the reason for this policy. Hence Jawahar Ali Khan was appointed Bahu Begum’s steward (Nazir) and was in charge of eight Mahals in the south which were all included in Salon. He was also responsible for the collection of tolls of Wazir Ganj, Unnao Khas and of Ismail Ganj (of Gorakhpur division). He was Superintendent of the Begum’s carriages which were about 900 in number. Another eunuch Bahar Ali Khan was in charge of Tanda and Nawabganj and he was the Treasurer and Superintendent of the Begum’s kitchen. Basant Ali Khan, another eunuch was in charge of Begum Bari. The arrangements worked out smoothly as these officers sent their agents to look after the duties that were assigned to them. These agents were paid from their own pockets. These arrangements were made only after the approval of Bahu Begum.

The officers, the Collectors and the Faujdars had a force of armed men in order to maintain their position and discipline, resembling the Feudal system of the Mughal period. To illustrate, Jawahar Ali Khan has a regiment in black uniform and a cavalry. He maintained an irregular force of 18 companies. Bahar Ali Khan had 300 sepoys in addition to armed servants employed for revenue collection from his mahals. Shikoh Ali Khan who held Ismail Ganj near Lucknow had a company of regulars. Basant Ali Khan has a strength of 10 to 20 sepoys. Akhwand Ahmad Ali Khan has a force of 50 Sabit Khanis. Bikhari Khan at Simrouta had fifty men at his disposal; Ghasi Khan at Naurahi has a company of irregulars. The total strength of all such forces, regular and irregular was about 10,000 men.

Memoirs of Faizabad and Delhi by William Hoey was the English translation of Tarikh-i-Farahbukhsh, written by Faiz Baksh in Persian.

Although the Begum’s jagirs were scattered, she efficiently managed them through a hierarchy of officials, who were efficient, loyal and sincere to her. For large Mahals which were eight according to Faiz Buksh, Collectors (for revenue collections) and Faujdars (for magisterial purposes) were appointed. For others either Police Officers or sub-faujdars or collectors and Tehsildars were appointed according to necessity. Curiously enough the duties of supervision of these officers were entrusted to the eunuchs who were in charge of her household.

Bahu Begum had a personal army to guard her palace and to accompany her wherever necessary. Two thousand mounted soldiers under the command of Ahmad Ali were appointed for her. She had also appointed one Memraj Khan Mewati for Salon as Faujdar. He had 25 mounted men and 700 on foot. Bahu Begum had ordered 150 of them to remain in Faizabad to guard her palace. She had about 25 boats of the purposes of communication across the rivers.

The management of the establishment was distributed amongst her officers thus :–

After the departure of Asaf-ud-daulah, the city of Faizabad came under Bahu Begum and she probably entrusted Jawahar Ali Khan at the time to maintain law and order.

Jawahar Ali Khan, with the sanction of the Begum, made the appointments of Collectors, Faujdars and such others. He was the Nazir (steward) and the representative of the Begum. He issued al the letters of appointment, orders for lease of land, dismissals etc. under her seal. He also had other miscellaneous duties and there 8 to 10 thousand men of all cadres under him in various capacities. Bahar Ali Khan was the Treasurer and acted as her envoy. Some of the men appointed to different posts were as follows :–

Aga Muhammad Kashmiri … A Sub-Collector of Mahal Para Sodhi.

Bhikari Khan … Faujdar of Mahal Simrouta.

Ghasi Khan … Faujdar of Mahal Naurahi.

Shamsher Khan … Tahsildar of Tanda.

Muhammad Bahram … Faujdar of Salon Khas.

Kasim Ali … Sub-Collector of Salon Khas.

Bhawani Singh … Police Officer in Mirganj

Akhwand Ahmad Ali Khan … He was the local agent of Jawahar Ali Khan and also for the lease of jagirs.

Nishat Ali Khan … He was in charge of the collection of the income.

Baqr Ali Khan … Collector of Tanda.

Chait Rai … Accountant.

Khairu-un-nisa … Letter Writer.

