What can we learn from the political cartoons of Ambedkar in English dailies published between the 1930s and 1950s and why are they important?

With this question in mind, we bring to you a short excerpt from No Laughing Matter: the Ambedkar Cartoons 1932-1956 by Unnamati Syama Sundar. The book presents a selection of 124 contemporaneous political cartoons on Dr. Ambedkar which were selected by the author from the archives of leading English newspapers. Each cartoon is followed by two sections, the first detailing the context of the selected cartoon, and the second titled ‘Scratching the Surface’ records the author’s critical response to each cartoon.

The archival research required for this project was conducted over a number of years while the author studied toward his Ph.D. at JNU’s School of Arts and Aesthetics.

The book broadly covers six periods when Dr. Ambedkar was covered by the English language press. Namely; (1930s) during his exchanges with Gandhi around the Poona Pact, (1942-1943) while working as the labour member in the Viceroy’s Executive Council, (1944-1946) when he was trying to secure Dalit representation in Independent India (1947-1948) while working on the Indian Constitution, (1950-1951) for his work on the Hindu Code Bill and lastly (1953-1956) when Dr. Ambedkar was considering leaving Hinduism.

The author in the introduction notes the mandate of this volume as “not to address this serious gap in academic literature on cartooning, nor does it offer an exhaustive index of all the archival cartoons pertaining to Ambedkar. The task for me is more a political imperative than a research agenda.” The author hopes to highlight how humour in the form of political cartoons is not free of ideological inclinations. And, if not critically created, can end up serving the dominant discourse of caste in India instead of ridiculing power.

This is important because we popularly imagine political cartooning to deflate claims made by power, and don’t usually characterise them as replicating structures of power. Foucault in The Order of Things: An Archaeology of the Human Sciences writes, “In any given culture and at any given moment, there is always only one épistémè that defines the conditions of possibility of all knowledge, whether expressed in a theory or silently invested in a practice.” This épistémè in India comes from an upper-caste understanding of the world and what they consider valuable knowledge or action. While the political cartoons themselves critique everyday politics, their understanding of these events arguably comes from this casteist épistémè that undergirds what is understood as humorous or what tropes are relied on to critique the everyday. To give a real-world example of how this process works, in white-collar spaces in India being asked to do menial/demeaning work by a boss leads to a retort – ‘Main uska naukar hun kya’ – am I his servant? This retort, which acts as an argument highlighting the nature of this menial or demeaning work, can also highlight how in Indian society marginalised groups such as Dalits are usually forced to do this kind of work every day. The dignity of labour is only afforded to upper-caste white-collar workers.

