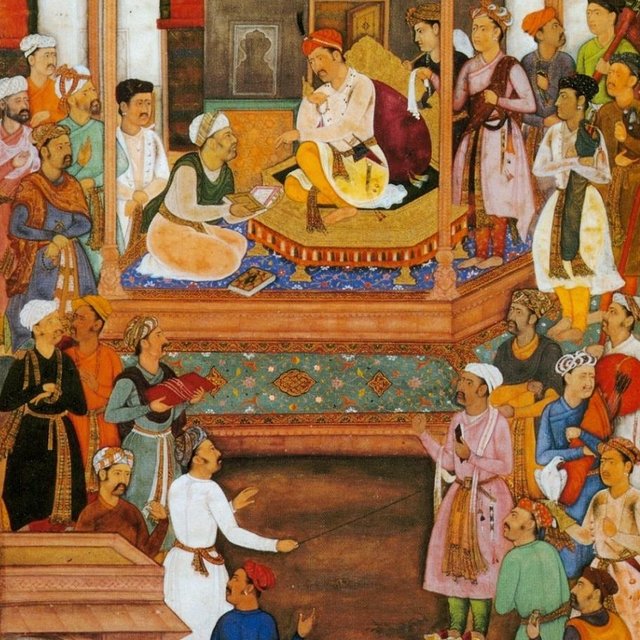

Illustration to the Akbarnama by Nar Singh, c. 1605

The year is 1575. Akbar has just returned to Fatehpur Sikri from Patna, and is brimming over with a zeal for reform. One of these is related to the nobility (implementing the administrative reforms). The other is connected with the clergy: establishing the Ibadat Khana for weekly theological debates (limited to Muslim theology, at that point). These reforms were to serve as pillars for Akbar’s newly envisioned state structure, where the legitimacy and authority of the state would flow from the monarch and no one else.

“This was, as many historians have argued, the logic and the genius of the mansabdari system,” Parvati Sharma writes in her book, Akbar of Hindustan. “But first, he would have to find the man to help him do it.”

In 1574, two men, poles apart from each other, had found their way to the court of Akbar due to their exceptional talent and, perhaps, destiny. “[W]e were… loaves out of the same oven,” wrote one of them, Abdul Qadir Badauni, the second ‘loaf’ being his “eternal nemesis” Abul Fazl.

Ali Anooshahr, in his article Mughal Historians and the Memories of the Islamic Conquest of India suggests a ‘liberal versus conservative’ polarity dividing the world views of the two men (though to see thus would be to apply today’s political lenses to a time when such politics may not have existed): “On the one hand is Abu al Fazl ‘Allami (d. 1602), the intimate of the emperor, praised by most modern scholars for his ‘rationalism’, ‘tolerance’, ‘complete absence of religious fanaticism’, and ‘secular’ vision… Opposite Abu al-Fazl is placed Abd al-Qadir Badauni (d. 1615)… censured, or at least noted, by moderns as a ‘fundamentalist’ mullah, a ‘narrow-minded’ Sunni, ‘rigid and orthodox’, ‘crabbed and bigoted’… ”

While we don’t have a record of Akbar’s first impression of either of them, Sharma’s reading of their accounts tells us that Badauni was the more experienced and elder of the two when they came to Akbar’s court. Abul Fazl, on the other hand, appears “innocent of the ways of the world. He… describes himself as a shy, bookish man, uninterested in the glamour of court life.”

In his paper The Life and Thought of ‘Abd Al-Qādir Badā’ūnī Rais Ahmad Khan writes that Badauni presented himself at Akbar’s court “through the good offices of Jalal Khan Qurchi, and Hakim ‘Ayn al-Mulk, a court physician”. From a reading of Badauni’s own account, Muntakhab ul Tawarikh, Khan gathers that Akbar welcomed his arrival at the court “as he was looking for some one to help break the power of the court ‘ulama”.

It is important to note that Akbar was still a devout Muslim at this time, preparing to establish an Ibadat Khana where he could be a part of Islamic theological debates. He had been involved in carrying out measures to eliminate “the power and influence of the court ‘ulama and balancing the different elements in the body politic of the Mughal empire” (Khan). The first steps in the direction of this policy, according to Khan, were his matrimonial alliance with the Rajputs (1562), the abolition of the pilgrim tax (1563), the abolition of the jizyah (1554) and the opening of the higher echelons of bureaucracy to Hindus. And, therefore, to break the constant tussle between the ‘ulama and the court, he saw Badauni “as a likely ally against the entrenched ‘ulama at the court” (Khan).

Abul Fazl, by contrast, was motivated by his father, Shaikh Mubarak, and his elder brother, Faizi (already in the service of Akbar), to appear for a job interview of sorts at Akbar’s court, in 1574.

If not for his shy nature, Fazl would very well have accompanied Akbar to Patna for his 1574 conquest, for he was invited by the shahinshah himself. But he refused, regretfully. In 1575, when Akbar returned to Fatehpur, Fazl was back at the court, writes Sharma, “Armed with excuses (he couldn’t have travelled without his father’s permission); flattery (he’d had visions of Akbar’s victory); and yet another essay on yet another set of verses from the Quran (of which Badauni observes cattily, ‘people said it was written by his father’).”

Akbar was keen on implementing the above-mentioned administrative and religious reforms, and now he had the man he needed, at his door. As Sharma writes, “Akbar saw him, recognized him! Thrilled, Abul Fazl rushed forward. The rest is history.”

Even though Fazl may have portrayed himself as a shy character “dragged into the material world”, it is necessary for a historian studying him to find other sources for who he was. Sharma, through her reading of Maathir-ul-Umara, tells us that its authors have described Fazl as a “gregarious, generous man”. “He kept a lavish table, for example,” the Maathir-ul-Umara reads. “With 22 seers (about 20 kg) of food served every day; in the first and last military expedition of his life, he had 1000 dishes cooked for every meal, mostly to be distributed … Every year, he would burn his books of account (to eliminate all debts, presumably) and give all his clothes to his staff.”