Sidi Sikandar … Astrologer.

Masiah … Physician.

The Begum’s exact total income from the jagirs was not referred to in any of the accounts. The returns deposited by her chief eunuchs, i.e. Jawahar Ali Khan and Bahar Ali Khan were five lakhs and twenty-five thousand rupees. The Resident John Bristow in his letter to the Governor-General stated that her income was about 7 lakhs of rupees and that her personal expenditure was about Rs. 12,000/-. Abu Talib wrote that once he was in charge of the two jagirs belonging to Bahu Begum and her brother Salar Jung. He stated that he collected the combined rental value of the two jagirs as 20 lakhs of rupees while declaring that Salar Jung’s jagir yielded only 7 lakhs of rupees. If so, Bahu Begum’s jagir would fetch an amount of 13 lakhs of rupees. On the other hand, the Begum once told her brother that her jagir yielded only 4 lakhs of rupees. The revenue which she drew from her jagir might be the figure deposited by her eunuchs. This it would be approximately about six lakhs of rupees and allowing for an expenditure of one and a half lakhs, she might be depositing at least 4 lakhs of rupees in her safe.

Bahu Begum was generous and kind, besides being efficient; a fact which was testified by Faiz Buksh, who served under Jawahar Ali Khan in these words, “Her employees, servants, great and small enjoyed peace and security. They had neither the hardship of a campaign nor the griefs of war and battle to undergo. They drew their salaries month by month, paid to them even in advance, in full and without deduction or drawbacks; and every man lived happily and contented night and day.”

Bahu Begum was generous and kind, besides being efficient; a fact which was testified by Faiz Buksh, who served under Jawahar Ali Khan in these words, “Her employees, servants, great and small enjoyed peace and security. They had neither the hardship of a campaign nor the griefs of war and battle to undergo. They drew their salaries month by month, paid to them even in advance, in full and without deduction or drawbacks; and every man lived happily and contented night and day.”

Bahu Begum never levied a high rent on the lands let by her. A reasonable fixed amount was announced, so that the tenant might not be deprived of the profit with which they could maintain themselves comfortably. Naturally such generosity led many ambitious and selfish persons to covet her lands. Bhawani Singh who held the village of Salon and two other villages paid a fixed rent of only Rs. 8,000/- per annum, the actual value of which was Rs. 18,000/- per annum. He did not pay regularly even such a small amount. Still the Begum did not dismiss him. Another aspirant Maulvi Fazal Ali taking advantage of the situation coveted these lands and approached Nawab Asaf-ud-daulah for help. The Nawab asked Jawahar Ali Khan, the steward of the Begum to settle the matter without the knowledge of the Begum. Jawahar Ali Khan, however, reported the matter to the Begum who stubbornly refused to change the person. Matters reached a climax and the Nawab desired to install Fazal Ali by force. Unruffled by such a threat, Bahu Begum alerted her men to be ready, if necessary, to fight. Haidar Beg Khan, the then Minister, cleverly intervened and waited for another opportunity for retaliation against the Begum. Faiz Buksh regarded the above incident as a preface to spoliation of the Begum’s property.

Asaf-ud-Daula

The Begum’s domestic establishment was huge and consisted of many persons who subsisted on her munificence. Some of them were the eunuchs, Mian Idrak, Firasat, Aqalmand, Yaqut Khan, Aqalmand Kaptan, Mian Khurram, Nikhat Suhaib, Darab Ali Kham, Mian Taib, Nazabat, Khushdil, Yaqut, Khursheed, Sakhawat, Basharak, Rozafzun, Zamurrud, Mujatha, Zamarrud Darbari, Khush Chashm, Zulfiqar Mian Daualat, Ishrat and others. They were maintained to do various jobs within and outside the palace. There were servants attached to the elephant stalls, the stables and coach houses, household servants, messengers, slaves, mace bearers, accountants, and artisans attached to the factories. In all, she had a total of about a hundred thousand “who earned their bread directly and indirectly through her bounty and felt happy and secure as though they were in a mother’s lap.”