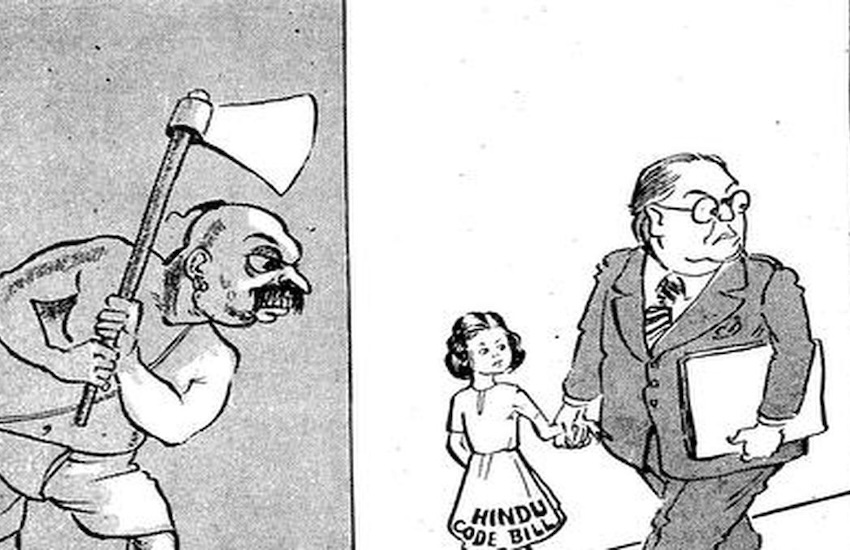

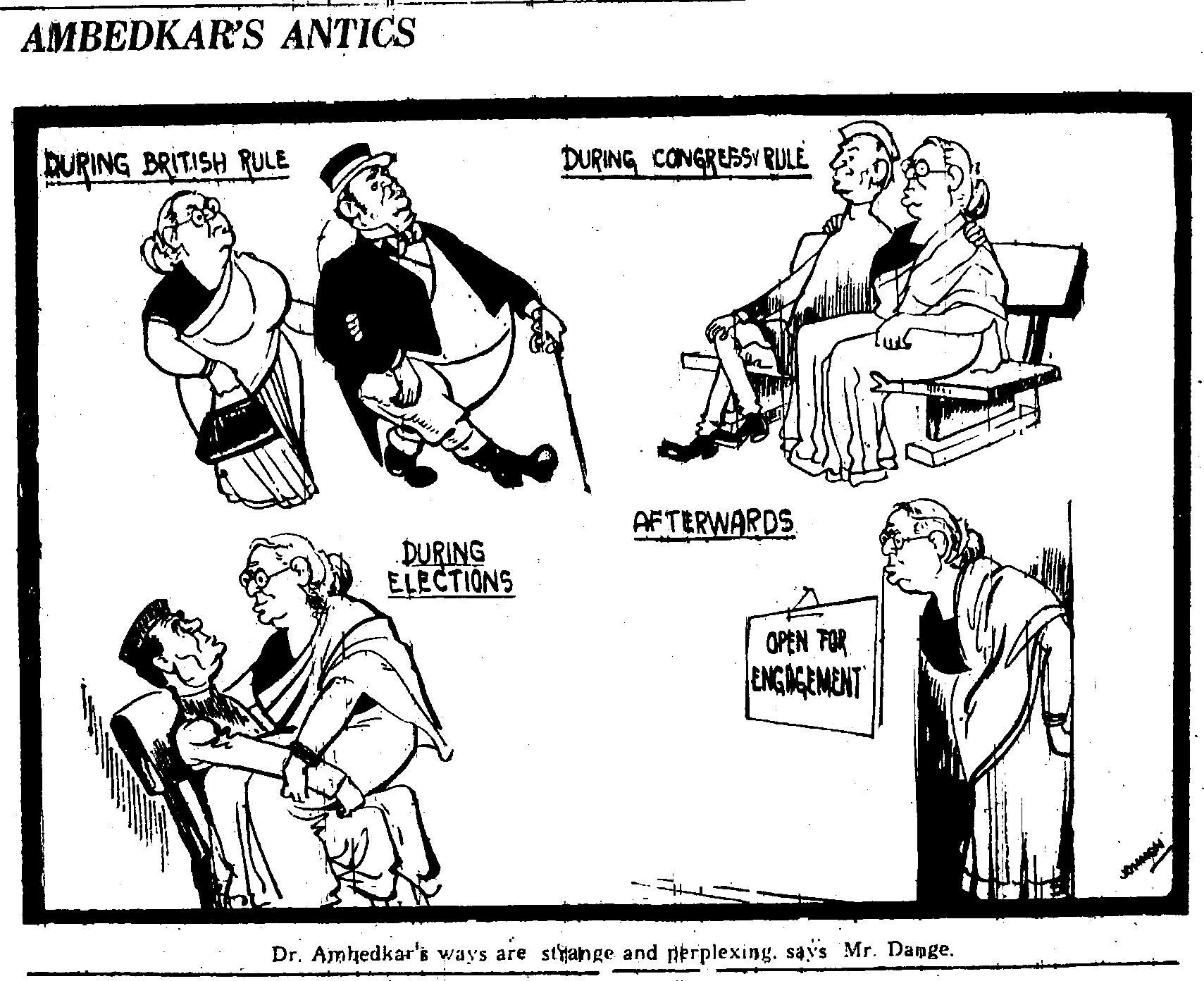

Coming back to the cartoons, in the mid-twentieth century and to this day, caste and misogyny condition what knowledge and how humour is produced. To illustrate this point we only have to look at how Dr. Ambedkar is caricatured in many of the cartoons in the book. He is either depicted as a ‘loose’ opportunistic woman, a diminutive person when face-to-face with upper-caste leaders, or a child (infantilising Dalits has long been a casteist trope) while asserting his views. In rare cases where he is presented as a regular-sized adult, he is illustrated as a follower of an upper-caste leader. This can be seen in the excerpted cartoon below titled ‘Quenching the Torch’, where Dr. Ambedkar is seen assisting Nehru in ‘quenching’ the Torch of Freedom by bringing in the First Amendment which added more grounds to restrict freedom of speech.