When we read Badauni, however, Fazl is accused of being the “flatterer beyond all bounds” that “set the world in flames” by destroying the ‘ulema. It was by such “time-serving qualities”, writes Badauni, that Fazl raced through the ranks, while “poor I! [Badauni]… could not manage to advance myself”. For Badauni’s career at court advanced at a very different, and disappointing, pace. He began looking for ways through which his regular presence at the court would not be required, since he wished to spend his time in literary pursuits.

Abul Fazl’s view of Badauni, however, may not have been as acidic. When Badauni overstayed his leave from court or absented himself for long periods without royal permission, writes Khan, “It was only through the good offices of Faizi, Abu’l-Fazl and Bakhshi Nizam al-Din and the generosity of Akbar that his grant was restored each time.”

“The trouble wasn’t that Badauni couldn’t escape his fate,” Sharma writes. “But that his talent wouldn’t let him escape it.” So appreciative was Akbar of this talent that he is supposed to have said, “[W]henever I give him anything to translate, he always writes what is pleasing to me, I do not wish that he should be separated from me.” But, no matter how well Badauni was paid at the court for his translation work, writes Sharma, “he only wished he would finish in two or three months and then die.”

In this excerpt, Parvati Sharma gives us insights into the personal and professional lives of the two historians: how they entered the court of Akbar, how they advanced their careers and literary pursuits and in what way they fitted in with the new reforms that Akbar was keen to introduce with them by his side. The excerpt also gives us a glimpse of the minds of these two scholars as they came to terms with Akbar’s Ibadat Khana, the theological debates that he was a part of, and his search for the truth. Unlike histories of the ‘renaissance’ or ‘enlightenment’ in Europe, Indian Mughal, medieval and even ancient histories (especially those that are more accessible) are more often than not focused on rulers and dynasties, overlooking the thinkers, scholars, artists, and even bureaucrats, responsible for stitching the fabric of an era. Having already carried an chapter on Akbar’s relationship with religion from Ira Mukhoty’s biography (do read if you haven’t), we felt that this excerpt, on the lives and times of two intellectuals in Akbar’s court, each with a different outlook towards nearly everything, might go some way in curing this imbalance.

‘Akbar, a king like Alexander, attained his every wish.’ — Abu’l Fazl, The History of Akbar, vol. 6

There was a new confidence in Akbar when he returned to Fatehpur from Patna. In the first few months of 1575, he did two things that would not only cement the foundations of his own reign, but create a blueprint for rule that would endure centuries after Akbar’s demise.

First, after years of hedging by his nobility, Akbar finally pushed through his administrative reforms – every bit of land in the realm would belong to the crown, there would be no more fiefs; and every bit of farmed land would be remeasured – not with the customary rope, but with bamboo rods, for greater accuracy. As for the fief-holders, they were mansabdars now, with ranks and responsibilities, for which they would be paid a salary. Thus, a man might hold a rank between 10 and 5000, the number indicating how many cavalrymen he was obliged to provide the emperor when called upon to do so, and his salary calculated on how much it would cost to maintain so many men and horses – and, of course, the mansabdar himself.

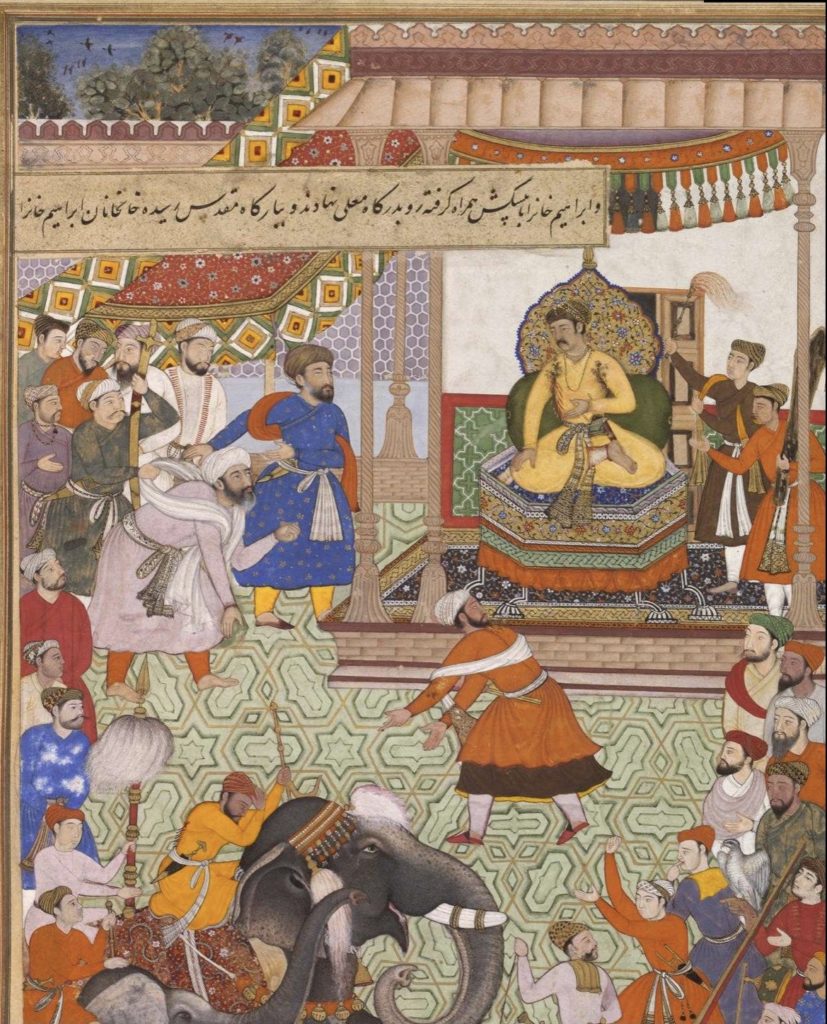

Second, Akbar began to host weekly theological debates in his newly built Ibadat Khana, a ‘house of worship’ to which the emperor invited clerics, scholars and believers of various (for the moment, only Muslim) sects for night-long debates of increasing acrimony.

