ARCHIVE

An Indian in New York (1913-1916)

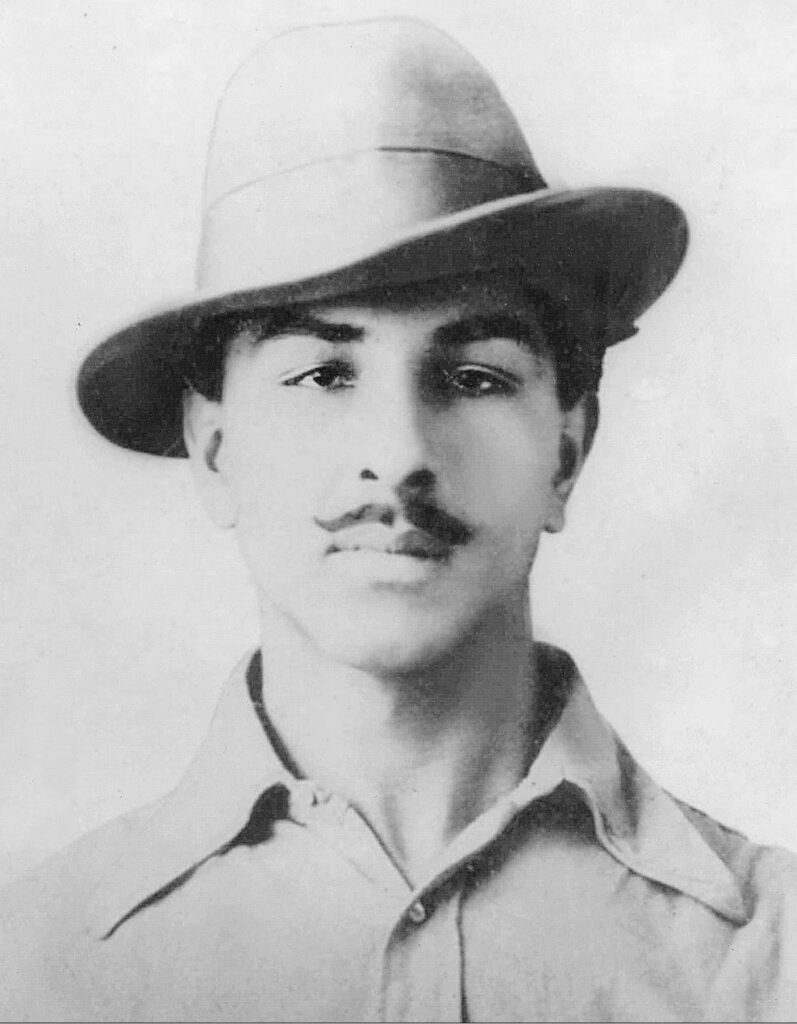

A young Ambedkar during his Columbia University days. Wikimedia Commons.

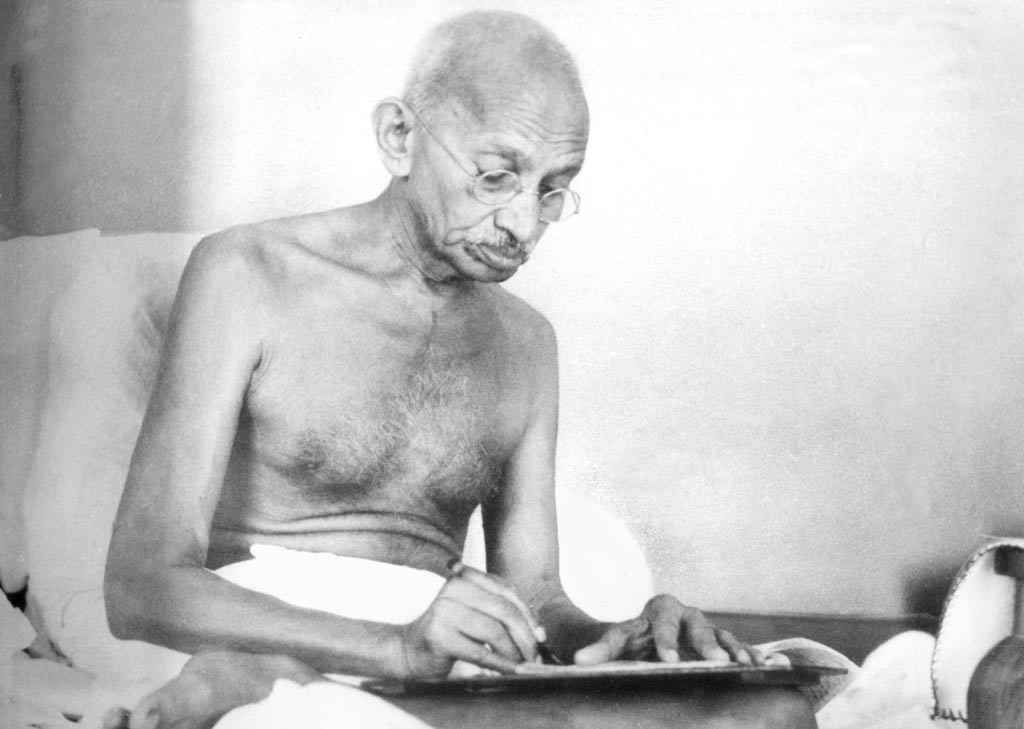

Young Ambedkar’s emerging academic understanding of caste was helping him give systematic expression to his many prior years of the lived experience of systemic caste prejudice. Alongside and as impetus to this were also his widening experiences regarding issues of race, class and gender. To some extent, this new exposure was a result of his coursework at Columbia. But much of this exposure came more concretely, from treading the streets of upper Manhattan and Harlem.

Describing his usual New York day, Ambedkar emphasized that the vast majority of his time, some 18 hours daily, was spent on campus, either attending lectures and seminars, or otherwise working in Columbia University’s magnificent and exceptionally-stocked Low Library. But he often ate off of campus, opting to eat only one meal per day to save both time and money. For food he spent on average $1.10 daily, which would buy him a cup of coffee, two muffins, and either a meat or a fish dish. He was on a tight budget. New York City living was not cheap, and he had to send money home to his family as well. But that was not all. His voracious reading habit, that had been cultivated in young Ambedkar within the shadow thrown by the Bombay-gothic tower of Elphinstone, had only grown stronger atop the grand staircase of the Roman-neoclassical library of Columbia. Ambedkar was now in the first stage of what would turn out to be a life-long obsession with collecting books. He spent all the leisure time that he had browsing Manhattan’s numerous second-hand book shops and sidewalk stalls, amassing a personal library of some 2000 volumes during his three-year stay.

The quest for books led young Ambedkar out of upper Manhattan down to 42nd street on Fifth Avenue, where the imposing beaux-arts styled New York Public Library had recently opened its doors, and opened them to all – including to black people and to women. So impressed was Ambedkar with the public library that upon learning of the death of Sir Pherozeshah Mehta in Bombay, and the Bombay municipality’s plan to prominently erect his statue, Ambedkar shot off a provocative letter from New York to the Bombay Chronicle, the English-language weekly that Mehta had himself launched in 1910. Ambedkar, fresh from another inspiring visit to the New York Public Library, argued in his letter that erecting a public library in Bombay instead of a ‘trivial and unbecoming’ statue would be a far better tribute to the memory of this great man:

It is unfortunate that we have not as yet realized the value of the library as an institution in the growth and advancement of a society. But this is not the place to dilate upon its virtues. That an enlightened public as that of Bombay should have suffered so long to be without an up-to-date public library is nothing short of disgrace and the earlier we make amends for it the better. There are some private libraries in Bombay operating independently by themselves. If these ill-managed concerns be mobilized into one building, built out of the Sir P.M. Mehta memorial fund and called after him, the city of Bombay shall have achieved both these purposes.

It is unfortunate that we have not as yet realized the value of the library as an institution in the growth and advancement of a society. But this is not the place to dilate upon its virtues. That an enlightened public as that of Bombay should have suffered so long to be without an up-to-date public library is nothing short of disgrace and the earlier we make amends for it the better. There are some private libraries in Bombay operating independently by themselves. If these ill-managed concerns be mobilized into one building, built out of the Sir P.M. Mehta memorial fund and called after him, the city of Bombay shall have achieved both these purposes.

The week following Pherozeshah Mehta’s death in Bombay, Booker T. Washington died in Tuskegee, Alabama. Washington, who had been born into slavery, was the most prominent Southern black activist of his day. As Principal of the Tuskegee Institute and author of a best-selling autobiography, Up From Slavery, Washington’s work and writings would have been well known to Ambedkar. Indeed, he would have heard his name prior to reaching America given that his patron, Maharaja Sayajirao Gaikwad, had long before taken to referring to the great social reformer Jotirao Phule, author of Gulamgiri (or, Slavery) as ‘India’s Booker T. Washington’.

The streets of upper Manhattan were beginning to buzz with a new black consciousness that expressed itself not only socio-politically – as for example with the writings and activism of W.E.B. DuBois and the National Negro Committee (which would soon become the NAACP) – but also aesthetically, with emerging literary, theatrical and musical innovations that would set the stage for the later Harlem Renaissance.

Besides his letter to the Bombay Chronicle, Ambedkar sent off numerous letters to family and friends in India during his stay in New York. The letters show that Ambedkar was as attuned to issues regarding gender as he was to those regarding race. One worth mentioning was addressed to a friend of his father, a retired Jamedar of the Indian army, also from the Mahar caste. In it, he implored the recipient – who was the father of a young girl gaining notoriety for having made it all the way to 4th standard in school, unheard of for a Mahar girl – to preach the idea of education to anyone from their community who was willing to listen to him. Ambedkar wrote that he should continue the education of his daughter, and that the entire community would progress more quickly if males and females were educated side-by-side, with no difference between them.

This letter, too, can be seen to reflect the environment Ambedkar now found himself in. For, alongside the emergence of a new black consciousness, New York City was also buzzing with the tireless activism of suffragists demanding the enfranchisement of women in America. And some of the most dynamic of these suffragists were young Ambedkar’s fellow Columbia classmates – and some, as luck would have it, turned out to be his favourite professors.

This letter, too, can be seen to reflect the environment Ambedkar now found himself in. For, alongside the emergence of a new black consciousness, New York City was also buzzing with the tireless activism of suffragists demanding the enfranchisement of women in America. And some of the most dynamic of these suffragists were young Ambedkar’s fellow Columbia classmates – and some, as luck would have it, turned out to be his favourite professors.

The summer just prior to Ambedkar’s arrival at Columbia, his soon-to-be classmate, Chinese-born Mabel Ping-Hua Lee was one of fifty horse-back suffragettes leading a procession of 10,000 people up Fifth Avenue to Carnegie Hall. Among those marching were Ambedkar’s future philosophy professor John Dewey and his future economics professor Vladimir Simkhovitch. In the spring of 1914, Lee published, in a campus paper, an article entitled ‘The Meaning of Woman Suffrage’, advocating for equality of educational opportunities and the economic liberation of women. In terms identical to those Ambedkar would himself utter frequently in his later speeches, Lee referred to ‘equality of opportunity’ as the essence of ‘democracy’. To her, feminism meant ‘nothing more than the extension of democracy or social justice and equality of opportunities to women’.

Lee, supervised by Simkhovitch, and Ambedkar, supervised by Seligman, were together enrolled in the course leading toward the PhD in economics at Columbia’s Graduate School of Arts and Sciences. Later, Mabel Lee would become the first Chinese woman to earn a doctorate in economics in the United States, just as Ambedkar was one of the first Indians (and certainly the first Dalit) to do so.