The three cartoons presented below span from 1947 to 1951, largely while Dr. Ambedkar was the head of the drafting committee of the Constitution and then later the Law and Justice Minister in the first cabinet of Independent India.

To support the work of the author and Navayana, please click on the jacket cover at the end of the excerpt to purchase the book.

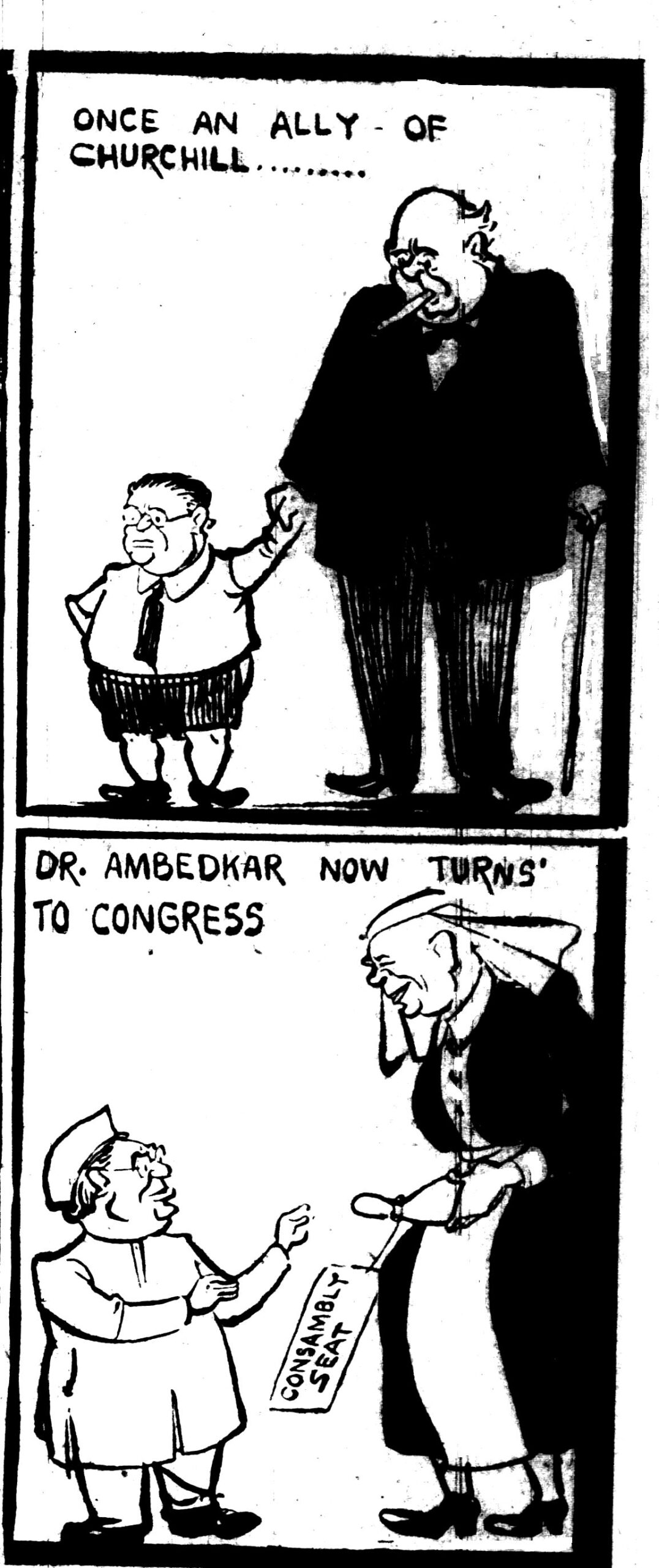

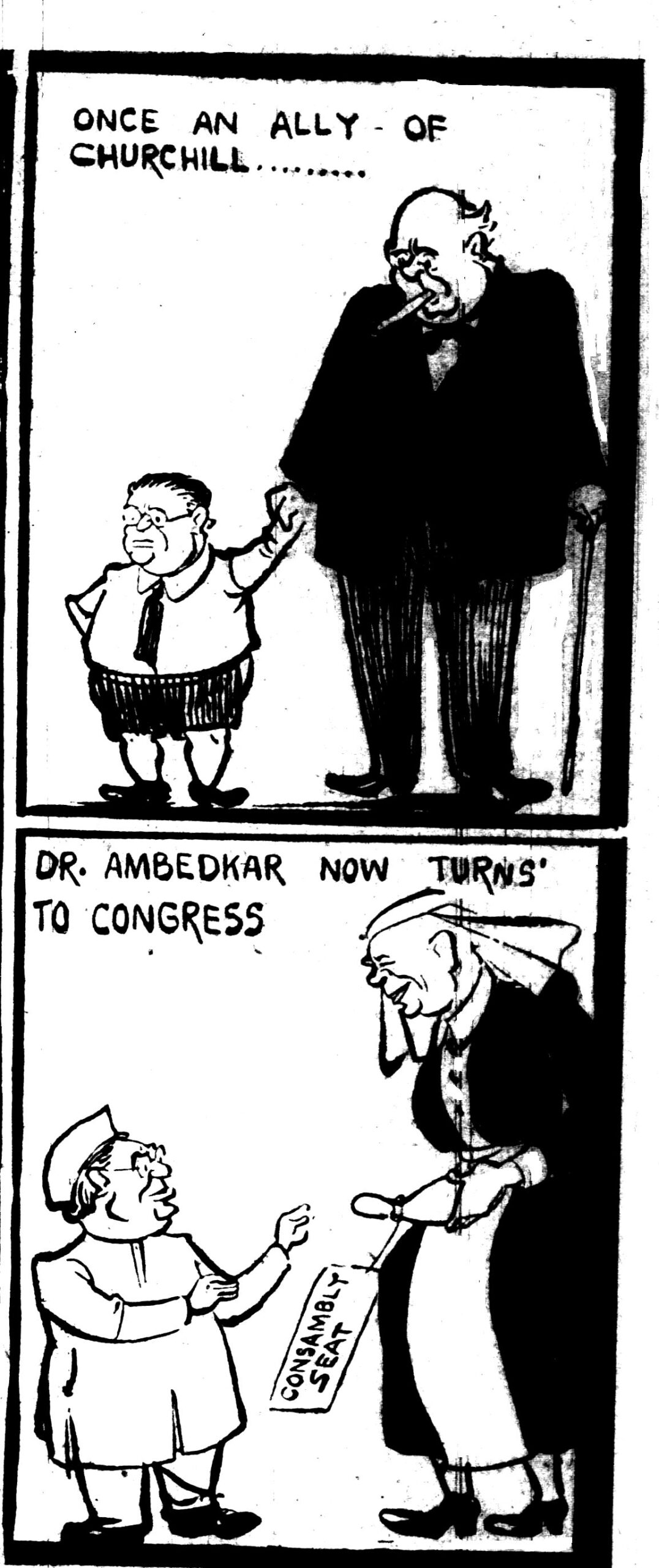

Allied powers

Leader, 6 July 1947, Oommen.

A certain thaw in Ambedkar’s relationship with the Congress happened late in 1946, when the former delivered a speech to the Constituent Assembly warning them about the dangers of drafting a constitution without consulting the Muslim League. The Congress had in the same year fought vehemently against Ambedkar in the Assembly election in Bombay to deny him entry into the body. However, thanks to Jogendranath Mandal’s help in alliance with the Muslim League-he managed to get elected from Bengal. The aforementioned speech came at a critical juncture when Congress leaders were raring to consolidate their power without considering the loss of life this would cause.

Appealing to their reason and emotional make-up, Ambedkar convinced them to keep the negotiations going. He also earned their grudging respect, which was essential because at that moment the Congress held all the cards. This meant that Ambedkar was able to get himself into several committees which sat in adjudication of the future of the new-born nation. His erudition, foresight and level-headedness quickly made him an important part of the proceedings.