It is hard to say which of the two decisions was more controversial, though both were born of ideas whose time had come.

It was now, writes the modern historian Ali Anooshahr, in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, that the Ottoman, Safavid and Mughal empires all moved from ‘the war band… to a bureaucratic absolutist “state”‘. Presumably, this was at least partly because there was only so far an empire could run on shields full of hidden treasure shared between warlords. It also indicated, however, a new focus on the monarch of this evolving state as the source of its legitimacy and authority. This was, as many historians have argued, the logic and the genius of the mansabdari system. Warlords like the Uzbeks or the Mirzas drew sustenance from the strength of their own arms and that of their clans; a mansabdar owed his salary, his authority, and therefore his loyalty, to the shahinshah.

It was now, writes the modern historian Ali Anooshahr, in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, that the Ottoman, Safavid and Mughal empires all moved from ‘the war band… to a bureaucratic absolutist “state”‘. Presumably, this was at least partly because there was only so far an empire could run on shields full of hidden treasure shared between warlords. It also indicated, however, a new focus on the monarch of this evolving state as the source of its legitimacy and authority. This was, as many historians have argued, the logic and the genius of the mansabdari system. Warlords like the Uzbeks or the Mirzas drew sustenance from the strength of their own arms and that of their clans; a mansabdar owed his salary, his authority, and therefore his loyalty, to the shahinshah.

It would be a long while, of course, before these newly minted mansabdars – and particularly the higher-ranking noblemen, ‘amirs’, among them – came to accept Akbar’s new design. Resentments would fester, battles would erupt – the turmoil would be such that even Muhammad Hakim, Akbar’s half brother, safely retreated to Kabul these past many years, would sniff another opportunity in Hindustan.

If Akbar anticipated any of this in 1575, when he announced his reforms, he did not let it worry him unduly. In fact, having decided to bring his nobility to heel and their revenue into his own treasury, Akbar opened up a second front, too – he would also take on his clergy.

If the shahinshah was the symbolic core of the Mughal bureaucracy as it was now emerging, Akbar also occupied the literal centre of his Ibadat Khana. The building does not stand any longer, but the descriptions are clear. It was a large hall with four wings, each assigned to a particular group of men: amirs, philosophers, sayyids and Sufis. Akbar’s own seat was at the very centre of the hall, from where he watched them all, and ‘tested them company by company’ – until he formulated his own creed.

It was also at this time that the man whom you might call Akbar’s high priest re-entered his life. At his first shy meeting with the emperor, Abul Fazl had been invited to travel east with him. The young man had made his excuses. For all his claims about being invaded by love for the shahinshah, the reclusive scholar may have been quietly horrified at the idea of travelling so far away from home with a boisterous military camp. Abul Fazl had hurried back to his father’s house, while Akbar ‘gave rein to his river-drinking crocodile’ and sailed away to Patna.

Afterwards, Abul Fazl may have regretted not accepting the emperor’s invitation; or perhaps it was his family that was dismayed by such a wilfully missed opportunity. At any rate, he was back at court: armed with excuses (he couldn’t have travelled without his father’s permission); flattery (he’d had visions of Akbar’s victory); and yet another essay on yet another set of verses from the Quran (of which Badauni observes cattily, ‘people said it was written by his father’).

Walking through the grand mosque in Fatehpur, Abul Fazl saw the emperor arrive, in the distance. Not daring to approach, he bowed from where he stood. And…could it be? Akbar saw him, recognized him! Thrilled, Abul Fazl rushed forward.

The rest is history.

Walking through the grand mosque in Fatehpur, Abul Fazl saw the emperor arrive, in the distance. Not daring to approach, he bowed from where he stood. And…could it be? Akbar saw him, recognized him! Thrilled, Abul Fazl rushed forward. The rest is history.

***

More than once, in the Akbarnama, Abul Fazl portrays himself as a shy and lonely character dragged into the material world despite himself. When he arrived in Fatehpur for the second time, Abul Fazl says he had no friends. in the city, that ‘there was no kind person to console me’. Yet, he continues piteously, ‘[m]y youth would not allow me to ask for assistance’. What pulled him out of his shell was the all-powerful emperor, his near-divine muse. ‘What portion can a bewildered, headless and footless mote have in the beams of the world-lighting Sun? It can only be tossed about in the wind’, he wrote in his preface to the Akbarnama.

A miniature showing Abū’l Faẓl presenting the Akbarnāmā to Emperor Akbar (Wikimedia Commons)

Others saw Abul Fazl differently. The authors of the Maathir-ul-Umara, a who’s who of the Mughal nobility compiled in the eighteenth century, describe a gregarious, generous man. He kept a lavish table, for example, with 22 seers (about 20 kg) of food served every day; in the first and last military expedition of his life, he had 1000 dishes cooked for every meal, mostly to be distributed. Abul Fazl would never dismiss an employee, the Maathir-ul-Umara goes on, nor ever fine or otherwise punish anyone, no matter how poorly they performed. Every year, he would burn his books of account (to eliminate all debts, presumably) and give all his clothes to his staff. The reticent bookworm, if at all he ever existed, must have blossomed in the warmth of Akbar’s patronage.

But success does not guarantee popularity. Badauni’s pen is never so acidic as when he describes his ‘officious…openly faithless’, colleague, ‘continually studying the Emperor’s whims, a flatterer beyond all bounds’. It was by such ‘time-serving qualities’, writes Badauni, that Abul Fazl raced through the ranks, while – ‘poor I’! – Badauni ‘could not manage to advance myself’. Even Badauni suggests, however, that it wasn’t only the usual currying for favour and promotion that animated Abul Fazl. The young scholar came to court not so much to make his own fortune, but to destroy the ulema that had persecuted his family. ‘He is the man,’ writes Badauni, ‘that set the world in flames.”