Vladimir Simkhovitch, apart from being Lee’s doctoral supervisor, was one of the world’s leading experts in socialist economics and Marxist thought. Ambedkar enrolled in his Econ 114 (Marx and Post-Marxian Socialism), Econ 303 (Seminar on Political Economy), Econ 109 (History of Socialism), Econ 242 (Radicalism and Social Reform), and Econ 119 (Economic History) – that’s five full courses on Marxism and socialism! At least for some of these courses, if not out of wider interest, Ambedkar would have had to have purchased some of Marx’s original writings; books by Marx must have been among the 2000 volumes that he had acquired while in New York. As we will later learn, the vast majority of these 2000 books never made it back with Ambedkar to India. Several of them, such as the writings of John Dewey, Ambedkar subsequently repurchased elsewhere. But curiously, we can find none of Marx’s books among Ambedkar’s extant library. It seems that his later experience with Brahmanical Indian Marxists so soured Ambedkar’s view of Marx that he never even bothered to replace his lost books.

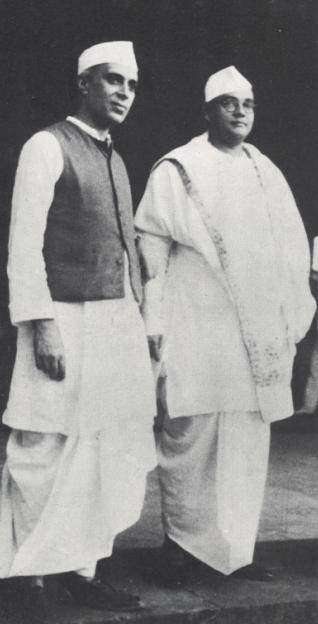

John Dewey (left) and Edwin Seligman (right). Ambedkar’s professors at Columbia University.

One book that Ambedkar purchased in New York that clearly made it with him to India, as apparent from his inscription, was Mrs Rhys Davids’ Buddhism: A Study of the Buddhist Norm (first published in New York in 1912). This book focused on the most ancient, Pali sources of the Buddhist tradition. Ambedkar inscribed the first page in his hand, ‘Columbia Varsity, New York’, and then later on the right-hand side adjacent to it, ‘Bombay, India’. The book and its inscription both show a continuity of his interest in Buddhism, initiated by Dada Keluskar years before.

Of course, Ambedkar’s main focus of study, and the degree toward which he was working, was economics. The study of ancient Buddhism proved useful toward the first iteration of his Master’s thesis, entitled ‘Ancient Indian Commerce’, which may have first been written up as an original research paper for submission as a component of the MA examination. About 75 pages of this manuscript are extant, first covering the trade and commercial relations of ancient India with ancient Egypt, west and east Asia, and then the Greeks and the Romans. Ambedkar strikes a proud, nationalist tone in the work, citing sources to emphasize the superior science, technology and splendours of ancient India over ancient Europe:

It is in the orient, especially in these countries of old civilization, that we must look for industry and riches, for technical ability and artistic productions, as well as for intelligence and science, even before Constantine made [the Roman empire] the centre of political power. Nay, all branches of learning were affected by the spirit of the orient, which was her superior in the extent and precision of its technical knowledge, as well as in the inventive genius and ability of its workman.

It is in the orient, especially in these countries of old civilization, that we must look for industry and riches, for technical ability and artistic productions, as well as for intelligence and science, even before Constantine made [the Roman empire] the centre of political power. Nay, all branches of learning were affected by the spirit of the orient, which was her superior in the extent and precision of its technical knowledge, as well as in the inventive genius and ability of its workman.

Remember that Ambedkar was by now thoroughly familiar with the political, economic, and intellectual history of classical Europe and Ancient Rome, so his claims regarding ancient India’s technical superiority were not merely rhetorical.

‘Ancient Indian Commerce’ then goes on to treat of India’s commercial relations in the Middle Ages, covering industry, trade and commerce throughout the rise of Islam and the expansion of western Europe. The next couple of chapters are missing, and the extant thesis ends with a chapter entitled ‘India on the Eve of the Crown Government’. In this chapter, too, Ambedkar exhibits a fierce nationalism, excoriating British imperialism and taking to task historians of British India who misrepresent the achievements of India prior to the arrival of the British: ‘Not only have they been loud in their denunciation of the Moghul and the Maratha rulers as despots and brigands, they cast slur on the morale of the entire population and their civilization’. What follows are 20 pages of argument and evidence, replete with tables, graphs and charts, of how India systematically contributed to the prosperity of Britain, while itself consistently degenerated, being beaten down and sucked dry.

This tour-de-force of Indian nationalist commercial and economic history then concludes with these damning words:

The supplanters of the Moghuls and the Marathas were persons with no better moral fiber, and the economic condition of India under the so-called native despots was better than what it was under the rule of those who boasted being of superior culture. It is with industries ruined, agriculture overstocked and overtaxed, with productivity too low to bear the high taxes, and with few avenues for display of native capacities, the people of India passed from the rule of the Company to the rule of the Crown.

The supplanters of the Moghuls and the Marathas were persons with no better moral fiber, and the economic condition of India under the so-called native despots was better than what it was under the rule of those who boasted being of superior culture. It is with industries ruined, agriculture overstocked and overtaxed, with productivity too low to bear the high taxes, and with few avenues for display of native capacities, that the people of India passed from the rule of the Company to the rule of the Crown.

American academia was far more accommodating of this magnitude of critique of British imperialism than either British or Indian universities were. Nevertheless, for reasons still unknown to us, Ambedkar abandoned the topic of ancient Indian commerce as his MA thesis, and instead drafted and submitted a much more technical, scope-limited, and positivist text entitled ‘Administration and Finance of the East India Company’. The most likely explanation is that Professor Edwin Seligman had been assigned as Ambedkar’s supervisor, and Seligman was a no-nonsense, technical economist, who viewed the subject of economics as a fact-based, impartial ‘science’. Seligman taught Ambedkar ‘the Science of Finance’, and was averse to the introduction of subjective viewpoints. As Seligman would write 10 years later in a Preface to Ambedkar’s published Ph.D., ‘The value of Mr. Ambedkar’s contribution to this discussion lies in the objective recitation of the facts and the impartial analysis…’.

The officially-submitted thesis, at only 45 pages in length, avoided speaking of history at all (the opening line reads: ‘Without going into the historical development of it…’), and was more restrained in claims regarding the systematic cultural destruction and impoverishment of India by the British. Nevertheless, in the end, Ambedkar exhibits the irrepressibility of his innate need to call out injustice, and closes the thesis with these reproaching words:

It remains, however, to estimate the contribution of England to India. Apparently the immenseness of India’s contribution to England is as astounding as the nothingness of England’s contribution to India….England has added nothing to the stock of gold and silver in India; on the contrary, she has depleted India—‘the sink of the world’.

It remains, however, to estimate the contribution of England to India. Apparently the immenseness of India’s contribution to England is as astounding as the nothingness of England’s contribution to India… England has added nothing to the stock of gold and silver in India; on the contrary, she has depleted India—‘the sink of the world’.

The thesis was accepted by Seligman and passed, and on 02 June 1915 Ambedkar was awarded the degree of Master of Arts in Economics. He had completed the requisite 30 credit hours for the M.A., but 60 credit hours were required for a doctorate. He thus continued in his coursework and in his research and writing, and from that point on, all the credits were counted toward the completion of his Ph.D.

Ambedkar continued working on the ‘science of finance’ as the subject of his doctoral dissertation under Seligman at Columbia. The tentative title for his Ph.D. thesis was ‘The National Dividend of India’, a historical and analytical study of Indian finance. But interestingly, following the award of his M.A. in economics, nearly every course that Ambedkar enrolled in as credit toward his Ph.D. in economics were non-econ courses. After the summer of 1915, Ambedkar took only one economics course (econ 183, on Railways); all of the rest were in languages (French and German), History (4 courses), Philosophy (4 courses), Politics (1 course), and Anthropology (4 courses).

All four of these Anthro courses were taught by Alexander Goldenweiser, himself a student of Franz Boas, the ‘father of American anthropology’. Boas also taught Anthropology at Columbia, in fact he co-taught a course with his friend John Dewey during the same semester that Ambedkar was attending Dewey’s philosophy course. In short, there is no doubt that young Ambedkar was exposed to the modern anthropological method of Boas. One of the primary features of Boas’ approach was his flat rejection of racial typologies which were so popular in late 19th-century anthropology. These racialist theories attributed fixed mental and physical characteristics to specific races. Boas (and indeed Dewey and Goldenweiser) rejected race as the dominant characteristic of a peoples and emphasized far more malleable and conditional characteristics such as culture, history and psychology instead.

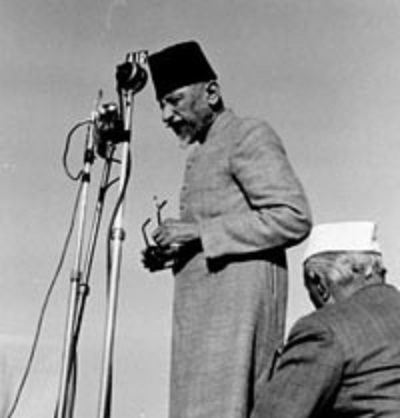

Dr. BR Ambedkar presiding over the joint Columbia Bicentennial – American Alumni Banquet at National Sports Club of India, New Delhi, October 30, 1954. Columbia University.

In May 1916, Ambedkar wrote an extensive and innovative research paper for one of Goldenweiser’s general ethnology courses, where the influence of Boas’ ideas against racial fixity is clear. In addition to opposing a basic Marxist tenet about class antagonism that Ambedkar learned from Simkhovitch’s courses, also discernable within the paper are many echoes of Ambedkar’s everyday experiences regarding race and gender from his wanderings away from campus. In the paper, entitled ‘Castes in India: Their Mechanism, Genesis and Development’, Ambedkar argued that caste was a distinct social category that could not be accounted for either by theories of race or by class antagonism. Rejecting the standard explanation of the racial origins of caste popular in colonial ethnography (i.e. a consequence of Aryan invasions wherein the darker-skinned earlier inhabitants were subjugated) and rejecting the dominant sociological claim that caste was maintained through a hierarchy of purity and pollution, Ambedkar boldly asserted that the essence of caste was the control of women’s sexuality – foremost, the practice of endogamy.

In the paper, entitled ‘Castes in India: Their Mechanism, Genesis and Development’, Ambedkar argued that caste was a distinct social category that could not be accounted for either by theories of race or by class antagonism. Rejecting the standard explanation of the racial origins of caste popular in colonial ethnography (i.e. a consequence of Aryan invasions wherein the darker-skinned earlier inhabitants were subjugated) and rejecting the dominant sociological claim that caste was maintained through a hierarchy of purity and pollution, Ambedkar boldly asserted that the essence of caste was the control of women’s sexuality – foremost, the practice of endogamy.

Ambedkar was exceptionally proud of the work. A year later, it became his first scholarly publication, appearing in the professional journal The Indian Antiquary. Later, when publishing his Ph.D. dissertation as a book, he is described on the title page as the ‘author of Castes in India’. Years later, in 1944, when he was publishing a third edition of his explosive essay Annihilation of Caste, he revealed that the third edition had been delayed for so long after the print run of the 1937 second edition was exhausted because he had been trying to find the time to recast Annihilation of Caste ‘so as to incorporate into it another essay of mine called Castes in India’. Indeed, even Ambedkar’s latest writings from the 1950s, when he was nearing the end of his life, referenced assertions that he had first posited as a young doctoral candidate at Columbia.

In many ways, Ambedkar’s ‘Caste’ paper captured everything other than ‘the science of finance’ that Ambedkar had learned and discovered, both on and off campus, during his three formative years in New York. The formal structure of this rich education was giving shape to his profound lived experiences being Dalit – all of those childhood experiences that he had written about in his autobiographical fragments, Waiting for a Visa – forging an uncommon and unprecedented concatenation of events that helped to make Ambedkar the extraordinary person that he was.

This excerpt has been reproduced with permission from Aakash Singh Rathore from the book Becoming Babasaheb: The Life and Times of Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar: Birth to Mahad (1891-1929) written by Aakash Singh Rathore. All rights reserved. Unauthorised copying is strictly prohibited. You can buy the book here.