With the passing of the Indian Independence Act in British parliament, the leader once again hit troubled waters. Bengal was partitioned, and he was one of many members who lost their seats in the Constituent Assembly. However, this time around, the Bombay Legislative Assembly—which had earlier blocked him—chose to nominate Ambedkar back into the house to fill the vacant seat of M.R. Jayakar, who had recently resigned. Soon, Nehru would call on Ambedkar to take up the post of minister of law in the new cabinet, with a promise of being appointed to the department of planning or development in the future.

Scratching the surface

After his desperate bid to involve Churchill in the struggle to ensure Scheduled Caste rights in free India, Ambedkar had faced an embargo from both the British and Indian leadership. Nevertheless, it is strange that the cartoonist thinks the Congress was doing him a favour by inducting him into the Constituent Assembly. The savarna folks were in over their heads, and needed an able and knowledgeable lawyer to write them their Constitution. What’s more, they could pass off the gesture as benevolence and inclusiveness while at the same time solving their problem of skill and talent. This is a centuries-old tradition.

The cartoonist takes delight in first having Ambedkar appear in an incongruous boxers-and-tie outfit, and then showing him give it up for the Congress cap and Nehru-style kurta-pyjama: but he remains stunted, never growing up.

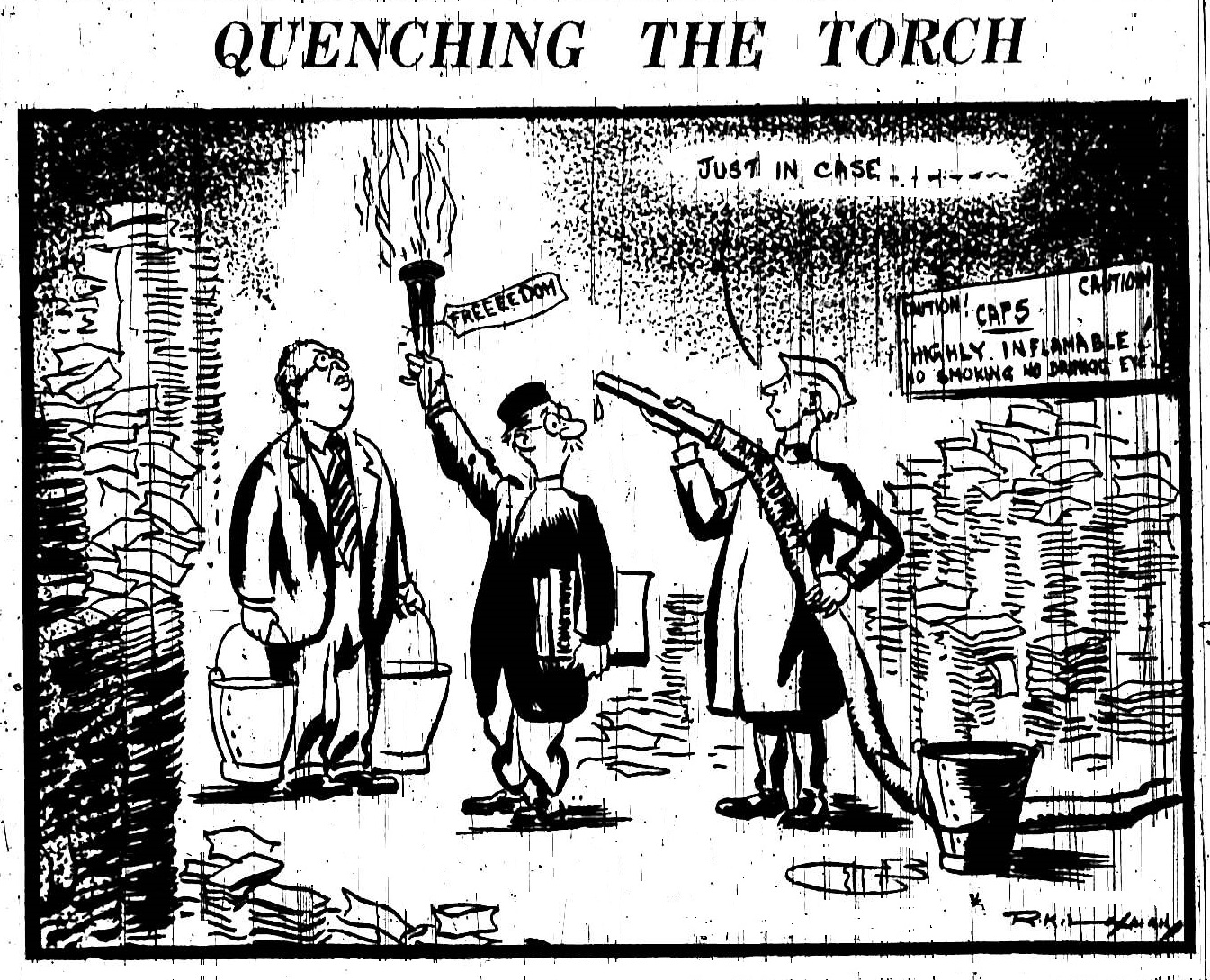

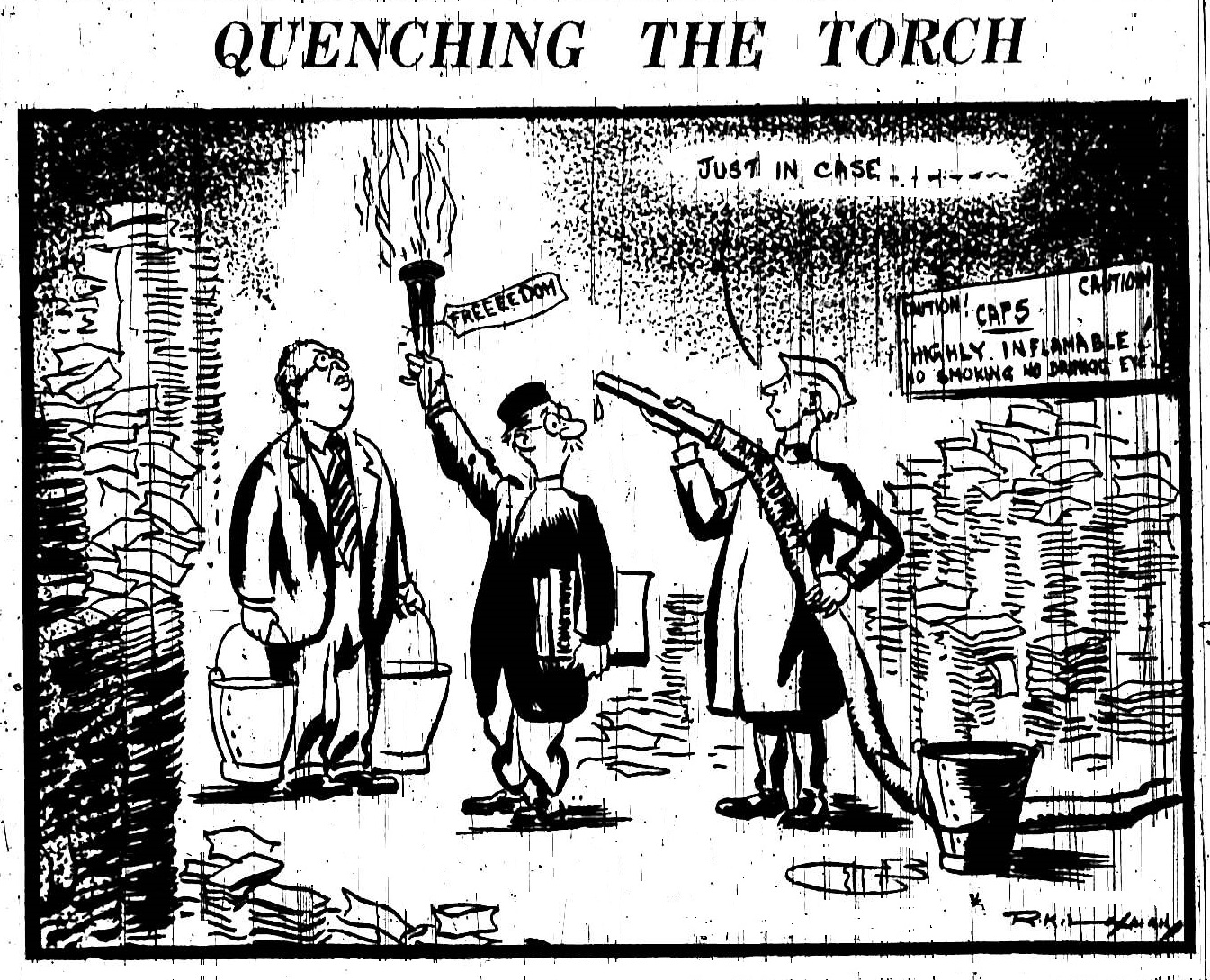

Quenching the torch

The Times of India, 19 May 1951, R.K. Laxman

The first amendment to the Constitution placed reasonable restrictions on freedom of speech. This came at a time when anti-Muslim and anti-Pakistan rhetoric was at a high pitch and communal violence had become rampant. Even under the British rule there was a distinct communal character to the restrictions placed on free speech. A landmark case was that of the publication of a book, Rangila Rasul, in 1927. That was a time when the Arya Samaj and the Muslims of Punjab were engaged in a malicious game of offending each other’s sensibilities. Rangila Rasul was a Samajist satire, exploring the sexual life of Prophet Mohammed in scandalous ways. This caused massive unrest in the state, leading to the arrest of the publisher of the piece Mahashe Rajpal. Because there was no provision in law to deal with offense to religious sentiments, he was let go. Upon his release, a young Muslim, Ilm-ud-Din, stabbed Rajpal to death. Ilm-ud-Din was executed for his crimes.

The violent events that had been caused by the book led the government to pass a new Hate Speech law which protected religious sentiments. The trend sustains.

Scratching the surface

Shown here the common man’s fire of freedom in an inflammable factory of Congress caps. Nehru aided by Ambedkar works to extinguish this flame. The tradition lives on.