Bahu Begum was the first amongst the chief consorts who began to interfere directly in matters relating to the state and to confront the vicious counter activities of the ministers which led to disintegration of the state and her own ultimate downfall. It started with the appointment of the Minister Murtaza Khan Mukhtar-ud-daulah. She did not appreciate it and merely regarded it as a foolish act of her weak son Asaf-ud-daulah since Murtaza Khan was an enemy to her family. She became convinced of the evil influence of this person on her son by various incidents such as – (1) Asaf-ud-daulah’s untimely demand for money while she was in mourning; (2) his transfer of capital from Faizabad to Lucknow and (3) the treaty of Faizabad of 1775 leading to the cession of Benares to the Company. She became alarmed at the continuing influence of such a person upon her son. She, therefore, availed of an early opportunity to express her dissatisfaction of Murtaza Khan and requested the Governor-General to dismiss him. She suggested the names of Muhammad Eilish Khan and Muhammad Bashir Khan for the administration of the state and assured Governor-General of good administration by them. She wrote “by them the revenue will be collected and whatever sums are due to the English Chiefs, I will cause to be paid out of the revenues.” Thus she offered to take the responsibility on herself. This was the first occasion when a Begum invited the interference of the English in the state and domestic matters of Awadh.

Bahu Begum was the first amongst the chief consorts who began to interfere directly in matters relating to the state and to confront the vicious counter activities of the ministers which led to disintegration of the state and her own ultimate downfall. It started with the appointment of the Minister Murtaza Khan Mukhtar-ud-daulah.

The result of this unprecedented and bold suggestion, aggravated the enmity of Murtaza Khan towards the Begum. The Board of Governor-General-in-Council, however, did not welcome her interference and turned down her proposal by replying to her that “the Nawab was the master in his own Government and that we cannot with propriety interferer.” Providentially for the Begum, Murtaza Khan soon met with a violent death at the hands of his avowed enemies.

Murtaza Khan had deliberately avoided the payment of the salaries to the troops stationed at Faizabad, where the Begum had stayed back after Asaf-ud-daulah transferred his capital to Lucknow. This was probably to create disturbances at that place in order to manoeuvre circumstances to land the Begum into difficulties. For, no sooner that he died that the Begum had to confront with the revolt of the Red Coat Cavalry Regiments. These were the three Regiments which consisted of three thousand men and were headed by Bagh Rai, a Hindu. They had not received their pay from the treasury for the past one year and were in great distress. Their repeated appeals to the minister and the Nawab were of no avail. In the end, they besieged the palace of Bahu Begum and her steward in 1776 A.D. (7th Shawwal 1190 H), and demanded from her their pay on the ground that they had been guarding her palace. At this moment, another Artillery force consisting of five hundred Mughal men with fifty or sixty of their guns also joined the rebels and made the situation critical and dangerous. The rebels indulged in violent and unruly acts, such as snatching away the food that was brought to the Begum, abusing the servants and even hurling insults upon her. When “a whole day, night and one watch of the second day” had passed, the helpless Begum then ordered her steward, Jawahar Ali Khan to pay their salaries on condition of surrender to her of their muskets, flint locks and guns etc. After this payment Faizabad became bereft of any security as all the soldiers left the place. The shrewd Begum immediately took charge of the city and posted her own troops at all key positions to preserve peace and order.

In this connection it may be submitted that the Begum had foreseen such disturbances and the incipient rebellion of the soldiers. She had written to the Resident at Lucknow and had warned him. But the Resident had turned a deaf ear to her appraisal of the situation. She again despatched another letter after the event took place and expressed her fear of such recurrences in the future and sought his co-operation by requesting his to fortify Faizabad and her palace.