ARCHIVE

The Battle of the Somme

Nariman Karkaria

At last, it was our turn to see action, something we had been waiting for with our eyes peeled. Some of the soldiers were very eager to see the Germans in person and flaunt their muscle power, while quite a few were most distressed by the orders to advance forward to the front lines. We were to participate in the Battle of the Somme, which has already achieved legendary status in the Great War.

The Role of the Indian Army

Indian bicycle troops at a crossroads on the Fricourt-Mametz Road, Somme, France. Dated July 1916. From the collection of Imperial War Museums, London.

The Indian Army also took part in the Battle of the Somme.

The Bengal Lancers advanced under heavy fire from the Germans right up to the German trenches and forced them to retreat. On this occasion, our platoon was ordered to advance to the firing line. Our undercover march started at about one o’clock in the night. We had been strictly warned not to utter a single word. With great difficulty, we managed to advance, digging a few trenches and walking all through the night, only to find ourselves in a very unfortunate position in the morning. A German observation balloon which had been flying above us had spotted us, and very soon our route came under heavy fire. Shells were exploding all around us. To escape them, we would lie flat on the ground for a short while before running to advance a little forward. A wave of fear rippled through our platoon. Soldiers were falling all around us with piteous shrieks, but there was nothing that could be done. Each man was on his own and could not be bothered about anybody else. Others would advance by stepping on those injured soldiers who had fallen to the ground. We had no option but to move forward. We also had no idea what kinds of difficulties we were to face as we advanced. Many of our men were lagging behind, but we could not wait for them, and at about twelve noon we reached the famous jungles of Del Ville Wood where we felt we could finally heave a sigh of relief. But fate had other things in store for us. There were no trenches beyond the next twenty-five yards from where we were located. We could not step out of the trenches as we would have been sitting ducks for German guns. The Germans were hardly at any distance from where we were—say about a hundred yards away in their trenches. In spite of this situation, the Commanding Officer gave orders to advance further. We had no option but to run, and we ran in pairs. We would advance about ten steps before throwing ourselves flat on the ground. Our progress did not last very long. Soon enough, the enemy started firing at us with their machine guns.

We were staring death in the eye. But as luck would have it, there had been a fierce battle on this very site just four days ago, and the bodies of dead soldiers were lying all around us. These corpses proved very useful in sheltering us from the enemy gunfire. As we advanced, we would lie behind these corpses, and they would act as our shield taking all the gunfire. Ah, what a terrible experience! Just one bullet and we would also have joined the army of cold corpses!

War in the Skies

After a very desperate battle and the loss of over fifty soldiers, we were lucky enough to be able to take possession of the trenches. Because of the non-stop action during the night and the better part of the day, we had not even had a cup of tea, much less anything to eat. I had managed to eat a couple of biscuits while moving forward. This was all I had had, with which I had to be content for the whole day. Once we took possession of the trenches, the different companies of the platoon were immediately assigned positions. While the A and C Companies were assigned the forward trenches, the B Company was assigned the communication line, which was about ten yards behind us, and the D Company was a further fifteen yards behind them in the support line. We were immediately ordered to make structural improvements in the trenches, which meant more digging. These trenches were not deep enough for a man to stand erect. The soldiers were tired of standing with their backs bent for extended lengths of time. The trenches were also rather narrow and we could hardly move around in them. We began using our small shovels and spades, and started digging at a steady pace, making as little noise as possible. We had hardly started digging when the sky above us was criss-crossed by enemy planes. They had been sent to monitor our progress and signal our position. Soon enough, our lines were bombarded by their artillery positions and we had to suspend our digging operations. Before we go further ahead with our story, let us take a look at the role of these aeroplanes in the war.

These aerial barques would fly high over enemy camps and their trenches, and photograph our positions to determine where the enemy was concentrated and how their lines were positioned. They would then go back and relay all the information to the base. They were, however, most deadly when they worked in conjunction with the artillery. These planes would be assigned to specific batteries; during an assault, these planes would hover above the enemy lines and relay back information on where the shells were landing. If the shells were landing at too short or too long a distance from the enemy trenches, they would immediately ask the battery to adjust its range. If they spotted a shell that had landed at the right place, they would immediately signal a ‘repeat fire’ to completely pulverize the position. Sometimes they would come in huge numbers and we would be carpeted with aerial fire. These aerial barques completely terrorized everybody in the trenches. The minute they appeared above us, we would be ordered to remain as still as possible. If we froze in our positions, it was possible that they might not spot us.

These planes were also mounted with machine guns that would merrily go ‘Bang! Bang!’ and wreak havoc on those below. Occasionally, planes from both the sides would engage each other in the skies, and this was indeed a sight to behold.

To contain these demons of the skies, a different kind of specially designed artillery known as ‘anti-aircraft guns’ would be deployed. They would keep up a relentless fire on the planes from the minute they were spotted.

Storm on a Dark Night

This being our first day in the firing-line trenches, all the soldiers were not assigned specific duties. Some of them were free while others were stationed at specific locations on sentry duty in batches. As these trenches were not deep enough for the soldiers to stand erect and peep over them to monitor the enemy’s movements, a special glass contraption was designed, which could be attached to the tip of the bayonet of one’s gun. This helped the sentry sit down and monitor the space between our trenches and those of the enemy. At short intervals, they would slightly raise their guns very carefully, and peep into the glass and see if there were any enemy advances. Every so often, German snipers would shoot at the bayonets of these soldiers with perfect aim. These German snipers were a real nuisance. At night, snipers from both sides would emerge from the trenches and shoot at the slightest movement. Besides these man-made miseries, we also had to face the fury of nature. In addition to the relentless noise of heavy guns firing through the dark night, we had to brave the most frightful thunder accompanied by incessant rain. It would rain all through the night and the trenches would be flooded. We would be standing in chest-deep water, wondering when the enemy would mount a surprise attack. Even as our boots and clothes were weighed down by the squelching mud and water, our officers would keep braying at us: ‘Beware! The enemy might attack!’ Buffeted from all sides and terrorized by the incessant guns, there were many soldiers who felt it would be far better to emerge from the trenches and take a chance with the enemy gunfire. There were others who were so paralysed by fear that they would appear almost insane and would not stir from their positions. Even if they had to answer nature’s call, they would be unable to take a single step. They would just dig a shallow hole right where they were and do their dirty business. In spite of their paralysis, they were somehow drafted to do some work by the booming orders of the officers. As mentioned earlier, the front line was manned by batches, each batch consisting of one sentry and five soldiers, with a non-commissioned officer in charge of them. They were responsible for holding the front line, and each soldier had to be on strict lookout for one hour at a time. A Lewis gun or a machine gun would be placed between every three batches. If the sentry felt that the enemy was trying to make an advance or if there was the slightest movement detected in the enemy lines, the guns would start firing. These Lewis guns played a very important role in this devastating war. These lightweight guns weighed only twenty-nine pounds and could be easily handled by one man who could move it from place to place, and when ordered, start firing at the rate of four hundred bullets per minute. Each of these guns was equivalent to a hundred rifles. We always had to be prepared at the firing line with all these arrangements.

Tear-Inducing Chilli Bombs

Indian infantry in the trenches, prepared against a gas attack [Fauquissart, France]. Dated 9th August, 1915. From the HD Girdwood collection, British Library.

After spending a miserable night in the trenches, we were shivering in our wet clothes in the morning. Suddenly we were ordered to ‘Stand to!’ Now what was this for? Even as we were wondering what it was all about, a gas that felt like chillies began pervading the trenches. Shrill orders to wear our goggles were urgently issued.

When the gas first attacked us, we could hardly understand what was happening. The gas began to envelop us from every direction and gas shells lobbed from the enemy lines were silently exploding all around us. Our eyes were in a state of extreme irritation. It felt as if they would burst.

We could hardly see anything; tears were flowing freely from our eyes, and it felt dark and terrifying. In spite of all this, everybody got into fighting position, facing the enemy lines and waiting for the inevitable attack. It was generally understood that the enemy released this gas just before it launched an attack. It rendered our soldiers blind and immobile for a brief while, and during this period, they could get the better of us and wrest our trenches. We could hardly open our eyes since the chilli gas had caused our eyes to turn red and swell up. How was a soldier to fight under such adverse circumstances? Along with this chilli gas, regular artillery fire was also kept up by the enemy, which further exacerbated the situation. To combat the nuisance of these ‘tear shells’ and to protect the eyes, a special kind of protective spectacles had been designed. They were made of ordinary glass through which everything could be seen, and the frame was fringed with flannel which ensured that the gas did not make contact with the eyes. The only saving grace was that exposure to tear gas, unlike poison gas, was not fatal; it merely left you blind for a short while.

On a Starvation Diet

Besides all the problems described above, we had yet another major problem to contend with: how to silence our hunger pangs. Soldiers on the firing line had to remain awake day and night and had no chance to lie down. To make matters worse, they had to scrounge for food. Admittedly, there was a lot of food dumped beyond the support lines as the motor transport guys would weave through the heaviest artillery fire to supply the food. Transporting the food from the dump to the firing lines was a major challenge for the soldiers. They would step out in large numbers to bring the food stuffed in small gunny bags back from the dump to the front line. The extreme conditions in the trenches, what with them being flooded with rainwater and slush, and the incessant firing of the enemy many a time prevented them from returning safely. They would be injured and fall down en route, and the food would also lie rotting there. The situation at the firing line was indeed desperate. The D Company had been assigned the support line and was responsible for supplying us with food, but as they came under heavy fire, they could not venture out of their trenches. Even though we were at the very front, the lines immediately to our rear suffered the most, bearing the brunt of the artillery fire. At least fifteen to twenty men from one company would get injured every day, and the condition of the injured was indeed very pitiable. How was food to reach us under this situation? We had to subsist on the few packets of biscuits and bully beef we had carried with us. Where was the question of getting a hot cup of tea? Not a single wisp of smoke was supposed to escape from the trenches. If the enemy spotted smoke coming from a trench, they would consider it to be a live target and fire immediately. The poor soldiers would go scrounging around for cigarette stubs.

Such was the dire situation at the front lines—starvation, mud and slush—and the relentless artillery fire had so harassed the soldiers that they were a pathetic sight to behold.

They had not shaved for days. How do you think they looked? It is best left to the imagination!

Our Final Assault

King George V inspecting Indian troops attached to the Royal Garrison Artillery, at Le Cateau on 2 December 1918. Imperial War Museums, London.

This was to be our last day at the famous Del Ville Wood. After many days of suffering and troubles, would it be too much to say that our imminent relief seemed like a new lease of life to us? Early in the morning, the news had already spread in the trenches that we were to be relieved tonight; our faces were aglow with delight. Just after noon, more authoritative news reached us, which was slightly different. We were indeed to be relieved, but we would have to perform some more arduous tasks tonight; the soldiers welcomed this news as a means of getting out of the trenches. All of us had been eagerly looking forward to being relieved for many days. Instead of spending yet another day in the slushy trenches, it was more preferable to emerge from them and show our courage in hand-to-hand combat. As per the orders issued to us, we were to launch our attack at ten in the night. Two companies were to lead the attack while the other two companies were to support us in the assault, and the trenches which we were to evacuate were to be occupied by the 4th Suffolk Regiment. All preparations had been made for a full-on artillery assault at the same time. Some of the soldiers were eagerly looking forward to the hour of the assault, while the colour had drained out of the faces of others. This supposedly minor assault was sure to claim the lives of many soldiers, but nobody knew who it would be. As things turned out, luck was on our side on this dark and evil night. It was pitch dark and the rain was falling steadily, and the roads were so slushy that they were of a porridge-like consistency. The enemy might have felt that there was very little likelihood of an attack from us in such awful weather. Our strategy was to attack under the cover of bad weather. Every minute seemed like an hour. As we waited, we could hear our hearts beating within our chests. After a seemingly eternal wait, it was finally the dark hour when we were to launch our attack. Just as orders were barked out to get us ready for the final assault, a volley of artillery fire passed over our heads towards the enemy lines. Within the blink of an eye, the Germans returned fire. Hundreds of shells were exploding loudly all around us. Their smoke darkened the skies, and we were already so scared that any enthusiasm we might have had for escaping from the trenches evaporated. Before we could think any further, orders were screamed out: ‘Over the top! Best to luck!’ The minute we heard the orders, we jumped out of the trenches and emerged into the open. We could soon hear the plaintive screams of our fellow soldiers, many of whom had fallen victim to the fire from the mortars and the machine guns. The rest of us braves, mindless of the fate of our colleagues, kept advancing. Lying flat on the ground, we crawled for over an hour and were lucky enough to finally make it to the enemy front lines. We then lobbed small bombs into their trenches and soon jumped into the trenches for a face-to-face duel. At this stage, many soldiers lost their lives to close-range enemy bullets, while some were bayoneted to death. We were able to take ten prisoners and capture one machine gun. We were about to turn back but heavy enemy artillery fire prevented us from doing so.