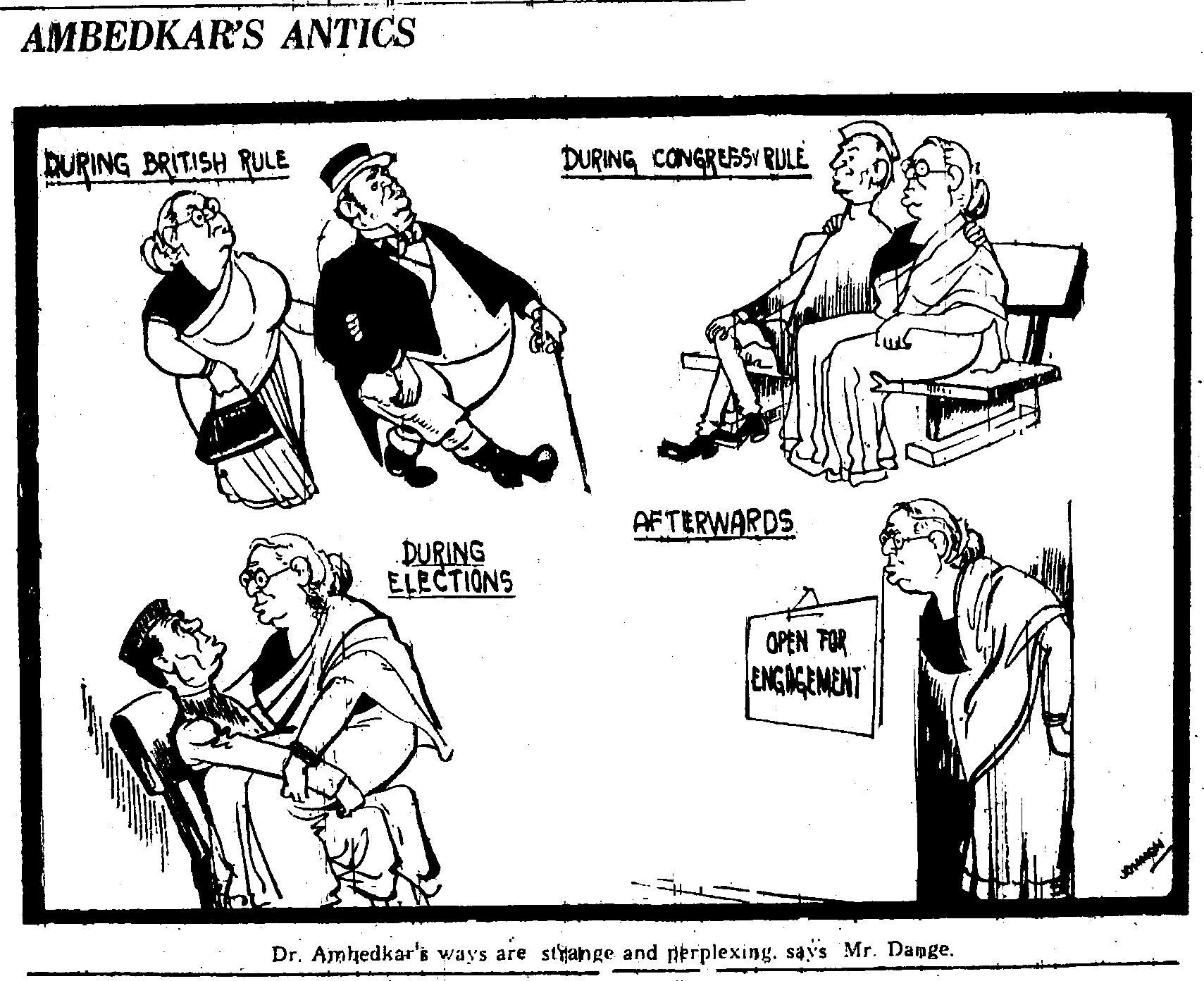

Ambedkar’s antics

Leader, 7 December 1951, Oommen

Caption – Dr. Ambedkar’s ways are strange and perplexing says Mr. Dange

The cartoon came off the back of the criticism lobbed against Ambedkar by the Communist Party of India leader, S.A. Dange. Addressing a mass rally held by the Left Front, he accused Ambedkar of a lack of convictions and principles. His loyalty was described as fickle for having sided with the British, the Congress and the Socialists at different points of time, after having denounced each camp in the past. Dange was one of India’s leading brahmanical communists, who led the charge of India’s early simplistic and dogmatic communist movements. His relation with Ambedkar had always been fractious. It was believed that the Depressed Class leader was dividing the working class by raising caste issues. This when factory workers unabashedly practised Untouchability, and the CPI complied with their demands of separate cooks and work areas. It is not a surprise that in 1975 Dange lent support to his son-in-law, Bani Deshpande’s book, The Universe of Vedanta, which drew parallels between Hindu philosophy and Marxism, nearly leading to his expulsion from the party. Influenced by Tilak in his early years, Dange’s casteism carried on through his communist life, when he often castigated the non-brahmin movement burgeoning in Maharashtra in his editorials in Socialist.