While these events took place the attitude of Asaf-ud-daulah remained unexpectedly very aggressive. Misinformed by his men and suspecting the Begum’s conduct, he hurried to the Resident and bitterly complained to hum that Bahu Begum had “thought proper to put her own people into all the offices in the town (Faizabad) and displaces his (men).” He accused her of taking into custody some sepoys and a Soubahdar (Subahdar) who were guarding the stores of the Government, seizing the gates and announcing to the public that she had bought the town for the money she paid for the troops. His accusation undoubtedly had some truth. As one of the Begum’s men, called Yar Ali, without the knowledge of the Begum had attacked Ghulam Hussain and his men who were in-charge of the arsenal at Faizabad and who had nothing to do with the revolt. The helpless Ghulam Hussain had to report to Asaf-ud-daulah about it.

Murtaza Khan had deliberately avoided the payment of the salaries to the troops stationed at Faizabad, where the Begum had stayed back after Asaf-ud-daulah transferred his capital to Lucknow. This was probably to create disturbances at that place in order to manoeuvre circumstances to land the Begum into difficulties. For, no sooner that he died that the Begum had to confront with the revolt of the Red Coat Cavalry Regiments…they besieged the palace of Bahu Begum and her steward in 1776 A.D. (7th Shawwal 1190 H), and demanded from her their pay on the ground that they had been guarding her palace.

Asaf-ud-daulah then ordered his armies to proceed to Faizabad to control the situation. In this connection Faiz Buksh wrote that an arrogant officer, Imam Buksh was selected by Asaf-ud-daulah for this purpose. Seven hundred Turkish irregulars were attached to him and he was instructed to get the heads of the two trusted eunuchs of Bahu Begum. But the minister, Hasan Raza Khan perceived much combustible material in such hasty orders. Fearing a possible bloodshed if Imam Buksh were to go, he quietly approached the Resident and requested him to persuade the Nawab and to send him also to Faizabad.

The Resident, John Bristow, immediately agreed to such a proposal as he took stock of the situation and realised the mischief of some of the supporters of Asaf-ud-daulah who exaggerated the Begum’s conduct and made capital out of it “in order to cause ill-will between her and His Excellency.” The Resident them wrote to the Begum assuring her of safety and protection from any such recurrences. He agreed to pay her Rs.70,000/- as a compensation for the amount which she had paid the troops. In the end she did not even received any such compensation as Hasan Raza Khan took away the muskets after assuring her to send the promised sum within a week of his arrival at Lucknow, which was never complied with.

The entire episode thus testifies to the mischief and disloyalty of the ministers and some of the supporters of the weak Asaf-ud-daulah, who availed of every possible opportunity to intensify tensions between Bahu Begum and her son. This episode, while indicating the Begum’s alertness and capacity for successfully handling a crisis, by timely and precise action, also testifies to her lack of complete control over her officers mostly due to the strict observance of the purdah. She was obliged to depend upon her servants, as for example Yar Ali, who indulged in careless and unbridled activities which naturally involved her in complications.

Shujah-ud-Daulah & his sons.

The renewal of the tussle between Bahu Begum and the minister, the task of the final appropriation of her property and jagirs and her subjection to abject humiliation began with the rise of Haidar Beg Khan. He was also an enemy to the House of Shuja-ud-daulah and was a notorious person for “extortion, oppression, selfishness and perfidy.” (History of Asaf-ud-daulah, p.9. The writer wrote that “Hydar Beg Khan and his brother Nur Beg Khan committed embezzlement of revenues under Beni Bahadur, the naib of Shuja-ud-daulah. In the course of their punishments, Nur Beg Khan was killed and Haidar Beg Khan was saved by the timely intervention of the benevolent Bahu Begum…Haidar Beg Khan could not forget the death of his brother and blamed Shuja-ud-daulah for such a tragedy.”) He was described as “vindictive by nature and reached harm to all his benefactors.”