This was the heaviest bombardment I had ever seen, with thousands of shells exploding simultaneously all around us.

Because of the rain, mud and slush, our clothes felt like they weighed a ton. Dragging all this paraphernalia with us, a few of us were lucky enough to get back to our lines. Even as we were luxuriating in our good fortune, Lady Luck finally deserted us. A heavy shell landed just ten yards from where we were and exploded very loudly; we tried to jump away from it, but were not lucky enough to escape without being hit. I was also hit by a fragment. Even though I jumped as quickly as I could into a trench, my leg was injured in a gruesome manner. This had to happen just on the very last day when we were about to be relieved from trench duty. When fate turns against you, there is nothing you can do!

Adding Insult to Injury

Like me, there were hundreds of injured soldiers moaning and lying unattended in the trenches.

There was nobody to listen to our groans or pay any attention to us. Our troubles were just starting. If you managed to reach the dressing station, your troubles could come to an end. But in this bloody battle, it seemed like an impossibility. It was routine for hundreds of soldiers to get injured every day, and each platoon had its own stretcher-bearers who were supported by men from the Royal Army Medical Corps. For this assault, special working parties had also been formed. The firing and the destruction was, however, so severe that all these arrangements came to nought. Unlucky soldiers with stomach or leg injuries would frequently die a painful death in the trenches. If an injured soldier managed to drag himself away from the action, he stood a better chance of survival. Once you reached the dressing station, you would be one among thousands of injured soldiers crying for medical attention. The best possible care was given to them. There would be trolleys and vehicles from the Ambulance Corps to take them to the casualty clearing station. Once you reached this location, you could safely assume that your troubles had come to an end. All it needed was a cup of hot tea to make the injured soldier feel much better. After the seemingly endless days of nightmarish existence starving in the trenches, a cup of tea and the ministrations of female nurses felt like heaven. And then it was ‘Back for Blighty!’

This excerpt has been reproduced in arrangement with Harper Collins Publishers India Private Limited from the book The First World War Adventures of Nariman Karkaria: A Memoir written by Nariman Karkaria and translated by Murali Ranganathan. All rights reserved. Unauthorised copying is strictly prohibited. You can buy the book here.

ARCHIVE

Contesting Power – Contesting Memories: the Obelisk at Koregaon

The obelisk at Koregaon is characterised by a surprising commemorative history. A memorial to a bloody encounter within an imperial war, this monument provides a case study which illustrates that contestations of memories often bear the imprint of contestations for hegemony that are played out in the present.

The obelisk at Koregaon in Western India, built as a demonstration of empire builders’ belief in their own power and military prowess, serves a similar function today, but for a different group of people: the former Untouchables who had collaborated with the colonizers against what they perceived as a tyrannical indigenous regime.

The recently emerged tradition of an annual pilgrimage to the memorial, should be seen as an effort at creating and popularizing an alternative culture of the former Untouchables, now known as Neo-Buddhists. While Indian society grapples with the problem of accepting the equality of its various castes, one can witness different pathologies of memory surrounding the monument. Today, both amnesia and pseudomnesia are associated with the Koregaon memorial, defying the locus of a person in the discourse on social justice in present-day India. The memorial had faded into oblivion from British public memory long before the end of the imperial rule. However, it has undergone a metamorphosis of commemoration and now signifies something quite different from what was originally intended.

The Battle of Koregaon and its Memorial

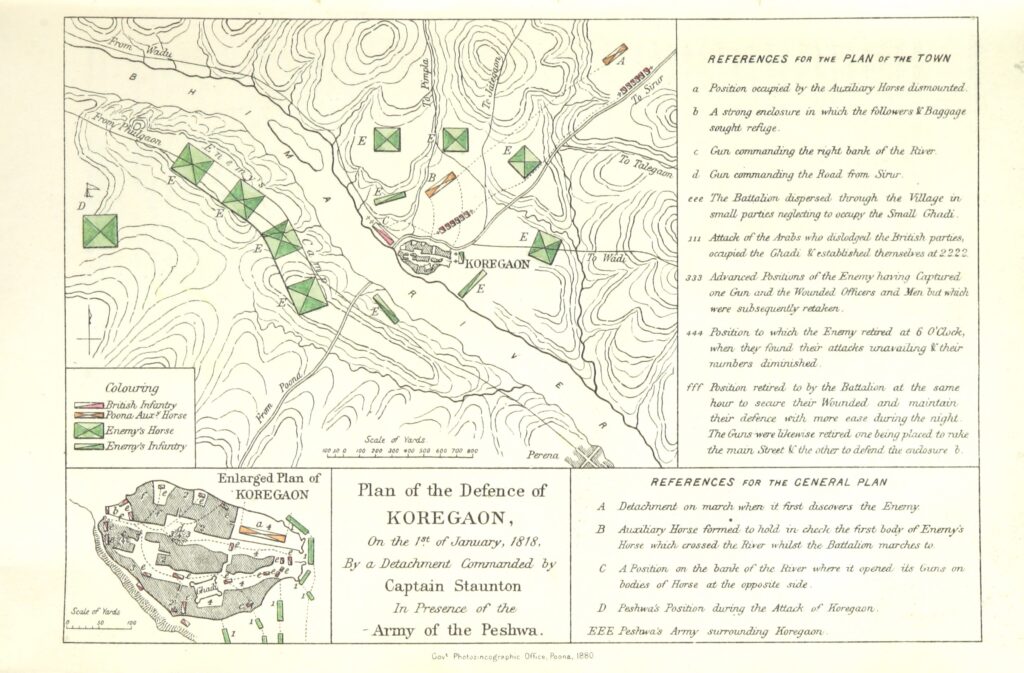

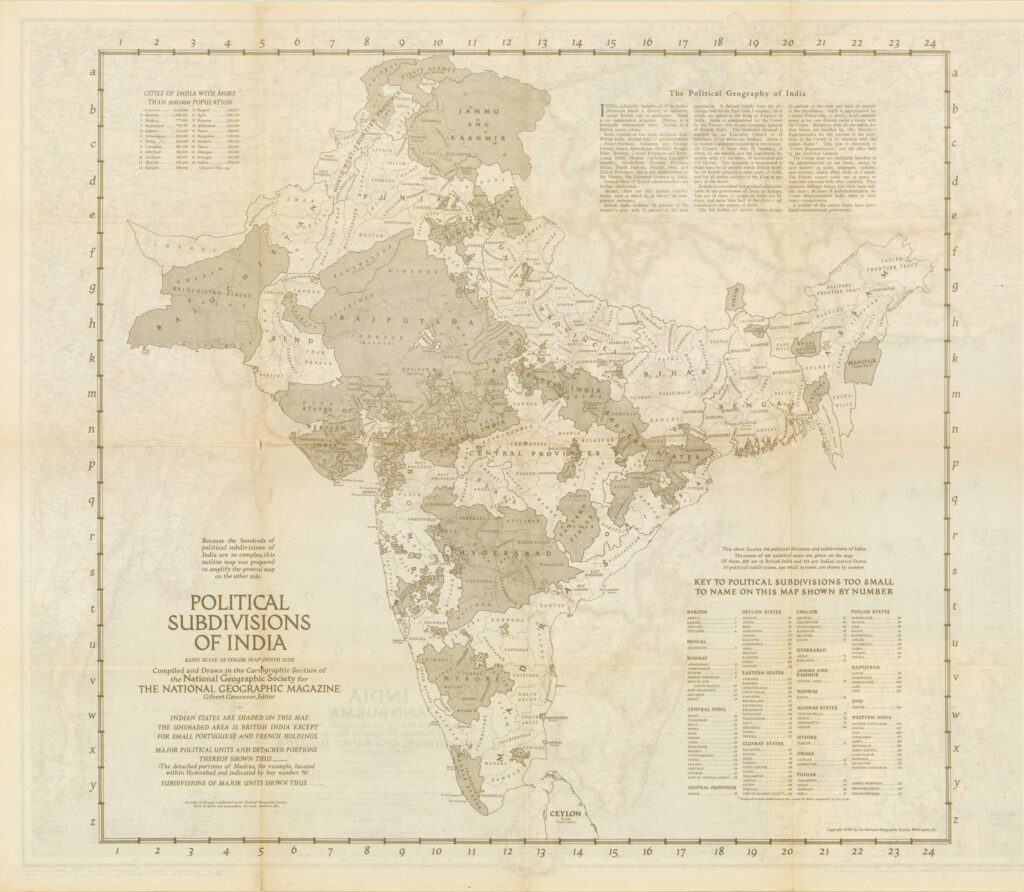

British defence plan during the Battle of Koregaon from Gazetteer of the Bombay Presidency (Ed). Sir James M. Campbell, p. 259. Published in 1896. British Library.

The political ascendancy of the British East India Company in Eastern and Northern parts of India dates back to the battle of Plassey in 1757. From then on it gradually began extending its political hold to the other parts of India. During the same period, from their base in Pune in Western India, the Peshwa rulers (1707-1818) were also extending their political influence. Clashes between the Peshwas and the Company seemed inevitable. On 1 January 1818, a battalion of about 900 Company soldiers, led by F. F. Staunton from Seroor to Pune, suddenly faced a 20,000-strong army commanded by the Peshwa himself. The encounter took place at the village of Koregaon on the banks of the river Bheema. In the words of Grant Duff, a contemporary official and historian, “Captain Staunton was destitute of provisions, and this detachment, already fatigued from want of rest and a long night march, now, under a burning sun, without food or water, began a struggle as trying as ever was maintained by the British in India.” The battle was not decisively won by either side, but in spite of heavy casualties, Staunton’s outnumbered troops managed to recover their guns and carry the wounded officers and men back to Seroor.

As it was one of the last battles of the Anglo-Maratha wars, which ended with a complete victory of the Company, the encounter quickly came to be remembered as a triumph. The East India Company wasted no time in showering recognition on its soldiers.

While Staunton was promoted to the honorary post of aide de camp by the Governor General, the battle received special mention in Parliamentary debates next year. A memorial was commissioned and a year later, Lt Col Delamin, who was passing by the village, could already witness the construction of a 60-foot commemorative obelisk.