After exiting the Nehru cabinet, Ambedkar sought to ally himself with the Socialist Party. Asoka Mehta and Ambedkar ran on a common platform in Bombay, to act as the principal opposition to Congress. In the lead-up to these elections, to be held in 1952, Dange predictably spewed vitriol against Ambedkar. He exhorted the people to void their votes rather than casting them in favour of Ambedkar. Although, the CPI didn’t have a sizeable pull, their constituency was similar to the Ambedkar-Socialist camp, and they held sway in constituencies such as Girangaon, literally the ‘mill village’, which were key battlegrounds for Ambedkar. Eventually, Ambedkar (and the Socialists) lost the election, with 73,333 wasted votes cast in the constituency. Dange was dragged to the election tribunal by Ambedkar and Mehta, for unduly influencing the voters, but their appeal was dismissed.

Scratching the surface

No comments to report. There is nothing problematic going on in the image. Great use of freedom of expression by the cartoonist. Gratuitous sexism is a birthright.

These excerpts from No Laughing Matter: The Ambedkar Cartoons 1932 – 1956 have been carried with generous permission from Navayana Publishers. You can buy – No Laughing Matter by clicking on the book cover above.

Unnamati Syama Sundars’ childhood years in Vijayawada were spent leafing through the likes of Calvin and Hobbes, Dennis the Menace, Chacha Chaudhary, and Amar Chitra Katha. He is currently a doctoral researcher at JNU’s School of Arts and Aesthetics and researches the art featured in Chandmama, a popular Telugu children’s magazine founded in 1947. His Ambedkarite cartoons are well-known and regularly feature on roundtableindia.co.in.

Leave a Reply