The immediate reason for the conflict between Bahu Begum and Haidar Beg Khan was due to the eunuch, Almas Ali Khan. Though a good and capable servant of the state, Almas Ali Khan had the habit of appropriating a part of the revenue on some pretext or the other. Haidar Beg Khan demanded rupees seven lakhs from him as settlement for the misappropriated amounts. Almas Ali Khan was piqued and decided to bring about his downfall. The task was easy for Almas Ali Khan as Haidar Beg Khan himself was corrupt and had betrayed the trust of Bahu Begum. Almas Ali Khan, therefore, persuaded Nawab Asaf-ud-daulah, Bahu Begum and her brother Salar Jung to remove Haidar Beg Khan. As the matter was to be referred to the Governor-General for approval, the task of accomplishing it secretly was entrusted to Bahu Begum. The Begum was readily persuaded to undertake it because she was convinced of the competence of Almas Ali Khan as a good administrator. She had also in the mind the renewal of certain guarantees and concessions which were due to her. She despatched her trusted confidant Bahar Ali Khan to Calcutta with this mission. Haidar Beg Khan soon came to know about the secret mission through one of the servants of the Begum, called Yaqut. He was naturally aghast at such a secret plan aiming at his destruction and the active involvement of Bahu Begum in it. For some time past he had not indulged in any disrespectful act against the Begum. So, while he was trying to find out the identity of the person who had instigated the Begum against him, Hasan Raza Khan urged him to first strike at the mission. Perhaps Hasan Raza Khan regarded the danger to Haidar Beg Khan as an evil omen to his own downfall.

The entire episode thus testifies to the mischief and disloyalty of the ministers and some of the supporters of the weak Asaf-ud-daulah, who availed of every possible opportunity to intensify tensions between Bahu Begum and her son. This episode, while indicating the Begum’s alertness and capacity for successfully handling a crisis, by timely and precise action, also testifies to her lack of complete control over her officers mostly due to the strict observance of the purdah.

Haidar Beg Khan immediately wrote to the Governor-General, enclosing a draft of twelve lakhs of rupees with a request not to entertain the proposals of Bahar Ali Khan. He proposed to the Governor-General that “a sum of ten millions of rupees would be sent to him ‘as a mark of gratitude and tribute to His Excellency’, if his request is complied with in turning out Bahar Ali Khan’s proposal.” Such a request had no doubt some weight as he wrote in the capacity of the deputy minister of state.

Warren Hastings who had at first received Bahar Ali Khan in a warm and cordial manner turned indifferent to him due to Haidar Beg’s profitable proposal. Faiz Buksh wrote that Bahar Ali delayed foolishly in negotiating the amount which Warren Hastings wanted from him. Yaqut has maliciously worked upon Bahar Ali so that the negotiations be protracted and there could be enough time for Haidar Beg Khan to correspond with Warren Hastings. In this episode Haidar Beg scored over the Begum. Her bid to demean his position was abortive. The entire transaction also opened up a very powerful channel of negotiations in the shape of large sums of money which determined the future policy of the Governor-General towards Awadh and its Begums. It also worked towards the confiscation of the Begum’s property as would be seen below.

Haidar Beg Khan then patiently worked for an opportunity to belittle Bahu Begum. He avoided a premature occasion, in the case of Bhavani Singh, when Asaf-ud-daulah and Bahu Begum had become seriously involved in an open conflict. Haidar Beg Khan did not consider the time right for executing his evil designs. He, therefore, posed as a sincere servant of his master and pacified Asaf-ud-daulah against his mother.

The modus operandi started with the announcement of Warren Hastings’ visit to Awadh; the subsequent rebellion of Chait Singh and the treaty of Chunar (19 Sept. 1781). Large arrears had accumulated due to non-payment and squandering of revenue money by the Nawab and his minister. It was at this stage that Haidar Beg Khan chose to reveal to Asaf-ud-daulah the gravity of the result of the payment of the vast arrears to the Company which in any case could never be met with from the meagre revenues of the State. He impressed upon him that the hopelessness of the situation could only be retrieved by the confiscation of Jagirs of the State. Asaf-ud-daulah could never imagine what actually Haidar Beg Khan aimed at. He, therefore, simply believed in this argument and decided to approach Warren Hastings with this proposal. It may be noted here that the main cause which is cited and analysed in a critical way by the apologists of Warren Hastings for giving permission to Asaf-ud-daulah for confiscating the Jagirs of all including the Begum’s was a manoeuvred act of Haidar Beg Khan.