The Koregaon memorial still stands intact today. It is supposed to commemorate the British and Indian soldiers who ‘defended the village with so much success’ when the British East India Company confronted the Peshwa army in a ‘desperate engagement’. Marble plaques adorn the four sides of the obelisk. The two plaques in English are accompanied by translations into the local Marathi language. The Memorial Plaque declares that the obelisk is meant to commemorate the defence of Koregaon wherein Captain Staunton and his corps “accomplished one of the proudest triumphs of the British army in the East.” Soon after, the word ‘Corregaum’ and the obelisk were chosen to adorn the official insignia of the Regiment. In the Parliamentary debates in March 1819, the events were described as follows. “In the end, they not only secured an unmolested retreat, but they carried off their wounded!” In his volume published in 1844, Charles MacFarlane quotes from an official report to the Governor calling the engagement “one of the most brilliant affairs ever achieved by any army in which the European and Native soldiers displayed the most noble devotion and the most romantic bravery.” Twenty years later, Henry Morris confidently added: “Captain Staunton returned to Seroor, which he entered with colours flying and drums beating, after one of the most gallant actions ever fought by the English in India.” Later chroniclers of colonial rule continued to shower praise on the plucky Company force for displaying “the most noble devotion and most romantic bravery under the pressure of thirst and hunger almost beyond human endurance.” In 1885, even the ‘Grey River Argus’, a newspaper published in far-off New Zealand, described the battle in glowing terms. After the turn of the century, though, the colonial commemoration began to fade and gradually the event slipped from Britain’s public memory. The battle is now only mentioned in specialized literature on military history as an example not of British martial capabilities, but of that of the Sepoys.

Memories: ‘Ours’ and ‘Theirs’

Today the memorial finds itself just off a busy highway toll booth – a common site in the post-globalisation Indian landscape. Every New Year Day, the urban middle classes who need to use the highway, remind each other to avoid the particular stretch of the highway that passes by the memorial. Their reason for doing so is that “those people would be swarming their site at Koregaon.” Indeed, the memorial has become a site of pilgrimage attracting thousands of people who gather there every 1 January. If one asks the pilgrims what brings them together, there is a clear answer.

“We are here to remember that our Mahar forefathers fought bravely and brought down the unjust Peshwa rule. Dr Ambedkar has started this pilgrimage. He asked us to fight injustice. We have come to take inspiration from the brave soldiers and Dr Ambedkar’s memories.”

Initially, one might be baffled by this admiration for the native soldiers who fought on the British side and lost their lives in a fight against their own countrymen. A careful scrutiny of the list of casualties inscribed on the memorial reveals, however, that twenty-two names from amongst the native casualties listed end with the suffix “-nac”: Essnac, Rynac, Gunnac. The suffix ‘-nac’ was used exclusively by the untouchables of the Mahar caste who served as soldiers. This observation becomes particularly relevant when considered within the context of the caste profile of the Peshwas, who were orthodox and high-caste Brahmin rulers. The story of Koregaon is thus not just about a straightforward struggle between a colonial and a native power. There is another important but largely ignored dimension to it: caste.

Peshwa Bajirao II, who fought at the Battle of Koregaon. Coloured lithograph, Chitrashala Press, Poona, 1888. Wellcome Collection.

The Peshwas, Brahmin rulers of Western India, were infamous for their high caste orthodoxy and their persecution of the untouchables. Numerous sources document in great detail that under the Peshwa rulers, the ‘untouchable’ people who were born in certain so-called low castes were given harsher punishments than high-caste people for the same crimes. They were forbidden to move in public spaces in the mornings and evenings lest their long shadows defile high-caste people on the streets. Besides physical mobility, occupational and social mobility were also denied to these people who formed a major part of the population. Human sacrifices of ‘untouchable’ people were not uncommon under these eighteenth century rulers who had framed elaborate rules and mechanisms to ensure that the untouchables stayed just as their name suggests – untouchable. In 1855, Mukta Salave, a 15-year-old girl from the untouchable Mang caste who attended the first native school for girls in Pune, wrote an animated piece about the atrocities faced by her caste:

‘Let that religion, where only one person is privileged and the rest are deprived, perish from the earth and let it never enter our minds to be proud of such a religion. These people drove us, the poor mangs and mahars, away from our own lands, which they occupied to build large mansions. And that was not all. They regularly used to make the mangs and mahars drink oil mixed with red lead and then buried them in the foundations of their mansions, thus wiping out generation after generation of these poor people. Under Bajirao’s rule, if any mang or mahar happened to pass in front of the gymnasium, they cut off his head and used it to play “bat ball,” with their swords as bats and his head as a ball, on the grounds.’

Peshwa atrocities against the low-caste people have remained ingrained in public memory to this very day.

When the East India Company began recruiting soldiers for the Bombay Army, the untouchables seized the opportunity and enlisted. Military service was perceived as a means to opening the doors of economic as well as social emancipation. Political freedom and nationalism had little meaning for a population who had to choose between a life where the best meal on offer was a dead buffalo in the village and a life where their human dignity was respected – not to mention a decent monthly payment in cash.

While the untouchable soldiers fought on the British side against their own countrymen, the valour they showed is not at all perceived as a shameful memory today. In fact, Koregaon has become an iconic site for the former untouchables as it serves as a reminder of the bravery and strength shown by their ancestors – the very virtues that the caste system claimed they lacked. The memories related to the Koregaon memorial, help to explain how a memorial of colonial victory built in the early nineteenth century has been adapted to serve as a site that gives inspiration to the formerly untouchable people of India.

Mahars and the Military

Throughout much of the nineteenth century, the battle of Koregaon and the memorial were warmly remembered amongst military, imperial and political circles in Britain. At the beginning of the twentieth century, though, British rule was firmly established all over India, and the Koregaon Memorial faded from mainstream commemorative practices. Neither Britain at the height of colonial glory, nor India, which was beginning to receive small doses of independence, had time to commemorate the violent struggle of the days of the Honourable Company. Other lines of tradition were broken, too. The Mahar regiment had continued to demonstrate its bravery and loyalty in the battles of Kathiawad (1826) and Multan (1846). But then, in spite of the low castes’ long-standing military alliance with the British, some Sepoys from the Mahar Regiment, which formed a part of the Bombay Army, joined the “Indian Mutiny” in 1857. This added to a certain reluctance the British had always shown at the enlistment of Mahars. Subsequently, they were declared to be a non-martial race and their recruitment was stopped in May 1892.

Once their recruitment was discontinued, the Mahars soon began to feel the pinch. Gopal Baba Valangkar, a retired army-man founded a ‘Society for Removing the Problems of Non-Aryans.’ In 1894 the members of this society sent a petition to the Governor of Bombay to remind him that the Mahars had fought for the British to acquire their present dominion over India and requested a reconsideration of the decision to exclude Mahars from the Martial races, which deprived them of entry into the military service. The petition was rejected in 1896.

Another leader of the untouchables, Shivram Janba Kamble made an even more sustained effort to achieve the emancipation of the Untouchables. He had been involved in the work of the ‘Depressed Classes Mission’ which ran schools for untouchable children. In October 1910, R. A. Lamb of the Bombay Governor’s Executive Council was invited as the chief guest for a prize-giving ceremony in one of these schools. In his speech, Lamb mentioned his annual visits to the Koregaon Memorial. He drew attention to the ‘many names of Mahars who fell wounded or dead fighting bravely side by side with Europeans and with Indians who were not outcastes’ and regretted that ‘one avenue to honourable work had been closed to these people.’ It is not known whether it was Lamb’s speech that put the Koregaon Memorial back into the limelight or whether it had remained in living memory.

His words certainly lent weight to the argument that it was the Mahars who fought for the British and made them ‘masters of Poona.’

Within the first two decades of the twentieth century, Kamble organised a number of meetings of the Mahar people at the memorial site. In 1910, he arranged a grand Conference of the Deccan Mahars from 51 villages in Western India. The Conference sent an appeal to the Secretary of State demanding their ‘inalienable rights as British subjects from the British Government.’ They made a strong case for letting Mahars re-enter the army and argued that the Mahars were ‘not essentially inferior to any of our Indian fellow-subjects.’ Up until 1916 this request was repeated by various gatherings of untouchables in Western India. As the First World War gathered momentum, the Bombay government eventually issued orders in 1917 providing for the formation of two platoons of Mahars.