But success does not guarantee popularity. Badauni’s pen is never so acidic as when he describes his ‘officious…openly faithless’, colleague, ‘continually studying the Emperor’s whims, a flatterer beyond all bounds’. It was by such ‘time-serving qualities’, writes Badauni, that Abul Fazl raced through the ranks, while – ‘poor I’! – Badauni ‘could not manage to advance myself’. Even Badauni suggests, however, that it wasn’t only the usual currying for favour and promotion that animated Abul Fazl. The young scholar came to court not so much to make his own fortune, but to destroy the ulema that had persecuted his family. ‘He is the man,’ writes Badauni, ‘that set the world in flames.”

Whether or not Abul Fazl really daydreamed of setting alight an old world order as he walked the streets of Fatehpur, clutching his essay and hoping to catch the emperor’s eye, there was a great speed, certainly, with which the court ulema lost favour after his appointment in Akbar’s service – the speed, one might say, of a vengeful blade.

***

The idea of Akbar’s rare, possibly unique vision of harmony between religious communities – sulh-i kul, or peace for all – is so deeply ingrained in the popular imagination that it has produced its own corollary, a fraught religious terrain ‘before and after Akbar’. Thus, for example, R.C. Majumdar has argued that, ‘With the sole exception of Akbar, who sought to conciliate the Hindus by removing some of the glaring evils to which they were subjected, almost all the other Mughul Emperors were notorious for their religious bigotry’.

The idea of such Akbarid exceptionalism is as logically and historically untenable, however, as the idea of any one nation out of all others having a manifest destiny. No man, let alone a society, can exist in absolute terms – least of all a man who lived as long and varied a life Akbar did. There was a ‘before Akbar’ to Akbar’s own self, in fact, as the emperor confessed quite cheerfully.

The idea of such Akbarid exceptionalism is as logically and historically untenable, however, as the idea of any one nation out of all others having a manifest destiny. No man, let alone a society, can exist in absolute terms – least of all a man who lived as long and varied a life Akbar did. There was a ‘before Akbar’ to Akbar’s own self, in fact, as the emperor confessed quite cheerfully.

One of the sections in Abul Fazl’s Ain-i-Akbari is a compendium of Akbar’s most quotable quotes titled, in translation, ‘The Happy Sayings of His Majesty’. If the title evokes an unfortunate vision of fixed smiles around North Korean dictators, the sayings themselves are often disarmingly frank. Thus, Akbar recalls the religious zeal of his youth with regret: ‘Formerly I persecuted men into conformity with my faith and deemed it Islam.’ With age and learning, he continues, ‘I was overwhelmed with shame’.

He was also overwhelmed, it seems, with a febrile yearning. In another of his Happy Sayings, Akbar sounds decidedly miserable: ‘Although I am the master of so vast a kingdom, and all the appliances of government are to my hand, yet since true greatness consists in doing the will of God, my mind is not at ease in this diversity of sects and creeds, and my heart is oppressed by this outward pomp of circumstance; with what satisfaction can I undertake the conquest of empire? How I wish for the coming of some pious man, who will resolve the distractions of my heart.’

A painting depicting the scenes of the Ibādat Khāna. (Wikipedia Commons)

A king’s duty was God’s will, after all; or, as Akbar put it, ‘Divine worship in monarchs consists in their justice and good administration’. But with multiplicity of gods in his realm, how was a ruler to know he wasn’t such a in thrall to the Devil by mistake?

Akbar returned from Bengal and became as obsessed with prayer as he had been with conquest. Badauni describes him sitting alone on a large flat stone of an old building’ near his palace, his head bent to his chest, absorbed in contemplation. Sometimes, he spent ‘whole nights in praising God… pronouncing Ya huwa and Ya hadi… full of reverence for Him, who is the true Giver”.

***

While Akbar sought after Truth, what of his subjects? It is hard to get a proper sense of religious feeling across the many diverse societies that comprised Akbar’s growing empire; what impact religion had, great or little, on people’s everyday lives. It is equally hard, however, to escape the sense that religion – whether as ritual or as a way of imagining a just world – was a quotidian and compelling force.

While Akbar sought after Truth, what of his subjects? It is hard to get a proper sense of religious feeling across the many diverse societies that comprised Akbar’s growing empire; what impact religion had, great or little, on people’s everyday lives. It is equally hard, however, to escape the sense that religion – whether as ritual or as a way of imagining a just world – was a quotidian and compelling force.