Large arrears had accumulated due to non-payment and squandering of revenue money by the Nawab and his minister. It was at this stage that Haidar Beg Khan chose to reveal to Asaf-ud-daulah the gravity of the result of the payment of the vast arrears to the Company which in any case could never be met with from the meagre revenues of the State. He impressed upon him that the hopelessness of the situation could only be retrieved by the confiscation of Jagirs of the State.

The immediate cause of the confiscation of the Begum’s property derived from the situation arising out of the emeute at Banaras and the supposed ill-treatment of Col. Hanny’s men by the Begum’s eunuchs. This incident was fully exploited by Haidar Beg Khan to his own advantage. It may be said that Bahu Begum’s involvement in the uprising of Chait Singh and the consequent events was of omission only. She was not actively involved as alleged by Haidar Beg Khan and Warren Hastings. In fact it was Haidar Beg Khan who first treacherously opened up communications with Chait Singh, while he was enroute to join Hastings, as he “considered it politic and prudent to do so; in order that he might eventually join the side which he found prevailing.” If Haidar Beg Khan could be clever enough to play such a double game, it was but natural for an anxious mother like Bahu Begum to advise Asaf-ud-daulah not to join Warren Hastings against such wide-spread and formidable rebellion. While the real culprit Haidar Beg Khan escaped retribution, Bahu Begum by her cautionary advice which in any case was disregarded, provided another evidence to Warren Hastings indicative of her disloyalty.

When Haidar Beg Khan reached Banaras, he tried to convince Warren Hastings about the involvement of Bahu Begum and Sadr-i-Jahan Begum in Chait Singh’s rebellion. He told Warren Hastings that “all was done at the instigation of the Begum’s eunuchs. I should not wonder even if the Begum had given a hint to him.” As fate would have it, while Warren Hastings was pondering over the truth of this statement, John Gordon’s letter, complaining about the conduct the men of Bahu Begum reached his hands and tilted the scale completely against the Begum. His firm belief in the hostility of Bahu Begum led to the treaty of Chunar and its vigorous implementation.

In the light of the above evidence, Mill was right in believing that, “the only evidence against the Begums in Chait Singh’s rebellion, is based on rumour and hearsay, and that this evidence is in the form of affidavits taken after Hastings decided to punish the Begums by withdrawing the Company’s support.” An extract from the letter sent by the Court of Directors to the Governor-General would show that they too doubted the Begum’s involvement.

Tarikh Badshah Begum by Muhammad Taqi Ahmad, a translation of the Persian Waqaa-i-dil pazir by Abdul Ahad.

It is significant to note that Haidar Beg Khan’s slow and systematic plan to destroy Bahu Begum, not only caused the Residents to succumb to this stratagem but ensnared a man like Warren Hastings also. Hastings sent a directive to Middleton in 1782 A.D. in connection with the resumption of the Begum’s Jagir. “You must not allow any negotiations or forbearance, but must prosecute both services till the Begums are at the entire mercy of the Nawab, their jagirs in the quiet possession of his amils and their wealth in such charge as may secure it against embezzlement.” Such a statement appears in great contrast to his previous sympathetic comments on the Begum in 1776 A.D. He then wrote “All my present wish is that the orders of the Board may be such as may obviate or remove the discredit to the which the English name may suffer by the exercise or even the public appearance of oppression on a person of the Begum’s rank, character and sex.”

Warren Hastings not only assented to the Nawab’s proposal for resuming the jagirs but also used “a degree of compulsion to induce him to carry out” the process of confiscation. The Nawab in spite of all his weaknesses was reluctant to perform the actual act of confiscation. He knew pretty well that the jagirs were duly given to the Begum and that he had no right to confiscate them. Warren Hastings believed in the doctrine “that the end justifies the means” and, therefore, cared more for the interests of the Company and its sound financial condition than to meet justice to the Begums.