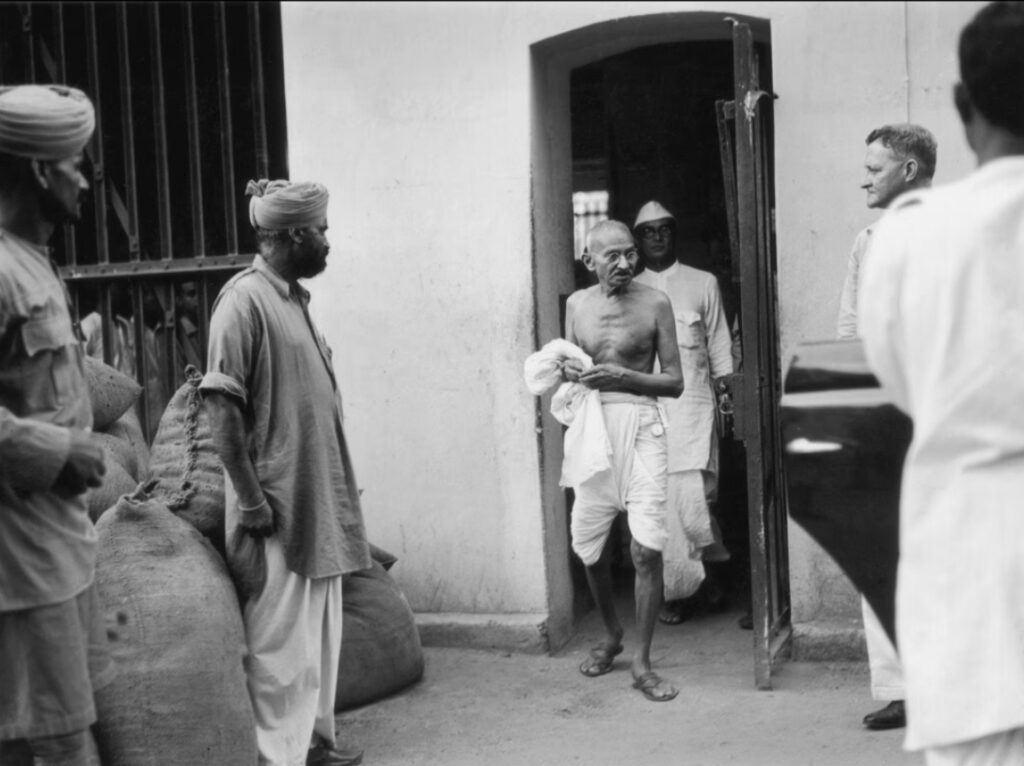

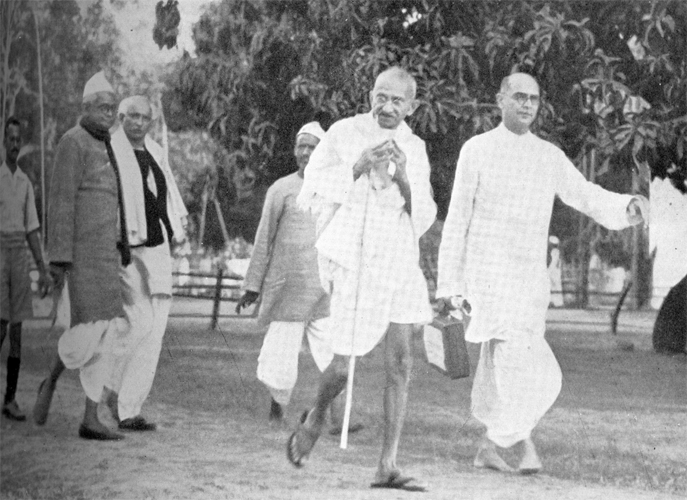

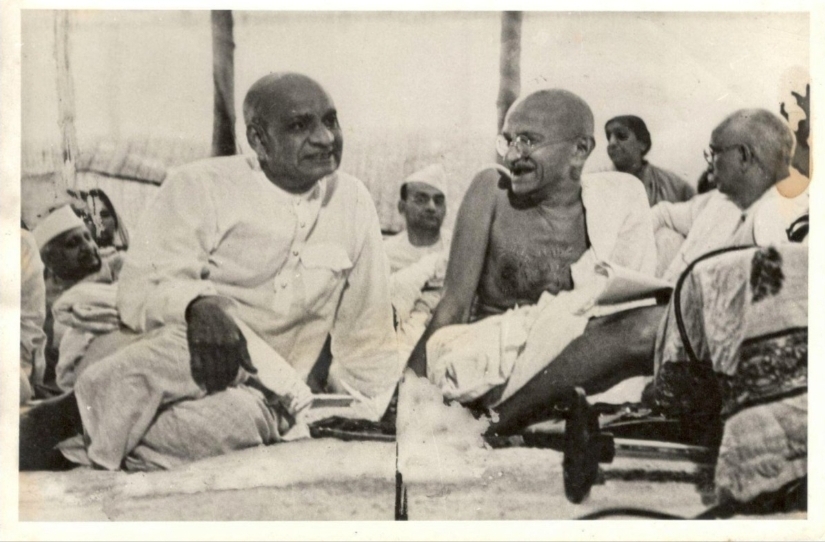

The Coming of Ambedkar

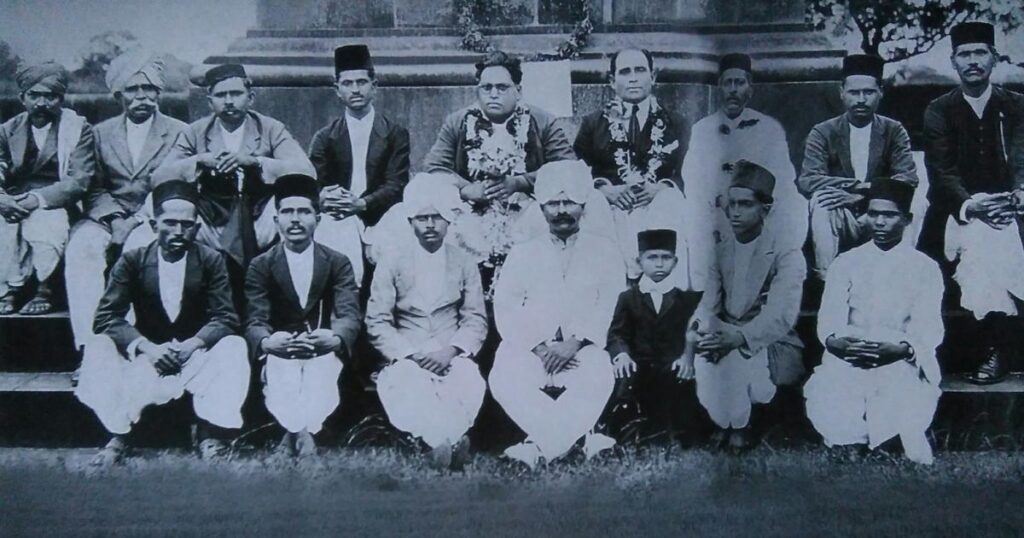

The happiness of the Mahars was, however, short-lived. Recruitment was stopped as soon as the war ended. This led to a renewed campaign for recognizing the valour of the Untouchables. By then, the demand had long since assumed the level of a movement for the general emancipation of the Untouchables. Within this campaign the Koregaon Memorial had become a focal point. Various meetings were held at the obelisk during which Kamble and other leaders invariably reminded the Untouchables of the valour and prowess exhibited by their forefathers. On the anniversary of the Koregaon battle on 1 January 1927, Kamble invited Dr Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar to address the gathering of Untouchables. Ambedkar was not merely another leader of the untouchables. He was by now, as far as Indian politics was concerned, a force to be reckoned with.

Ambedkar was born in 1891, the son of a retired army subhedar from the Mahar caste. In spite of his first-hand experience of caste-based discrimination, he attained a doctorate from Columbia University, a D. Sc. from London School of Economics and was called to the Bar at Gray’s Inn by the age of 32. In 1926, he became a member of the Bombay Legislative Assembly.

He could not fail to appreciate the significance of the memorial for advancing the cause of the emancipation of the Untouchables. Not only did he make an inspiring speech at the gathering, he also supported the idea of reviving the memory of the valour of the forefathers by an annual pilgrimage to the site on the anniversary of the battle.

As a representative of the Untouchables, he was invited by the British to the Round Table Conference in 1931 where the future of the Indian Nation was to be decided. Based on his arguments at the conference, he wrote a small treatise called The Untouchables and the Pax Britannica in which he referred to the Koregaon battle to support his argument that the Untouchables had been instrumental in the establishment and consolidation of British power in India.

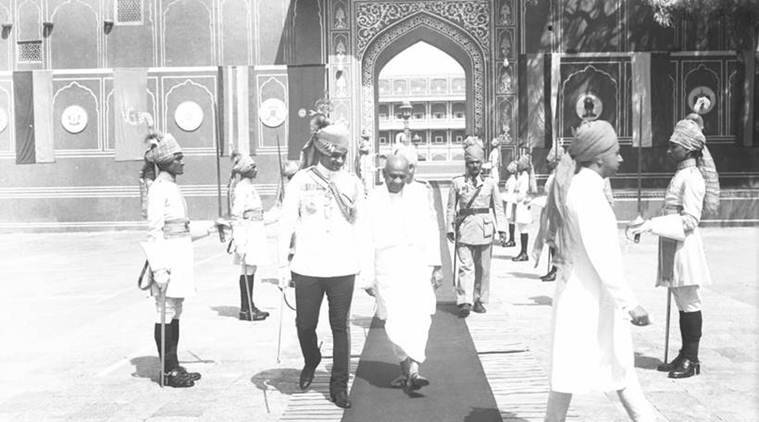

BR Ambedkar and his followers at the Koregaon victory pillar on 28 December 1927. Wikimedia Commons.

Indian mainstream politics from the 1920s until 1947 is recognised as the Gandhian era. Gandhi, having been born in the middle order caste of traders, had a different outlook on the systemic exploitation of the Untouchables on the basis of caste. He called the Untouchables Harijans, meaning people of God. Ambedkar and his followers resented both this name and the patronising attitude behind it. Underlying this surface issue, there were major ideological differences between Ambedkar and Gandhi. For the India represented by Gandhi and the Indian National Congress, the primary contradiction was that between colonial supremacy and Indians’ aspirations for political freedom. For Ambedkar and the Untouchable masses he represented, the oppression was not primarily located in the political system but arose from the socio-economic sphere. There was a clash of interests. The Indian National Congress under Gandhi sought to represent all Indians in a unified front against the colonial rule. Although Ambedkar was, unlike some “sections of Dalits and non-Brahmans who believed that colonial rule had been an unambiguous liberating force”, by no means a staunch supporter of British rule, he had quite a different new India in mind. While Gandhi saw the ideal social order arising from a reformed Hinduism, Ambedkar sought “political representation independent of the Hindu community.” In 1930, Gandhi embarked upon the Civil Disobedience Movement against the systems and institutions of the colonial rule. Kamble and a few other representatives of the depressed classes retaliated by launching what they called the “Indian National Anti-Revolutionary Party”. Its manifesto was quoted in The Bombay Chronicle:

In view of the fact that Mr Gandhi, Dictator of the Indian National Congress has declared a civil disobedience movement before doing his utmost to secure temple entry for the “depressed” classes and the complete removal of “untouchability”, it has been decided to organise the Indian National Anti-Revolutionary Party in order to persuade Gandhiji and his followers to postpone their civil disobedience agitation and to join whole-heartedly the Anti-Untouchability movement as it is… the root cause of India’s downfall…. The Party will regard British rule as absolutely necessary until the complete removal of untouchability…

Though this party did not attract much support in mainstream politics, it demonstrates that for the Untouchables, social and economic well-being was of greater and more immediate concern than political freedom, and hence colonial rule was regarded as a possibly necessary evil for the time being. It also shows that there were other and often contradictory voices in the independence movement of India. These have often been glossed over in nationalist rhetoric.

A New Memory

India won her independence in 1947, and Ambedkar chaired the committee tasked with the drafting of the new constitution. The ‘annihilation of caste’, however, remained a distant dream. The Hindu Code Bill proposed by Ambedkar in order to bring about extensive reforms in the Hindu socio-cultural scene was not accepted by parliament. In 1951 a disillusioned Ambedkar resigned from the Cabinet. Five years later, under his leadership, millions of Untouchables converted en masse to Buddhism in a step towards attaining total freedom from exploitation. The same year, after Ambedkar’s death, a political party, called the Republican Party of India, was formed to represent the interests of the low-caste people.

The conversion opened the floodgates for cultural conflicts with the high castes. The immediate reaction of the Hindu right was one of denial. The strategy of cultural appropriation that has worked so well for Hinduism from the times of the Buddha is employed even today to project the Buddhists as just another sect within Hinduism.

For the neo-Buddhists, this necessitated the creation of new and different cultural practices. Amongst the neo-Buddhists in western India one of the invented cultural practices that emerged as a result is the pilgrimage to the Koregaon Memorial. Thousands of neo-Buddhists throng to the memorial every New Year’s Day to commemorate the valour of the Mahars who helped to overthrow the high caste rule of the Peshwa. They also commemorate the visit of their leader, Dr. Ambedkar, on 1st January 1927.

Unlike any Hindu pilgrimage site, the Koregaon memorial is devoid of the tell-tale signs of a holy marketplace. No sellers of garlands and sweets and images of Gods are to be found here. It is a deserted place all through the year. However, come New Year, the place is dotted with little stalls selling books, cassettes and compact disks. Various publishers of Ambedkarite literature set up their stalls of books. Neo-Buddhist songs are played loudly in the stalls extolling the greatness of Ambedkar and emphasizing the need to change the world. Leaders of the now numerous factions of the Republican Party of India address their followers. Neo-Buddhist families visit the memorial obelisk. They offer flowers or light candles. An important part of the ritual is to offer a Vandana, a recital of verses from Buddhist texts.

An equally important element of their ritualised behaviour is the buying of books. Interviews with various booksellers have shown a surprising fact: whenever there is a gathering or a pilgrimage of the neo-Buddhists, the bookstalls do roaring business. It may be interesting to note that the average length of books sold at these stalls is short – volumes of 30-70 pages priced between 10 to 50 rupees. It might be an indication of the fact that the readers may be neo-literate, have very little time to spend on reading and can only afford cheaper books. Many publishers of related literature have indicated that their daily sales figures at the Koregaon pilgrimage and other such important pilgrimages (eg. Mumbai and Nagpur) often exceed their sales figures for the rest of the year. It could be perceived as an indication of the belief in emancipatory potential of education among the neo-Buddhists, especially of the former Mahar caste. Some of the best-selling titles include Marathi translations of books authored by Ambedkar himself, eg. Buddha and His Dhamma, Annihilation of Caste, Who Were the Shudras? Other popular books include Dalit autobiographies. They also sell Dalit poetry and small biographies of Dalit leaders.

These books offer a Dalit perspective on Indian history wherein colonial rule is portrayed as instrumental for emancipation, even though it remained ignorant of realities of caste exploitation. Jotirao Phule and Ambedkar are among the prominent Dalit writers who propounded this view of the colonial rule in which Gandhi and the movement for India’s independence do not figure very positively. The fact that Ambedkar chaired the Committee that created the Indian Constitution in 1950, however, is considered supremely important. Any attempt to criticise or seek a change in the Indian Constitution, therefore, provokes fierce opposition from the Dalit population. The anti-corruption movement led by Anna Hazare and his team in 2011 is a recent example. The extra-constitutional structure to create a powerful ombudsman (Lokpal) for resolving the issues of corruption was not welcomed by Dalit leaders and public.

The Importance of Forgetting

Though the Koregaon Memorial was constructed by the Colonial rulers, it does not feature on the commemorative landscape of today’s British public. This amnesia might be attributed to the fact that the colonial memories, especially of violent battles are no longer the object of pride in present-day Britain. This amnesia is matched by the high castes in India. Poona, the capital of Peshwas has become a software and education city called Pune. When a sample of 130 members of the high caste, newly rich people (who have come to be nicknamed as Computer Coolies) were asked about the Koregaon memorial, none of them knew what it was.