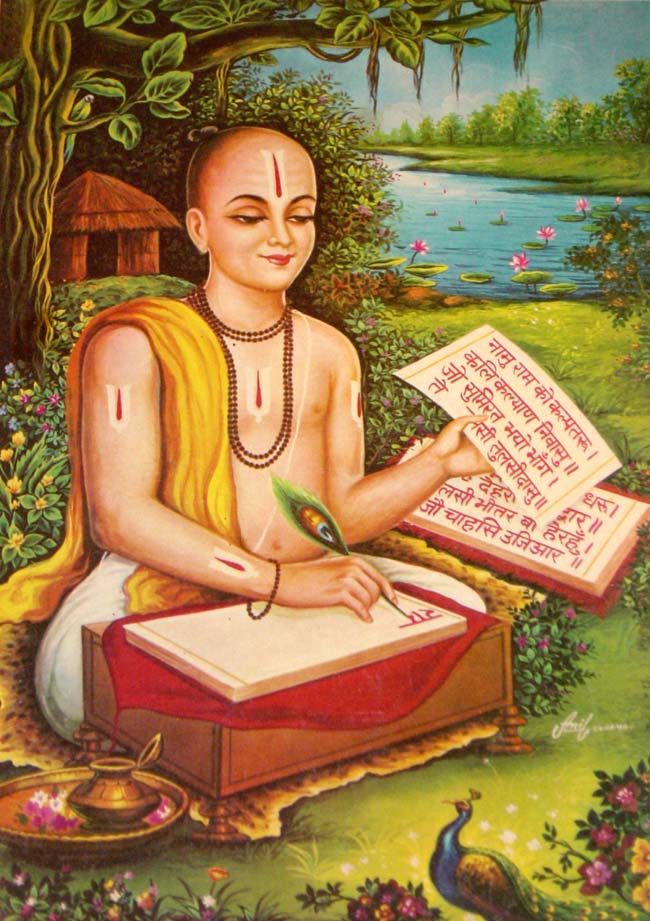

It was during the sixteenth century, for example, that Tulsidas wrote the Ramcharitmanas and Guru Arjan Dev compiled the Adi Granth -some indication of the sheer variety of ideas, religious and social, that were in ferment, even in competition, at the time. These two monumental texts both offered ideas and ideals of truth and justice that would not have agreed with each other in every point. Thus, for example, B.B. Majumdar describes how Tulsidas ‘states with evident regret that the Surdas now impart knowledge to the Brahmanas, take the sacred thread and accept reprehensible gifts… This was certainly a fling at the popularity of Ravidas the shoe-maker, Dharna the Jat, Sena the barber and other religious leaders belonging to non-Brahmana castes’, some of whom were prominent Bhakti saints. Sikhism, on the other hand, the tenets of which Guru Arjan Dev first compiled in the Adi Granth, was influenced by the Bhakti movement; indeed, the Adi Granth contains verses by several Bhakti saints. Evidently, this evolving faith ruffled some feathers, complaints about the Adi Granth seem to have reached Akbar, at which Guru Arjan Dev sent him the book. The emperor, having heard some excerpts, declared, ‘Excepting love and devotion to God I so far find neither praise nor blame of any one in this Granth. It is a volume worthy of reverence’.

Tulsidas composing his famous Avadhi Ramcharitmanas (Wikipedia Commons)

Poets, philosophers and saints might argue, emperors might adjudicate, but what of the everyday Hindustanis who practised what they preached? It might be almost impossible to imagine any of these lives were it not for the wonderful autobiography of a Jain trader and poet called Banarasidas. In a lucid, honest and often very funny account of his adventures (beautifully translated by Rohini Chowdhury), Banarasidas includes his struggles with ritual and faith. In his youth, writes Banarasi, he fell for a sanyasi’s get rich-quick scheme, and bought a mantra that he was to recite every day for a year, after which, every day, a gold coin would appear at his door for the rest of his life. For an entire year, every day,’ writes Banarasidas, ‘With firm and unwavering belief,/ In the solitude and secrecy of the privy / Banarasi, the blockhead, recited the mantra…’ A year later, he opened his front door. No immediate glitter caught his eye. Poor Banarasi ‘examined the ground carefully’- no doubt growing more annoyed with every desperate scrutiny of the soil and shadows. ‘He found no dinar anywhere.’

It was a blow, but it did not end Banarasi’s quest. The young man would go on to experiment with Saivism, then return to his own Jain faith, but never to find the spiritual satisfaction he sought. The performance of rituals no longer held any joy for him,’ writes the merchant of himself, ‘But he could not appreciate the spiritual aspects either. / Banarasi’s condition became similar to/That of a camel’s fart, which hangs between earth and air.’ Eventually, Banarasidas gave up on all forms of worship and ritual, veering full tilt into heresy instead, so much so that he would even eat the food left in offering to the gods.

So, it seems, a man could journey from superstition to scepticism as freely as Banarasidas travelled from Jaunpur to Agra for his trade. That is not to say, however, that religious belief imposed no constraints on how people were allowed to live.

So, it seems, a man could journey from superstition to scepticism as freely as Banarasidas travelled from Jaunpur to Agra for his trade. That is not to say, however, that religious belief imposed no constraints on how people were allowed to live.

Thus, Badauni tells the tragic tale of an inter-religious (and adulterous) love affair. Romance, it seems, was the otherwise sardonic Badauni’s Achilles heel – himself not above canoodling in a dargah, he couldn’t resist a good love story, whether between Ali Quli and that beautiful rake, Shahim Beg, or now, between Sayyid Musa and the beguiling Mohini.

Some five years before Akbar began his debates in the Ibadat Khana, at about the time that Akbar’s Rajput queen was pregnant with Salim, a young sayyid nobleman from Kalpi called Musa arrived in Agra to pay his respects to the increasingly powerful padishah. Musa was making his way through the city when he caught a glimpse of a beautiful face at a high window. It was Mohini he had seen; she was a goldsmith’s wife, and he was ensnared in ‘the lasso of her pure glance’.

Fortunately for his heart, less so for his future, Musa’s feelings were returned. The lovers knew they were treading dangerous ground and so, for two and a half years, they were ‘content with a glance now and then from afar’. But patience is not the strong suit of wildly beating hearts. One night, Musa took his life in his hands and broke into Mohini’s house, climbing up to her room ‘like a rope-dancer’ and finding his own home in her arms.

The next morning, Mohini left home with her lover, ‘despising fair fame and reputation’, writes Badauni with admiration,… as the moonlight with the moon’. Soon, however, as her relatives gathered in protest and Musa’s life came under threat, Mohini returned home. She told her family that she had been spirited away to an enchanted land. ‘The silly Hindus believed this beautiful deception,’ says Badauni, though evidently not without large grains of salt, for they kept Mohini ‘in a ring of iron serpents’ from now on, shut away ‘in an upper room’ under lock and key.

In the time-honoured manner of lovers separated from their beloveds, Musa went mad. Mohini, unable to bear the thought of her suitor’s grief, escaped once again and once again, the lovers were caught and parted. This time, the police was involved, and Musa was sent to jail where, from longing, he grew as ‘thin as a new moon’.