It is significant to note that Haidar Beg Khan’s slow and systematic plan to destroy Bahu Begum, not only caused the Residents to succumb to this stratagem but ensnared a man like Warren Hastings also…Warren Hastings not only assented to the Nawab’s proposal for resuming the jagirs but also used “a degree of compulsion to induce him to carry out” the process of confiscation. The Nawab in spite of all his weaknesses was reluctant to perform the actual act of confiscation. He knew pretty well that the jagirs were duly given to the Begum and that he had no right to confiscate them.

Nawab Asaf-ud-daulah, however, being as incompetent as he was, did not pay the dues to the Company even after his appropriation of the jagirs. Haidar Beg Khan once again played the party of a villain when he suggested to the Nawab to charge his mother yet again for the money due to the Company. Goaded by his minister and pressed by the Resident, Asaf-ud-daulah at last agreed to despatch troops to coerce the Begums.

Strangely enough, most of the contemporary Indian writers did not write about the confiscation or the resistance offered by Bahu Begum; whereas the English records stated that she took immediate steps to defend her jagirs. They alleged that she went as far as to write a threatening letter to the Resident who was obliged to call upon Colonel Morgan for a Regiment to support the amil (Mirza Shafi Khan Mughal Irani) in the execution of the Nawab’s commands (Foreign Dept. Sec. 14th January 1782, No. 6. Bahu Begum wrote “should the country be lost to me it shall be lost to all. I give this intimation. Note it.”).

Eventually, the fort of Faizabad was captured, and the trusted eunuchs of Bahu Begum were arrested and placed in iron chains. Faiz Buksh gave a very graphic picture of this poignant event. Abu Talib wrote briefly that “The foolish Khwajasaras were determined to stand a siege with the three or four thousand men they had, but the Nawab Begum, after the guns had been mounted and appliances of war was inspected, sent the two Khwajasaras to her son and tool refuge herself in the palace of Nawab Aliya (Sadr-i-Jahan Begum) and this unfortunate lady’s jagir was also confiscated, because she could not help giving protection to her son’s widow. The Wazir (Asaf-ud-daulah) who owed the two Khwajasaras a grudge from his boyhood not put them in iron fetters and omitted no detail of bodily inflictions, outrages and indignities. He sacked his mother’s residence and took from it 50 lakhs of rupees in cash and 50 lakhs of property, in gold, silver, and clothes, and returned to Lucknow. Haidar Beg Khan, who owed his very life to the Begums and Bahar Ali Khan, did not utter even a word in their favour but seems to have been the cause for the aggravation of their misfortunes.”

Asaf-ud-Daulah watching a cockfight with a British officer. This picture most likely depicts a famous incident between Colonel Mordaunt & the Nawab which took place in Lucknow, c. 1774.

Ironically, the strength of the support Haidar Beg Khan had rendered to the Resident, led Middleton to request Hastings to favour him with some special mark of his appreciation.

It becomes obvious that in a situation where the Begum had to reckon with the unbridled greed of the English on the one hand, and the unscrupulous machinations of her ministers on the other, while the Nawab played into the hands of either, she could not hope for a modicum of success. The motif repeats itself in the deposition of Wazir Ali.

It becomes obvious that in a situation where the Begum had to reckon with the unbridled greed of the English on the one hand, and the unscrupulous machinations of her ministers on the other, while the Nawab played into the hands of either, she could not hope for a modicum of success. The motif repeats itself in the deposition of Wazir Ali.

To begin with, Bahu Begum approved the succession of Wazir Ali, though she knew that he was not the heir and son of Asaf-ud-daulah. She continued to support him although Wazir Ali displeased her by his indecent haste in occupying the masnad, while the body of Asaf-ud-daulah was still lying in the palace. Later, Wazir Ali became unpopular amongst his kith and kin and friends due to his harsh tongue and cruel acts. He was very hostile to the Company too.