Elite amnesia is not total, though. There are also, what may be called conflicting memories. During the 1970s the Western Indian state of Maharashtra witnessed a spate of popular (a)historical novels topping the best-seller lists in Marathi. Many of them dominate the historical understanding and perceptions of the Marathi-speaking middle classes even today. Two important novels from this genre, both authored by Brahmins, describe the battle of Koregaon in passing. Mantravegla by N. S. Inamdar is based on the life of the Last Peshwa. It claims that the battle was, in fact, won by the Peshwas. Recently, this trend of creating alternative memories about the Peshwa battles has become even stronger. The battle of Panipat, which saw a complete defeat of the Peshwa armies in 1761, is commemorated today by high-sounding rallies. The kind of rhetoric used during these rallies suggests that it was the Peshwa who won the battle.

The Koregaon Memorial occupies a very significant place in today’s neo-Buddhist culture. The internet and other electronic media are used to document and commemorate the Koregaon battle and Ambedkar’s visit to it. An image search for Koregaon Pillar yields hundreds of digital pictures of the Memorial Obelisk. Film clips are available on Youtube. At least a dozen blogs in English and Marathi have entries related to the Koregaon memorial. They describe the battle and the role of the Mahar soldiers and also remind the readers about what the Untouchables could achieve if they show the resolve.

Conclusion

The obelisk of Koregaon Bheema is thus a site which has generated conflicting memories. These memories represent the divergent interests of the groups involved in their creation. Those wishing to commemorate the greatness of the Peshwa rule – the symbol of high caste supremacy – either choose to ignore the Koregaon battle, or create a Pseudomnesia of Peshwa victory. While the obelisk marks an imperial site of memory that is largely forgotten in the homeland of the empire, the monument has undergone a metamorphosis of commemoration in Western India.

It no longer reminds the public of imperial power, but for the former Untouchables whose forefathers fought at Koregaon it serves the purpose of providing “historical evidence” of the ability of the Untouchables to overthrow the high caste oppression.

Considering the fact that Indian society is still dominated by the system of caste hierarchy, the Koregaon Memorial is also a reminder that present-day contestation for hegemony is often manifested in contesting memories.

This paper has been carried out courtesy with the permission of Shraddha Kumbhojkar. It has been presented without its abstract, citations, footnotes and bibliography for purposes of easier reading.

The paper has also been published in Sites of Imperial Memory, (ed.) Dominik Geppert, Frank Lorenz Muller, Manchester University Press, Manchester, New York, 2015. as Politics, Caste and the remembrance of the Raj: the Obelisk at Koregaon. You can buy the book here.

ARCHIVE

Hinduism: Major Schools other than Bhakti

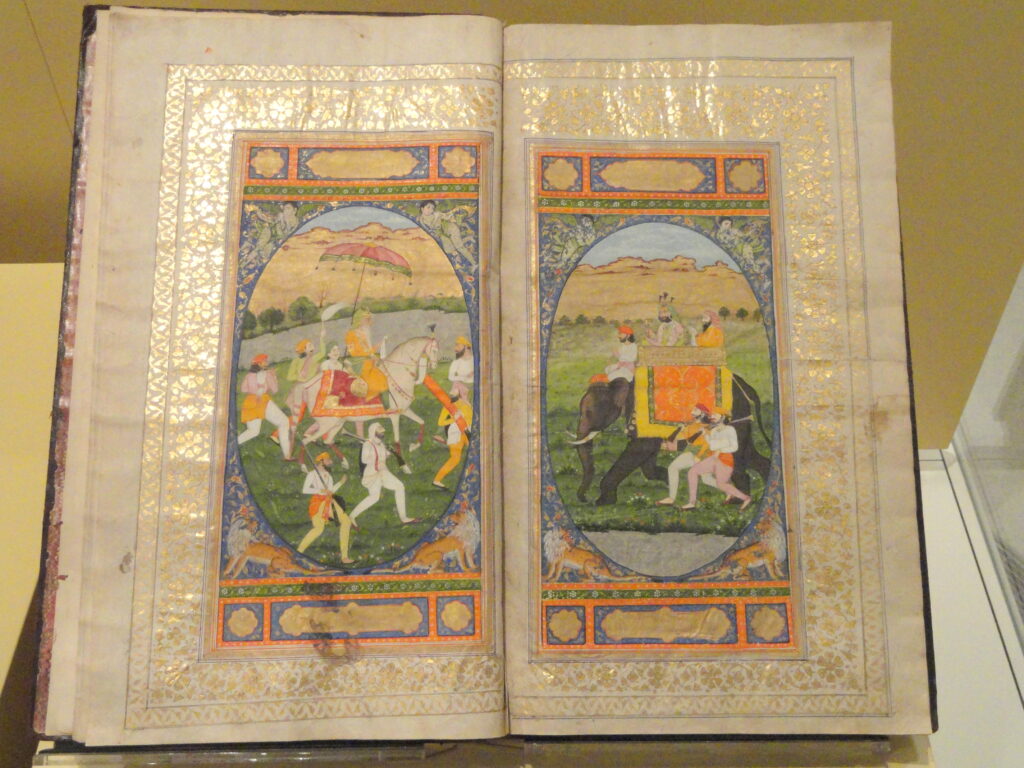

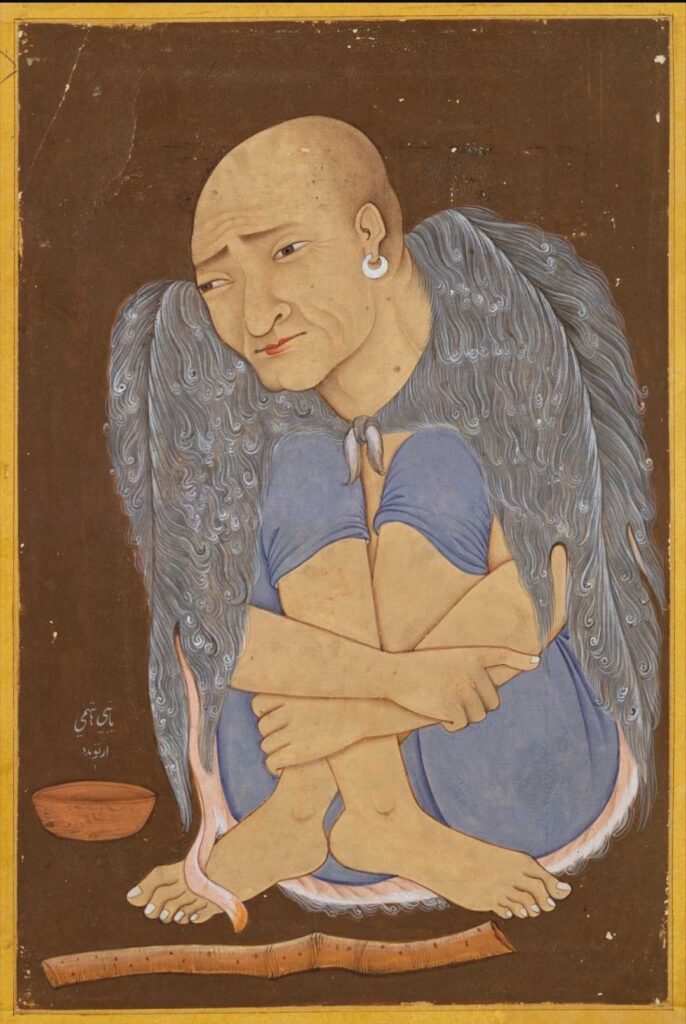

On a first view the continuing coexistence of Hinduism and Islam seems to be the most significant aspect of religious life in Mughal India. This very observation, however, tends to obscure the fact that Hinduism and Islam were not religions in the same sense. In his remarkable work on the religions of the world, the anonymous author of the Dabistan (written, c.1653), notes that “among the Hindus there are numerous religions, and countless faiths and customs.” In other words, while “Hindu” was the appellation of an Indian who was not a Muslim, it was yet difficult to speak of Hinduism as a single body of doctrine in the same sense as one could speak of Islam or, indeed, of the Semitic religions in general. It was equally true, however, that, having developed in mutual interaction and expressed in a large part in the same language (Sanskrit), the different sects of Hinduism yet shared the same idiom and even the same or similar deities. Written sixty years earlier, Abu’l Fazl’s A’in-i Akbarī (1595) precedes the Dabistan in giving us a very detailed and comprehensive description of Hindu beliefs.

On a first view the continuing coexistence of Hinduism and Islam seems to be the most significant aspect of religious life in Mughal India. This very observation, however, tends to obscure the fact that Hinduism and Islam were not religions in the same sense.

The Mughal period witnessed a continuing assertion in Brahmanical texts of almost all the basic elements of Higher or Orthodox Hinduism that the Ain-i Akbarī and the Dabistan outline. There was a notable exposition of Mimamsa in Narayana Bhatta’s Manameyodaya (c.1600). The school upheld the automatic functioning of the system of transmigration of souls in life-cycles, the station in each life being the result of deeds (karma) in the previous cycles. The author of the Dabistan makes the interesting observation that the “common belief” among the Hindus was that though there was one Creator, the created beings in their lives remained bound by the influence of their own deeds. The emphasis on karma was now the key to dharma, or prescribed conduct of the smriti schools. In this field the traditional doctrine continued to be reasserted in digests, commentaries and elaborations. Vachaspati (c.1510) wrote the Vivädachintamani in Mithila (Bihar). In Bengal, c.1567, Raghunandana of Navadvip wrote his twenty-eight treatises, the Smrititattva, which became an authority on ritual and inheritance. The Nirnayasindhu of Kamalakara Bhatta (1612), which cites Raghunandana as an authority, in turn, obtained legal and religious authority in Maharashtra. An encyclopedic legal work, the Viramitrodaya was compiled by Mitra Mishra under the patronage of Bir Singh, a leading noble of Emperor Jahangir (1605-27).

Ain-i-Akbari

![]() These works did not generally make any noteworthy deviations from positions adopted in respect of the supremacy of the Brahmans and the caste-rules as defined by the earlier Smritis. If anything, they repeated and elaborated the restrictions imposed on the lower castes and women. Raghunandana went so far as to declare that the Brahmanas were the only ‘twice-born’ left, since, according to him, the Kshatriyas and Vaishyas had by now fallen among the ranks of the Shudras!

These works did not generally make any noteworthy deviations from positions adopted in respect of the supremacy of the Brahmans and the caste-rules as defined by the earlier Smritis. If anything, they repeated and elaborated the restrictions imposed on the lower castes and women. Raghunandana went so far as to declare that the Brahmanas were the only ‘twice-born’ left, since, according to him, the Kshatriyas and Vaishyas had by now fallen among the ranks of the Shudras!

In Vedanta, the Shankaracharya tradition was influential enough to produce a number of texts. It is clear from various statements in the Dabistan that the pantheism of Shankaracharya had by the mid-seventeenth century permeated a large number of sects and schools. Sadananda in his Vedantasära (c.1500) exhibits an admixture of Samkhya principles. On the other hand, Vijñänabhikshu (c.1650), author of the Samkhyasara, admitted the truth of Vedanta, professing to see the Samkhya Duality as no more than one aspect of the Truth. A similar reconciliation of Vedanta with Shaivite beliefs seems to have been developed by Appayya Dikshita (1520-92) of Vellore, a prolific writer on many subjects. A Shaivite theologian of the south of a later phase was Shivananar (fl.1785).

Commensurate with the widespread currency of Tantrik beliefs and practices reported by the Dabistan, Tantrik literature received considerable additions during this period. Mahidhara of Varanasi wrote the Mantra-mahodadhi in 1589. In Bengal Pürnända (fl. 1571) wrote treatises on philosophy and magical rites; in the next century Krishnänanda Agamavägisha of Navadvip wrote the authoritative textbook, Tantrasara.