Again – a third time – the lovers tried. A man called Qazi Jamal, a Hindi poet possessed of a good horse and strong nerves, helped them. He carried Mohini away on his ‘charger, head-tossing like the… steed of Fate …wind-footed and prancing’, racing along the banks of the Yamuna with half of Agra watching.

Mohini’s relatives were chasing behind, and many of Agra’s citizens ‘who were spectators of the scene [were shouting] in front’- and yet, the young girl might have made her escape if the steed of fate had not caught its feet in the mud. Mohini threw herself off the horse and told the poet to escape – tell Musa I tried!

The news of this third failure broke the wretched Musa. He died. It would have to be, of course, that his bier passed by the goldsmith’s house. Standing at the very window, perhaps, from which she had once exchanged flirtatious glances with a stranger, Mohini watched the funeral procession. When Musa’s still form was just below, she threw herself down, breaking the chains that bound her in the process. They found her weeping at his grave.

What could the family do? They let her be, ‘forgave her delinquencies’. Mohini converted to Islam and died.

‘Forgive me!’ Badauni writes in conclusion. ‘The language of love carried the reins of my pen irresistibly out of… my control.’

What is one to make of this story, except, of course, that Musa and Mohini might have suffered no differently in the Agra of the twenty-first century? It was as they died in forbidden love that Akbar had his first son with his Hindu wife, but Badauni draws no contrast between the two facts. Perhaps there is no contrast to be drawn: an emperor’s bride was not of one faith or another, she was a queen. And yet, it is Badauni, too, who often cavils at the great influence that Akbar’s Hindu wives had on him – as, for example, in the case of the brahmin accused of blasphemy.

What is one to make of this story, except, of course, that Musa and Mohini might have suffered no differently in the Agra of the twenty-first century? It was as they died in forbidden love that Akbar had his first son with his Hindu wife, but Badauni draws no contrast between the two facts. Perhaps there is no contrast to be drawn: an emperor’s bride was not of one faith or another, she was a queen. And yet, it is Badauni, too, who often cavils at the great influence that Akbar’s Hindu wives had on him – as, for example, in the case of the brahmin accused of blasphemy.

Both Badauni and Abul Fazl are personally involved in the story, so it must have occurred after Akbar’s return from Bengal, when both men were in his employ. Here is what happened.

A qazi, or judge, in Mathura, who had been collecting building material for a mosque, accused a brahmin of taking some of it and using it to build a temple instead. In the argument that followed, the brahmin poured salt on the injury caused by his alleged theft by abusing the Prophet Muhammad – a sacrilege confirmed by Abul Fazl, who was sent to Mathura to investigate.

The case came before Shaikh Abdun Nabi.

Abdun Nabi had joined Makhdum-ul-Mulk in persecuting Abul Fazl’s family, and had risen to the highest judicial rank in the realm. He was Akbar’s sadr- his chief justice – who not only adjudicated legal matters but also distributed pensions and grants of land to holy men. Akbar was both fond and respectful of his sadr. Badauni describes the emperor rising ‘to adjust the Shaikh’s slippers when he took his leave’; and Akbar sent his eldest son, Salim, to Abdun Nabi’s school. The shaikh had great influence on the emperor, and great power, too, but he wasn’t very popular.

It may not be surprising if Abul Fazl, knowing how Abdun Nabi and men like him had conspired against his father, is less than admiring of the sadr.

Describing how Akbar gave Abdun Nabi his high post, Abul Fazl mutters the aside that the shaikh ‘decked out his shop with hypocrisy’. Badauni, too, has little good to say about the judge – partly because of how Abdun Nabi dealt with his powers over grants of land to religious men.

Central And Provincial Administrative Departments Under Akbar

It began well enough, writes Badauni, being dependent himself on such charitable madad-ma’ash grants and always appreciative of generosity – but things were soon ‘reversed’. As he would do with agricultural land, Akbar ordered a comprehensive reappraisal of all madad-ma’ash grants in his realm, putting the fate of countless men in Abdun Nabi’s hands. The shaikh did not take to this exponential increase in his powers with humility. Badauni describes him surrounded by petitioners, many of whom had already had to bribe his clerk, ‘or make presents to his chamberlains, doorkeepers, and sweepers’. Even then, it was difficult to get your voice heard, and imperative to beg. Some even died in the heat of the throng; while Abdun Nabi sat unconcerned on his ‘throne of pride’, sometimes washing his hands and feet, and making sure to splash the dirty water on the head and face and garments’ of the men around him – many of whom were powerful chiefs but, having come to plead a case, ‘bore all this, and condescended to fawn on him, and flatter and toady him to his heart’s content’.

Akbar didn’t seem to notice. No other emperor, writes Badauni, had ever given such ‘absolute power’ to his sadr. The blaspheming brahmin of Mathura would change all that.

The brahmin’s guilt was undisputed, it seems; it was his punishment that divided the court. Some favoured death; others suggested a less drastic penalty, such as public exposure and fine’; while a third party, ‘the ladies of the royal household’, pressed the emperor to release the man. From ‘regard to the Shaikh’, writes Badauni, ‘the King would not give his consent’. The case dragged on until Shaikh Abdun Nabi came to Akbar and asked for leave to execute the culprit. Akbar seems to have given him the same excuse he gave his queens. It was the sadr, he said, who was ‘responsible for carrying into execution the sentence of the law’- why had he come to Akbar?

Perhaps Abdun Nabi was so used to the emperor’s esteem that he mistook his indecision for deference. The brahmin was killed. And Akbar was furious.

As Badauni tells it, the ‘ladies within and the Hindus without’ stirred the pot of Akbar’s fury, until the emperor summoned a meeting of scholars, jurists and divines around the great tank at Fatehpur, the Anup Talao. Badauni was amongst them, and was eventually ordered to speak. ‘When ninety and nine opinions are in favour of a sentence of death,’ Akbar asked him, and a hundredth in favour of acquittal, do you think it right that the muftis should act upon the latter. What is your opinion?’