The question of deposing him was mooted. At this juncture the Begum tried to save the situation by attempting to install one of Shuja-ud-daulah’s sons by another marriage. She was aware that the British favoured Mirza Mangli (he was the second son of Shuja-ud-daulah but not by Bahu Begum) who was “warmly attached to the English, fond of their company and desirous of learning their language…” She wrote a letter in favour of Wazir Ali to the Governor-General Sir John Shore who nursed the idea of placing Mirza Jungli upon the masnad. She preferred him to Mirza Mangli due to his aloofness from the influence of the English. She thought of installing a strong ruler who could keep the English at bay.

Shore charged her with the intention of becoming the de facto ruler. He wrote to Dundas (President, Board of Control) that she was determined to support Wazir Ali and that she “was disposed to maintain her own control, and in this view has not only leagued with Almas Kham, but the young Nabob whose conduct though grossly indecent and degrading, she defends.” He was, therefore, determined to personally visit Awadh, and if necessary, by force to remove Wazir Ali and replace him by his own candidate who would be amenable to their demands.

Bahu Begum could not comprehend the deep and ulterior motives of the English. She thought she could persuade Shore, especially because many of the nobles supported her choice. She, therefore, took the unprecedented step of personally meeting and negotiating with the Governor-General at Bibiapur. Her initiative was of no avail because of the presence of Wazir Ali at the meeting. She was, understandably inhibited on grounds of delicacy and etiquette. The shrewd Governor-General on his part did not want to displease the Begum until he was sure of Mirza Mangli, and his safe arrival at Lucknow. He also wanted the Begum’s countenance to justify the act of deposing Wazir Ali on the ground of illegitimacy. He, therefore, did not make public his intention to install Mirza Mangli. Instead he called a conference of an elite of the court and spoke to them in a diplomatic way about the birth of Wazir Ali, which necessitated his expulsion from the masnad. He then wondered as to who could be the successor. Thereafter in a tactful manner he mentioned the desirability of Mirza Mangli’s nomination. During the entire talk he cleverly mentioned, more than once that he considered himself and the Company to be the guarantee of the rights and dignity of the Begum. Such an open proclamation of respect for the Begum on the part of English dumbfounded the members present. They, however, were not in a position to disagree with Shore’s statements and reasserted their as well as Bahu Begum’s confidence in the Governor-General. Further, Shore having achieved his point was ready to concede the demand of the supporters of the Begum who proposed that Mirza Mangli should receive his robe of investiture from her.

She was aware that the British favoured Mirza Mangli who was “warmly attached to the English, fond of their company and desirous of learning their language…” She wrote a letter in favour of Wazir Ali to the Governor-General Sir John Shore who nursed the idea of placing Mirza Jungli upon the masnad. She preferred him to Mirza Mangli due to his aloofness from the influence of the English. She thought of installing a strong ruler who could keep the English at bay.

Satisfied by his dealings and arrangements, Shore then directed Bahu Begum to go back to Lucknow, while once again expressing loudly his confidence in her and reliance upon her assistance and co-operation. Any possible doubts in the mind of the Begum was allayed by Shore’s tactful handling of the situation. Once more, her better judgement regarding the state of Awadh came to naught.

In spite of the Begum’s compliance, she was said to have made an effort according to Shore, at the last moment to prevent the succession of Mirza Mangli by sending messengers either to Tafazz-ul-Hussain Khan to win him to her side or to the Governor-General informing him of a threat of rebellion by an officer-in-charge of the Artillery.

The Indian Chroniclers did not corroborate such an account but wrote differently. According to them she discouraged any of Mirza Jungli’s attempts of resistance. Shore’s conviction was probably based on some of the timid gestures of resistance shown independently by the sympathisers of Mirza Jungli in the name of Bahu Begum. Bahu Begum quietly got reconciled to Mirza Mangli’s nomination and was the first to put her seal to the deed of accession of Mirza Mangli.

Bahu Begum’s fears turned out to be true with regard to Mirza Mangli who came to be known as Saadat Ali Khan, the friend of the English; in his eagerness to ascend the masnad he readily agreed to the conditions which were ruinous to the state.

Shore kept his word of protecting Bahu Begum and her interests. He directed Saadat Ali Khan to comply with all her requests and a deed was accordingly made.