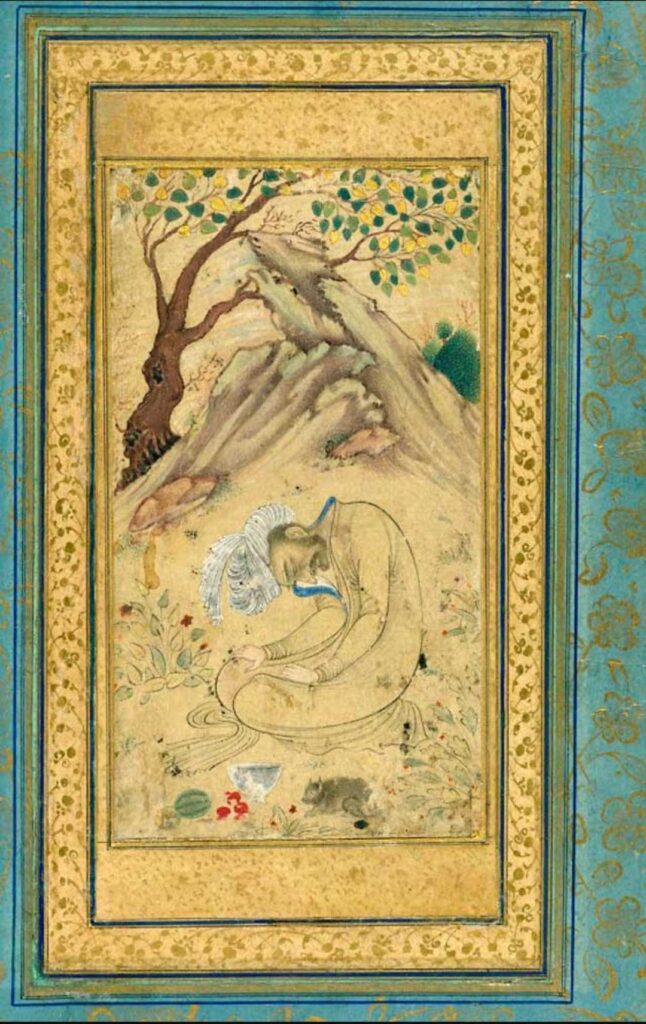

Bhakti Sects

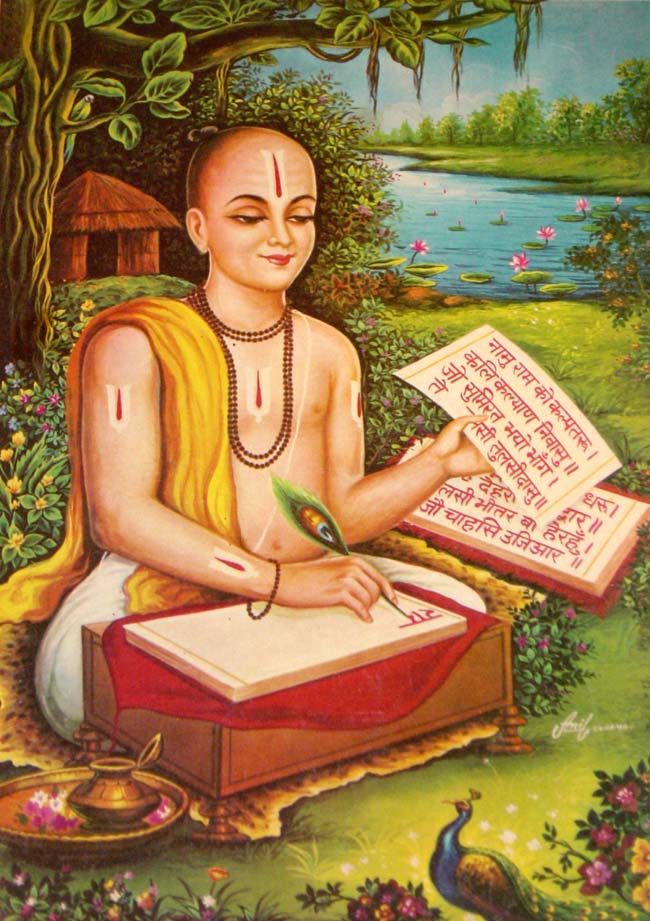

The sixteenth and seventeenth centuries were, however, essentially the centuries of Vaishnavism. In the Northern India the Rama cult had its greatest propagator in Tulsidas who in his Ramcharitmanas, written in the Awadhi dialect, gave a popular garb to the original Rāmāyaṇa. Tulsidas was a firm believer in the dharmashastra, and he regarded the popular monotheistic cults, with their Shudra leaders, as signs of the degradation of the present age (kalijug). Yet this was not the main message of his work. In his fervent verses of devotion and portrayal of a just Rama, the incarnated deity became God, in full control of destiny.

The sixteenth and seventeenth centuries were, however, essentially the centuries of Vaishnavism.

The expression was still more emotional when the object of bhakti (devotion) was Krishna, another incarnation of Vishnu. Chaitanya (1485-1533), a Brahman priest of Navadvip (Bengal) initiated a cult of Krishna and his female lover Radhā, in which the devotee, repeating the deity’s name, pictured himself as a companion of Krishna at Vrindaban, re-enacting in his mind His “manifest” sports (lilas). These mental visions were the means of a communion with the Lord, in which Krishna too relished the devotee’s love. While Chaitanya had his followers mainly in Bengal, he left very active successors, the gosvamins, at Vrindaban near Mathura, who in a series of Sanskrit works gave a philosophical basis to the cult and outlined its ritual. To his followers Chaitanya himself appeared as a joint incarnation of Krishna and Radha. Though in their life as householders, the devotees followed the caste ritual, the right of worship was not denied to the lower classes; and the Sahajiya sect (eighteenth century) rejected life as ordained by the smritis and introduced shaktik and tantrik practices. In Assam, a Vaishnava sect paralleling that of Chaitanya was founded by a junior contemporary of his, Shankaradeva (d.1568), who however avoided image-worship and emphasized an Absolute, Personal God, to Whom all devotion directed in the form of love for Krishna.

Vallabhacharya (d.1531) and his son Vitthalnath (d.1576) propagated a religion of grace (pushtimarga); and Surdās, owing allegiance to this sect, wrote Sur-saravali (1545) in the local language, Braj, in which the sports of Krishna with Radhā and others were described as manifestations of the Lord’s supreme powers. The sect obtained some popularity in Gujarat and Rajasthan; there developed an excessive adoration of the descendants of Vallabhacharya (now regarded as an incarnation of Krishna), who obtained the designation ‘Mahārāj’, and relied on the following of a rich mercantile community. The Rädha vallabhis owed their foundation to Hita Harivamsha (d.1553) and assigned to Radha the more crucial position in the Duality of Divinity.

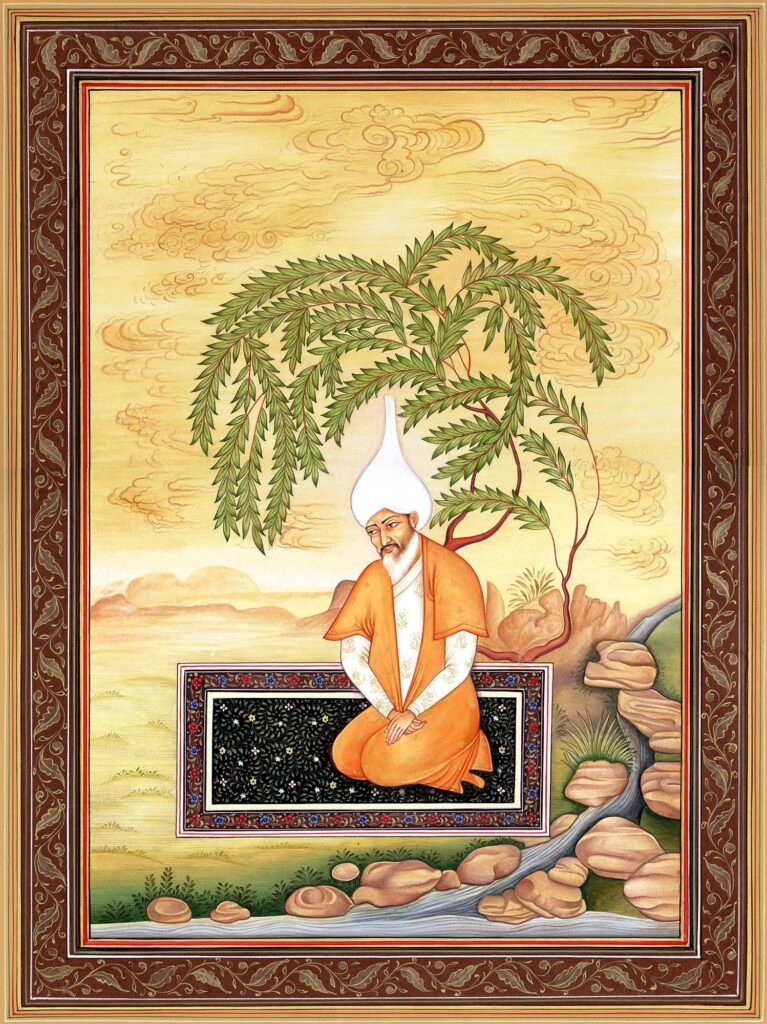

Tulsidas composing his famous Avadhi Ramcharitmanas (Wikipedia Commons)

The Vaishnavite movement in Maharashtra contained both Unitarian and conservative elements. Eknath (d.1599), a Brahman, expounded the principle of bhakti and allowed all castes as well as women to assemble and praise the Lord and join in the ecstasy of devotional chants (kirtan). He also tended to discount mere ritual. Tukārām, (d.1649), a Shūdra peasant, might possibly have been influenced by the Chaitanya sect yet while addressing himself to Vithoba, the Lord of Pandhari, his God (Vitthal) tends to be closer to the Ram of the monotheist Kabir than to the Krishna of Chaintaya. He sings of the possibility of recourse to God by a devotee, howsoever lowly in status, and does not hesitate to use the word Allah for his God. Quite different in approach was his junior contemporary, Rāmdās (d.1681), who combined the propagation of the worship of Rama as God with the upholding of the dharma (“the Maharashtra Dharma”), i.e. maintenance of “the holiness of the Brahmans and deities”. He organized maths or centres of ascetics, and was patronized by Shivaji, the Maratha ruler (d.1680),

In Karnataka, the Dāsakūta movement seems formally to have belonged to Madhvächärya’s system. It originated with Shripadaraya (d.1492), but was mainly spread by his disciple Vyasaraya (d.1539). The songs of the sect in Kannada show attachment to Viththala, the deity of Pandharpur, and yet revel in an ecstasy of devotion which recalls Chaitanya. A disciple of Vyasaraya, Kanakadas was a shepherd (Kurub) and in his popular compositions insisted on the lowly to the Lord.

Other Sects; Jainism

Logic and dialectics (nyaya and tarka) continued to attract attention through the compilation of commentaries and text-books. The Navadvip schools produced Raghunātha Siromani’s commentary (c.1500) on Gañgesha; and on this commentary Gadhādara (c.1700) in turn commented. Shañkara Mishra in Upaskära (c.1600) commented on the Nyāya-sütra. Among textbooks, Annam Bhațța wrote Tarkasamgraha (c.1585) and Jagadisha, the Tarkamyita (c.1700). A.B. Keith comments unfavorably on the obscurity and scholasticism of this literature; he also notes that all the schools were now “fully theistic”.

The survival of the materialist ideas of the Chārvākas, described in the Dabistān as constituting the ninth tradition within Hinduism, is of considerable interest. The Chārvākas believed that only the world perceived by the senses was real; “whether one becomes high or low results from the nature of the world”, and not from divine direction. The existence of a Creator or of gods was denied, and so also the truth of the Vedas. A number of specific criticisms by them of the beliefs in the miraculous and divine are quoted; possibly these circulated by word of mouth or are derived from the texts of opponents, for our author does not name any text or votary of the sect for his source.