As Badauni tells it, the ‘ladies within and the Hindus without’ stirred the pot of Akbar’s fury, until the emperor summoned a meeting of scholars, jurists and divines around the great tank at Fatehpur, the Anup Talao. Badauni was amongst them, and was eventually ordered to speak. ‘When ninety and nine opinions are in favour of a sentence of death,’ Akbar asked him, and a hundredth in favour of acquittal, do you think it right that the muftis should act upon the latter. What is your opinion?’

Badauni replied that the law advised against punishment ‘where there was any doubt’. He added, however, that Abdun Nabi may have had compelling reasons to act as he did. Did he do it, perhaps, for the sake of expediency?

If Badauni was trying to strike a balance that would offend nobody, he did not please Akbar. The emperor’s ‘hair stood on end’, writes Badauni, ‘like that of a roused lion’. People around him whispered for Badauni to shut up. Then, Akbar himself looked at him and said, ‘You are not at all right’. Badauni bowed low and stepped back, silently vowing never to attend such meetings again.

Akbar’s fury did not have any immediate consequence on Abdun Nabi’s career. Perhaps the shaikh brushed it from his mind, telling himself that Akbar would soon find a conquest to distract him. But Akbar did not forget, and if he thought of marching into new territory, it was that of his clergy.

This excerpt has been carried courtesy the permission of Juggernaut. You can buy Akbar of Hindustan here.

Parvati Sharma’s debut The Dead Camel and Other Stories of Love earned her a cult following for its depictions of love and sexuality in urban India, and its “lightness [and] lucidity”. She has also written a novella, Close to Home, and two books for children, The Story of Babur and Rattu & Poorie’s Adventures in History: 1857. Her earlier biography, Jahangir: An Intimate Portrait of a Great Mughal (Juggernaut, 2018), was acclaimed as an “audacious, conversational history… [that] stands out”, and for its “psychologically penetrating portrayal”. Sharma lives in New Delhi, where she has studied English literature and Indian history, and worked as a travel writer, editor and journalist.

| 2500 BC - Present | |

|

2500 BC - Present |

| Tribal History: Looking for the Origins of the Kodavas | |

| 2200 BC to 600 AD | |

|

2200 BC to 600 AD |

| War, Political Violence and Rebellion in Ancient India | |

| 400 BC to 1001 AD | |

|

400 BC to 1001 AD |

| The Dissent of the ‘Nastika’ in Early India | |

| 600CE-1200CE | |

|

600CE-1200CE |

| The Other Side of the Vindhyas: An Alternative History of Power | |

| c. 700 - 1400 AD | |

|

c. 700 - 1400 AD |

| A Historian Recommends: Representing the ‘Other’ in Indian History | |

| c. 800 - 900 CE | |

|

c. 800 - 900 CE |

| ‘Drape me in his scent’: Female Sexuality and Devotion in Andal, the Goddess | |

| 1192 | |

|

1192 |

| Sufi Silsilahs: The Mystic Orders in India | |

| 1200 - 1850 | |

|

1200 - 1850 |

| Temples, deities, and the law. | |

| c. 1500 - 1600 AD | |

|

c. 1500 - 1600 AD |

| A Historian Recommends: Religion in Mughal India | |

| 1200-2020 | |

|

1200-2020 |

| Policing Untouchables and Producing Tamasha in Maharashtra | |

| 1530-1858 | |

|

1530-1858 |

| Rajputs, Mughals and the Handguns of Hindustan | |

| 1575 | |

|

1575 |

| Abdul Qadir Badauni & Abul Fazl: Two Mughal Intellectuals in King Akbar‘s Court | |

| 1579 | |

|

1579 |

| Padshah-i Islam | |

| 1550-1800 | |

|

1550-1800 |

| Who are the Bengal Muslims? : Conversion and Islamisation in Bengal | |

| c. 1600 CE-1900 CE | |

|

c. 1600 CE-1900 CE |

| The Birth of a Community: UP’s Ghazi Miyan and Narratives of ‘Conquest’ | |

| 1553 - 1900 | |

|

1553 - 1900 |

| What Happened to ‘Hindustan’? | |

| 1630-1680 | |

|

1630-1680 |

| Shivaji: Hindutva Icon or Secular Nationalist? | |

| 1630 -1680 | |

|

1630 -1680 |

| Shivaji: His Legacy & His Times | |

| c. 1724 – 1857 A.D. | |

|

c. 1724 – 1857 A.D. |

| Bahu Begum and the Gendered Struggle for Power | |

| 1818 - Present | |

|

1818 - Present |

| The Contesting Memories of Bhima-Koregaon | |

| 1831 | |

|

1831 |

| The Derozians’ India | |

| 1855 | |

|

1855 |

| Ayodhya 1855 | |

| 1856 | |

|

1856 |

| “Worshipping the dead is not an auspicious thing” — Ghalib | |

| 1857 | |

|

1857 |

| A Subaltern speaks: Dalit women’s counter-history of 1857 | |

| 1858 - 1976 | |

|

1858 - 1976 |

| Lifestyle as Resistance: The Curious Case of the Courtesans of Lucknow | |

| 1883 - 1894 | |

|

1883 - 1894 |

| The Sea Voyage Question: A Nineteenth century Debate | |

| 1887 | |

|

1887 |

| The Great Debaters: Tilak Vs. Agarkar | |

| 1893-1946 | |

|

1893-1946 |

| A Historian Recommends: Gandhi Vs. Caste | |

| 1897 | |

|

1897 |

| Queen Empress vs. Bal Gangadhar Tilak: An Autopsy | |

| 1913 - 1916 Modern Review | |

|

1913 - 1916 |

| A Young Ambedkar in New York | |

| 1916 | |

|

1916 |

| A Rare Account of World War I by an Indian Soldier | |

| 1917 | |

|

1917 |

| On Nationalism, by Tagore | |

| 1918 - 1919 | |

|

1918 - 1919 |

| What Happened to the Virus That Caused the World’s Deadliest Pandemic? | |

| 1920 - 1947 | |

|

1920 - 1947 |

| How One Should Celebrate Diwali, According to Gandhi | |

| 1921 | |

|

1921 |

| Great Debates: Tagore Vs. Gandhi (1921) | |

| 1921 - 2015 | |

|

1921 - 2015 |

| A History of Caste Politics and Elections in Bihar | |

| 1915-1921 | |

|

1915-1921 |

| The Satirical Genius of Gaganendranath Tagore | |

| 1924-1937 | |

|

1924-1937 |

| What were Gandhi’s Views on Religious Conversion? | |

| 1900-1950 | |

|

1900-1950 |

| Gazing at the Woman’s Body: Historicising Lust and Lechery in a Patriarchal Society | |

| 1925, 1926 | |

|

1925, 1926 |

| Great Debates: Tagore vs Gandhi (1925-1926) | |

| 1928 | |

|

1928 |

| Bhagat Singh’s dilemma: Nehru or Bose? | |

| 1930 Modern Review | |

|

1930 |

| The Modern Review Special: On the Nature of Reality | |

| 1932 | |

|

1932 |

| Caste, Gandhi and the Man Beside Gandhi | |

| 1933 - 1991 | |

|

1933 - 1991 |

| Raghubir Sinh: The Prince Who Would Be Historian | |

| 1935 | |

|

1935 |

| A Historian Recommends: SA Khan’s Timeless Presidential Address | |

| 1865-1928 | |

|

1865-1928 |

| Understanding Lajpat Rai’s Hindu Politics and Secularism | |

| 1935 Modern Review | |

|

1935 |

| The Modern Review Special: The Mind of a Judge | |

| 1936 Modern Review | |

|

1936 |

| The Modern Review Special: When Netaji Subhas Bose Was Wrongfully Detained for ‘Terrorism’ | |

| 1936 | |

|

1936 |

| Annihilation of Caste: Part 1 | |

| 1936 Modern Review | |

|

1936 |

| The Modern Review Special: An Indian MP in the British Parliament | |

| 1936 | |

|

1936 |

| Annihilation of Caste: Part 2 | |

| 1936 | |

|

1936 |

| A Reflection of His Age: Munshi Premchand on the True Purpose of Literature | |

| 1936 Modern Review | |

|

1936 |

| The Modern Review Special: The Defeat of a Dalit Candidate in a 1936 Municipal Election | |

| 1937 Modern Review | |

|

1937 |

| The Modern Review Special: Rashtrapati | |

| 1938 | |

|

1938 |

| Great Debates: Nehru Vs. Jinnah (1938) | |

| 1942 Modern Review | |

|

1942 |

| IHC Uncovers: A Parallel Government In British India (Part 1) | |

| 1943-1945 | |

|

1943-1945 |

| Origin Of The Azad Hind Fauj | |

| 1942-1945 | |

|

1942-1945 |

| IHC Uncovers: A Parallel Government in British India (Part 2) | |

| 1946 | |

|

1946 |

| Our Last War of Independence: The Royal Indian Navy Mutiny of 1946 | |

| 1946 | |

|

1946 |

| An Artist’s Account of the Tebhaga Movement in Pictures And Prose | |

| 1946 – 1947 | |

|

1946 – 1947 |

| “The Most Democratic People on Earth” : An Adivasi Voice in the Constituent Assembly | |

| 1946-1947 | |

|

1946-1947 |

| VP Menon and the Birth of Independent India | |

| 1916 - 1947 | |

|

1916 - 1947 |

| 8 @ 75: 8 Speeches Independent Indians Must Read | |

| 1947-1951 | |

|

1947-1951 |

| Ambedkar Cartoons: The Joke’s On Us | |

| 1948 | |

|

1948 |

| “My Father, Do Not Rest” | |

| 1940-1960 | |

|

1940-1960 |

| Integration Myth: A Silenced History of Hyderabad | |

| 1948 | |

|

1948 |

| The Assassination of a Mahatma, the Princely States and the ‘Hindu’ Nation | |

| 1949 | |

|

1949 |

| Ambedkar warns against India becoming a ‘Democracy in Form, Dictatorship in Fact’ | |

| 1950 | |

|

1950 |

| Illustrations from the constitution | |

| 1951 | |

|

1951 |

| How the First Amendment to the Indian Constitution Circumscribed Our Freedoms & How it was Passed | |

| 1967 | |

|

1967 |

| Once Upon A Time In Naxalbari | |

| 1970 | |

|

1970 |

| R.C. Majumdar on Shortcomings in Indian Historiography | |

| 1973 - 1993 | |

|

1973 - 1993 |

| Balasaheb Deoras: Kingmaker of the Sangh | |

| 1975 | |

|

1975 |

| The Emergency Package: Shadow Power | |

| 1975 | |

|

1975 |

| The Emergency Package: The Prehistory of Turkman Gate – Population Control | |

| 1977 – 2011 | |

|

1977 – 2011 |

| Power is an Unforgiving Mistress: Lessons from the Decline of the Left in Bengal | |

| 1984 | |

|

1984 |

| Mrs Gandhi’s Final Folly: Operation Blue Star | |

| 1916-2004 | |

|

1916-2004 |

| Amjad Ali Khan on M.S. Subbulakshmi: “A Glorious Chapter for Indian Classical Music” | |

| 2008 | |

|

2008 |

| Whose History Textbook Is It Anyway? | |

| 2006 - 2009 | |

|

2006 - 2009 |

| Singur-Nandigram-Lalgarh: Movements that Remade Mamata Banerjee | |

| 2020 | |

|

2020 |

| The Indo-China Conflict: 10 Books We Need To Read | |

| 2021 | |

|

2021 |

| Singing/Writing Liberation: Dalit Women’s Narratives | |

Leave a Reply